Loosely inspired by the story of Anna Anderson, Anastasia is a lush romantic period-piece which saw Ingrid Bergman return to Hollywood. Her return was so welcomed and her trespasses so forgiven that Hollywood ended up giving her an Oscar as a form of kiss-and-makeup. (My personal choice would have been Deborah Kerr in The King and I, but Bergman does solid and admirable work here.)

Bergman’s transformation from suicidal amnesiac to glamorous princess is believable thanks to her tremendous gifts as an actress. Her lustrous appearance is enough to convince us that she is royalty in pauper’s clothing. And Yul Brynner and Helen Hayes give her great supporting work. Hayes’ performance as the Dowager Empress is particularly affecting for the amount of depth, sorrow and skepticism she brings to the role. Brynner’s is more of a straight-man to the emotional fireworks given off by the female co-stars, but he equips himself well and possessed a commanding, imperial presence on-screen.

While Anastasia may look great and provide a kind of literate and sophisticated studio package that rarely gets made anymore, it’s also severely lacking in exciting or interesting images. Anatole Litvak has a beautiful canvas to work with in Bergman’s face and the costuming and production design, but he prefers to just point-and-shoot in a manner that makes the stage-origins of the piece highly obvious. There’s no excitement or sweeping romanticism to the look of the film. This film needed a George Cukor or Vincente Minnelli to liven up the look and feel of the whole enterprise. Litvak did better camera work in City for Conquest, which has its problems, but proves that he could be a great visualist when he wanted to, but for some reason with Anastasia he decided that filming it like a play was a decent enough choice.

The other major obstacle to getting through Anastasia is that the script has clearly decided that this amnesic woman is in fact the long thought dead princess, yet it insists on trying to present a mystery over her true identity. Too often Bergman’s character reminisces on tiny details that no one could learn from a history book, yet we’re still supposed to believe right up until the very last frame that she may not in fact be the princess. If the filmmakers had wanted to present this as more of a mystery it would’ve been better to create a larger sense of doubt in the viewer’s mind. Once every character becomes remotely convinced that she may be the genuine article any sense of doubt is shattered.

It’s always dubious to look to Hollywood for accurate history and Anastasia makes no pretense to even be remotely realistic, looking instead to craft a well-structured and slick romantic fable out of its various parts. For the most part it works thanks to Bergman, Brynner and Hayes delivering solid performances, even if the film as a whole is less than great. It’s certainly entertaining and has enough going for it to make it worth a look. How essential it is seems highly debatable, yet it has a highly fascinating backstory. One that may even be better than the actual film it produced.

Anastasia

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 9 April 2013 05:58

(A review of Anastasia)

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 9 April 2013 05:58

(A review of Anastasia) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

How to Steal a Million

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 9 April 2013 05:58

(A review of How to Steal a Million)

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 9 April 2013 05:58

(A review of How to Steal a Million)It may not have turned out to be a great movie, but How to Steal a Million is a good example of a film that could use a little bit of trimming around the middle. Namely in the sub-plot with Eli Wallach, which doesn’t seem of much use to the main thrust of the plot despite a last minute surprise reveal, could have been removed and a simple bit of dialog used in place to smooth over the story. Exercising this B story wouldn’t have made Million a masterpiece of the romantic comedy/crime-caper films of the 60s, but it would’ve improved it tremendously.

None of this is to say that Million is a bad film, far from it. It’s an enjoyable light-weight romp with Audrey Hepburn and Peter O’Toole. Their presence and gifts for this kind of acting makes it engrossing and highly watchable. I’d hesitate to call it cinematic junk food since that term sounds so damn harsh, it’s more like cinematic chocolate pieces. Bite-sized and sweet, it’s at its best when it allows its story to go on auto-pilot and observes the chemistry and romantic back-and-forth the leads provide. It may not rank up there with Charade, To Catch a Thief or Arabesque, but How to Steal a Million is utterly charming. And, really, who needs a great story when you have Peter O’Toole being elegant and suave, Audrey Hepburn being luminous and wrapped in Givenchy, and a script that does provide for some snappy banter and funny situations (even if it its problematic).

None of this is to say that Million is a bad film, far from it. It’s an enjoyable light-weight romp with Audrey Hepburn and Peter O’Toole. Their presence and gifts for this kind of acting makes it engrossing and highly watchable. I’d hesitate to call it cinematic junk food since that term sounds so damn harsh, it’s more like cinematic chocolate pieces. Bite-sized and sweet, it’s at its best when it allows its story to go on auto-pilot and observes the chemistry and romantic back-and-forth the leads provide. It may not rank up there with Charade, To Catch a Thief or Arabesque, but How to Steal a Million is utterly charming. And, really, who needs a great story when you have Peter O’Toole being elegant and suave, Audrey Hepburn being luminous and wrapped in Givenchy, and a script that does provide for some snappy banter and funny situations (even if it its problematic).

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Lawrence of Arabia

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 9 April 2013 05:58

(A review of Lawrence of Arabia)

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 9 April 2013 05:58

(A review of Lawrence of Arabia)Sometimes a film, and its production, is the stuff of myth, legend and that which dreams are made of. Lawrence of Arabia is a hallucinatory dream, sometimes filled to the brim with wonderment and romanticism, and just as quickly turning in a nightmarish hell from which there is no true escape. It’s the kind of grand movie-making that not only entertains but reaches a level of artistry that is impossible to deny or top.

It’s easy to try and quantify or classify a movie into simple genres and easily digestible identifiers like biographical film or action-adventure story, but Lawrence contains those elements while simultaneously rejecting those simple classifications. Entire sequences go on in real-time in the vast emptiness of the desert. The effect is simple: Lawrence uses the desert as a giant canvas to paint an impressionistic portrait of T.E. Lawrence in all of his grandeur, madness and folly.

Less concerned with strict narrative propulsion, Lawrence prefers to wrap us up in an emotional and sensory experience. And much of the credit for the success of the film rests on David Lean’s mesmerizing visual grammar and Peter O’Toole’s head-first abandonment in crafting the titular role. O’Toole’s role may even be trickier since he is rarely off-screen and frequently the subject of numerous, invasive close-ups which he has to hold for prolonged periods of time.

In addition to having to hold our attention while doing relatively little besides reacting in real-time to figures crossing the desert or subtly sign-posting his descent in madness and disenfranchisement, O’Toole’s physical commitment to the role offers up a great backstory. According to him he spent two years obsessing over the role, sprained both his ankles, was knocked unconscious twice and dislocated his spine. But his obsessiveness with the role shows through in every moment, and it is a grandly magnificent performance. This is the kind of acting which appears seamless and can give a movie a magical spark.

O’Toole may not be conventionally handsome, after spending nearly four hours studying his face in various expressions, lighting schemes and makeups, what we’re transfixed by are his large eyes and sensual mouth, which is to say nothing of his roguish Irish charms. Would another actor have commanded our attention so completely in a scene where Lawrence, dressed in white sheik’s garments, prances around like a peacock for no one in particular in a sand dune? Or would another actor have been able to capture the fey, high-camp humor in sequences in which he poshly tells military brass to bugger off and sell it so well? It’s hard to say, but I have my doubts. Life, and the vast empty desert, doesn’t seem big enough to contain this complicated figure.

O’Toole’s renegade charm allows for us to buy into what he’s selling – a new Arabia in which the British and other outside forces will leave well enough alone. This element of the film seems even more prescient currently as the Western influence in the Middle East is one of the biggest hot button topics in our news cycle. Yet O’Toole isn’t acting in a vacuum, despite how it may sound. Lean regular Alec Guinness has a small role as a worldly Arabian prince who constantly questions Lawrence’s motives in uniting the various factions. Seeing Guinness in brown-face is disconcerting, a harsh reminder of a time when something like this was considered perfectly fine. His very Anglo looks and clipped upper British tones never successfully merge with the garments he’s wearing. Anthony Quinn, acting through a terribly fake and obvious prosthetic nose, gives one of his typically big and grandiose performances, more to do with guttural pronouncements and heavy posturing than emoting and nuance.

The most successful supporting performance is the one with the most complicated baggage. Omar Sharif is Lawrence’s long-time friend and supporter Ali, one of the first Arabian tribe leaders that he meets and gets on his side. Sharif is the stable and supportive center that Lawrence needs as he zips back and forth between determined charisma and insolent madness. Lawrence, it was widely believed, was a homosexual, and it doesn’t take much careful reading or looking beneath the surface to see the questionable element to their friendship. Sequences involving wordless interactions or Ali nursing Lawrence back to health feature a gentle, almost lover-like touch to them. This isn’t the only element that hints at Lawrence’s sexuality – his prancing in robes and taking in two street kids also point to it, along with his generally fey demeanor and bitchy wit – but they’re the strongest example of encoding in a time of strict censorship.

But when one remembers or thinks of Lawrence, one remembers the whole confounding experience. This is because of David Lean’s expert execution of big dramatic ideas with a poetic visual style. Everyone remembers the desert mirage slowly forming into a black spot and then into a man, and that scene alone would allow for the movie to make it on any number of greatest films of all-time lists, but it isn’t the only visual that lingers in the mind.

Lean’s expressive use of color transforms the deserts into searing white oceans whose stillness belie the dangers inherent within them. Or the way he uses a visual echo to show the transformation happening within his main character. When Lawrence first gets the white desert sheik robes, he prances around and pulls out his knife to stare at it in awe. And it is a wondrous work of art – the design work and craft that went in to it are terrific. His sense of play and adventure are evident. The stakes are low, his mission simple, this is all before madness has overtaken him and his cause. Later, after a bloody battle, Lawrence is seen again staring at this knife, but this time it is with horror and shock, and the gilded weapon is now covered in violently red and vivid blood.

In this film, and The Bridge on the River Kwai or the much quieter Summertime, Lean knows that film is a primarily visual medium. Words and dialog are helpful, but not always necessary to show the slow descents into madness, or the sweeping nature of romance. He allows his scenes to unfold in a slow, methodical way and expands the film’s scope by doing so. He truly was one of the greatest directors and visual artists to have graced the big screen, and Lawrence may be his grandest achievement. It’s not a simple or easily digestible work, but it practically defines the word epic through its emotional scope and bold storytelling methods.

It’s easy to try and quantify or classify a movie into simple genres and easily digestible identifiers like biographical film or action-adventure story, but Lawrence contains those elements while simultaneously rejecting those simple classifications. Entire sequences go on in real-time in the vast emptiness of the desert. The effect is simple: Lawrence uses the desert as a giant canvas to paint an impressionistic portrait of T.E. Lawrence in all of his grandeur, madness and folly.

Less concerned with strict narrative propulsion, Lawrence prefers to wrap us up in an emotional and sensory experience. And much of the credit for the success of the film rests on David Lean’s mesmerizing visual grammar and Peter O’Toole’s head-first abandonment in crafting the titular role. O’Toole’s role may even be trickier since he is rarely off-screen and frequently the subject of numerous, invasive close-ups which he has to hold for prolonged periods of time.

In addition to having to hold our attention while doing relatively little besides reacting in real-time to figures crossing the desert or subtly sign-posting his descent in madness and disenfranchisement, O’Toole’s physical commitment to the role offers up a great backstory. According to him he spent two years obsessing over the role, sprained both his ankles, was knocked unconscious twice and dislocated his spine. But his obsessiveness with the role shows through in every moment, and it is a grandly magnificent performance. This is the kind of acting which appears seamless and can give a movie a magical spark.

O’Toole may not be conventionally handsome, after spending nearly four hours studying his face in various expressions, lighting schemes and makeups, what we’re transfixed by are his large eyes and sensual mouth, which is to say nothing of his roguish Irish charms. Would another actor have commanded our attention so completely in a scene where Lawrence, dressed in white sheik’s garments, prances around like a peacock for no one in particular in a sand dune? Or would another actor have been able to capture the fey, high-camp humor in sequences in which he poshly tells military brass to bugger off and sell it so well? It’s hard to say, but I have my doubts. Life, and the vast empty desert, doesn’t seem big enough to contain this complicated figure.

O’Toole’s renegade charm allows for us to buy into what he’s selling – a new Arabia in which the British and other outside forces will leave well enough alone. This element of the film seems even more prescient currently as the Western influence in the Middle East is one of the biggest hot button topics in our news cycle. Yet O’Toole isn’t acting in a vacuum, despite how it may sound. Lean regular Alec Guinness has a small role as a worldly Arabian prince who constantly questions Lawrence’s motives in uniting the various factions. Seeing Guinness in brown-face is disconcerting, a harsh reminder of a time when something like this was considered perfectly fine. His very Anglo looks and clipped upper British tones never successfully merge with the garments he’s wearing. Anthony Quinn, acting through a terribly fake and obvious prosthetic nose, gives one of his typically big and grandiose performances, more to do with guttural pronouncements and heavy posturing than emoting and nuance.

The most successful supporting performance is the one with the most complicated baggage. Omar Sharif is Lawrence’s long-time friend and supporter Ali, one of the first Arabian tribe leaders that he meets and gets on his side. Sharif is the stable and supportive center that Lawrence needs as he zips back and forth between determined charisma and insolent madness. Lawrence, it was widely believed, was a homosexual, and it doesn’t take much careful reading or looking beneath the surface to see the questionable element to their friendship. Sequences involving wordless interactions or Ali nursing Lawrence back to health feature a gentle, almost lover-like touch to them. This isn’t the only element that hints at Lawrence’s sexuality – his prancing in robes and taking in two street kids also point to it, along with his generally fey demeanor and bitchy wit – but they’re the strongest example of encoding in a time of strict censorship.

But when one remembers or thinks of Lawrence, one remembers the whole confounding experience. This is because of David Lean’s expert execution of big dramatic ideas with a poetic visual style. Everyone remembers the desert mirage slowly forming into a black spot and then into a man, and that scene alone would allow for the movie to make it on any number of greatest films of all-time lists, but it isn’t the only visual that lingers in the mind.

Lean’s expressive use of color transforms the deserts into searing white oceans whose stillness belie the dangers inherent within them. Or the way he uses a visual echo to show the transformation happening within his main character. When Lawrence first gets the white desert sheik robes, he prances around and pulls out his knife to stare at it in awe. And it is a wondrous work of art – the design work and craft that went in to it are terrific. His sense of play and adventure are evident. The stakes are low, his mission simple, this is all before madness has overtaken him and his cause. Later, after a bloody battle, Lawrence is seen again staring at this knife, but this time it is with horror and shock, and the gilded weapon is now covered in violently red and vivid blood.

In this film, and The Bridge on the River Kwai or the much quieter Summertime, Lean knows that film is a primarily visual medium. Words and dialog are helpful, but not always necessary to show the slow descents into madness, or the sweeping nature of romance. He allows his scenes to unfold in a slow, methodical way and expands the film’s scope by doing so. He truly was one of the greatest directors and visual artists to have graced the big screen, and Lawrence may be his grandest achievement. It’s not a simple or easily digestible work, but it practically defines the word epic through its emotional scope and bold storytelling methods.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Spider-Man: The 1967 Series

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 26 March 2013 08:45

(A review of Spider-Man)

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 26 March 2013 08:45

(A review of Spider-Man)Sometimes saying that a show is high-camp is not a knock against it. Sometimes it’s the highest form of praise for something that may or may not be striving for it. I’m still not completely sold on the idea that Spider-Man was supposed to be a high-camp action-adventure show, but I couldn’t find any other way to watch it.

While it seems like the barest amount of time, effort, skill and money went in to making this show, it does provided some extremely pleasurable viewing experiences. It’s nice to see a superhero show embrace some of the more zany, corny and outlandish aspects of its source material and run with them. Even if it does end up providing stories and conflicts that are half-baked and resolutions are of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it variety. Why does Rhino (twice!) want to make a golden statue of himself? What purpose could this possibly provide? The show never bothers to explain, but it does lead me to my next point.

In the comics, and to a much larger extent the video games, have Spider-Man’s webshooters have the ability to alter the size, shape and density of his artificial webbing. Ok, so far not too outrageous, but this show stretches that limit to the breaking point, if not a few notches past it. His webbing is a glue-like substance one minute, capable of turning hard as rock the next, pliable, easily escapable by villains, and other times it stops them dead in its tracts. Here his webbing doesn’t bother with any sort of physics or logic, not even of the flimsy comic book variety!, but exists solely as a dues ex machina in order to reach the conclusion of the episode.

So, there’s the laziness on the writers’ part, but what about the animation? To say that the show was produced on the lower-end is a nice way to put it. This show isn’t so much animated as it is a bunch of paper dolls held up in front of backdrops with the most limited amount of animation grafted on to them. There is no web-design on Spider-Man’s outfit for the most part, and frequently only his bottom jaw is animated. There’s a certain charm to the crudeness that used to pass for Saturday morning entertainment, but it reaches its breaking point in the second season’s bottom half and the entirety of the third season.

Recycling sequences in animation is no great secret, it happens quite often. But this show has to set the standard for it. Why bother to animate a new episode at all when one can just redub a previous one and cut it and reassemble it in such a way that it gives the appearance of being both new and old at the same time. Three episodes in a row in season two recycle the same animation sequences. I don’t mean the web-slinging stuff, which is used constantly to do nothing more than eat up time, I mean an entire sequence from an episode that has to last at least five minutes or more. It involves an underground civilization and the monstrous looking creatures that inhabit it. I thought I had already watched this episode and that my Netflix account was being glitch-ridden. Not so as it turns out thanks to a quick search on Wikipedia.

The third season must have roughly 15% new animation as the bulk of it is sliced and diced old episodes. Once more, the exact same villain actually, levitates Manhattan above the rest of New York. Vulture tries to commandeer and destroy a military gadget. Mysterio plans revenge on Spider-Man, and this instance has totally abandoned his traditional costume despite wearing it earlier on in the show’s run. These episodes are particularly rough to look at since they seem to have been made from well-worn materials.

And I don’t know what’s up the rogues gallery, but Spider-Man has a wealth of unique, colorful and interesting characters to choose from. The first season uses many of the most famous and adds a few new ones, but the second season abandons all of them for science-fiction storylines involving mad scientists, underground creatures and Nordic gods. This bizarre territory has a certain undefinable charm to it. Superhero shows are rarely allowed to get so surreal, even down-right head trippy. Comparing the first season to the latter ones is, frankly, hilarious.

The first season seems to exist in a knowing, obviously corny universe. There are good guys and bad guys, and they must each do their part in the action-packed story that has little or no time for character development or emotional investment. The backgrounds are clean, bright metropolitan cityscapes that are as Americana as apple pie, baseball, and you know the rest. Ralph Bakshi took over the main creative reigns beginning with season two and decided to make the show look more expressionistic and atmospheric. Suddenly the night skies became strange burst of black, purple and blue colors. Rocket Robin Hood, a silly sci-fi adventure show, was in production at the same time, and much of what was created for that show was recycled for this one. This explains the surreal, strange turn the whole enterprise took after a while.

If I’ve sounded like I hated the show, I didn’t. It held a curious charm, something you can’t quite put your finger upon. It’s easy to see how this became an internet meme, the show practically does it to itself in numerous occasions. I’m still trying to figure out why every female character that Peter Parker meets is a redhead who barely a stunning resemblance to Mary Jane, even though they’re never actually her until one episode where she’s turned into Captain Stacy’s niece and looks like a ginger Gwen Stacy.

But this show did provide the first adaptation of Spider-Man’s origin, and remains highly faithful given the constraints of children’s television, and Paul Soles does provide a nice voice for the character. Soles is fairly iconic at this point as the voice of the elf Hermey in Rudolph, and at times I couldn’t shake that mental image, it didn’t help that Paul Kligman plays his boss in both shows. But the “Gee whiz! Aw shucks” sweetness of the show, (un)intentional humor, crude animation and forward-momentum of the plots did make it easy, frequently enjoyable to watch.

While it seems like the barest amount of time, effort, skill and money went in to making this show, it does provided some extremely pleasurable viewing experiences. It’s nice to see a superhero show embrace some of the more zany, corny and outlandish aspects of its source material and run with them. Even if it does end up providing stories and conflicts that are half-baked and resolutions are of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it variety. Why does Rhino (twice!) want to make a golden statue of himself? What purpose could this possibly provide? The show never bothers to explain, but it does lead me to my next point.

In the comics, and to a much larger extent the video games, have Spider-Man’s webshooters have the ability to alter the size, shape and density of his artificial webbing. Ok, so far not too outrageous, but this show stretches that limit to the breaking point, if not a few notches past it. His webbing is a glue-like substance one minute, capable of turning hard as rock the next, pliable, easily escapable by villains, and other times it stops them dead in its tracts. Here his webbing doesn’t bother with any sort of physics or logic, not even of the flimsy comic book variety!, but exists solely as a dues ex machina in order to reach the conclusion of the episode.

So, there’s the laziness on the writers’ part, but what about the animation? To say that the show was produced on the lower-end is a nice way to put it. This show isn’t so much animated as it is a bunch of paper dolls held up in front of backdrops with the most limited amount of animation grafted on to them. There is no web-design on Spider-Man’s outfit for the most part, and frequently only his bottom jaw is animated. There’s a certain charm to the crudeness that used to pass for Saturday morning entertainment, but it reaches its breaking point in the second season’s bottom half and the entirety of the third season.

Recycling sequences in animation is no great secret, it happens quite often. But this show has to set the standard for it. Why bother to animate a new episode at all when one can just redub a previous one and cut it and reassemble it in such a way that it gives the appearance of being both new and old at the same time. Three episodes in a row in season two recycle the same animation sequences. I don’t mean the web-slinging stuff, which is used constantly to do nothing more than eat up time, I mean an entire sequence from an episode that has to last at least five minutes or more. It involves an underground civilization and the monstrous looking creatures that inhabit it. I thought I had already watched this episode and that my Netflix account was being glitch-ridden. Not so as it turns out thanks to a quick search on Wikipedia.

The third season must have roughly 15% new animation as the bulk of it is sliced and diced old episodes. Once more, the exact same villain actually, levitates Manhattan above the rest of New York. Vulture tries to commandeer and destroy a military gadget. Mysterio plans revenge on Spider-Man, and this instance has totally abandoned his traditional costume despite wearing it earlier on in the show’s run. These episodes are particularly rough to look at since they seem to have been made from well-worn materials.

And I don’t know what’s up the rogues gallery, but Spider-Man has a wealth of unique, colorful and interesting characters to choose from. The first season uses many of the most famous and adds a few new ones, but the second season abandons all of them for science-fiction storylines involving mad scientists, underground creatures and Nordic gods. This bizarre territory has a certain undefinable charm to it. Superhero shows are rarely allowed to get so surreal, even down-right head trippy. Comparing the first season to the latter ones is, frankly, hilarious.

The first season seems to exist in a knowing, obviously corny universe. There are good guys and bad guys, and they must each do their part in the action-packed story that has little or no time for character development or emotional investment. The backgrounds are clean, bright metropolitan cityscapes that are as Americana as apple pie, baseball, and you know the rest. Ralph Bakshi took over the main creative reigns beginning with season two and decided to make the show look more expressionistic and atmospheric. Suddenly the night skies became strange burst of black, purple and blue colors. Rocket Robin Hood, a silly sci-fi adventure show, was in production at the same time, and much of what was created for that show was recycled for this one. This explains the surreal, strange turn the whole enterprise took after a while.

If I’ve sounded like I hated the show, I didn’t. It held a curious charm, something you can’t quite put your finger upon. It’s easy to see how this became an internet meme, the show practically does it to itself in numerous occasions. I’m still trying to figure out why every female character that Peter Parker meets is a redhead who barely a stunning resemblance to Mary Jane, even though they’re never actually her until one episode where she’s turned into Captain Stacy’s niece and looks like a ginger Gwen Stacy.

But this show did provide the first adaptation of Spider-Man’s origin, and remains highly faithful given the constraints of children’s television, and Paul Soles does provide a nice voice for the character. Soles is fairly iconic at this point as the voice of the elf Hermey in Rudolph, and at times I couldn’t shake that mental image, it didn’t help that Paul Kligman plays his boss in both shows. But the “Gee whiz! Aw shucks” sweetness of the show, (un)intentional humor, crude animation and forward-momentum of the plots did make it easy, frequently enjoyable to watch.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Romance

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 26 March 2013 07:46

(A review of Romance)

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 26 March 2013 07:46

(A review of Romance)As a Garbo fan, many of her earliest “vamp” or “fallen women” roles are to be endured as they eventually gave way to gloriously rich and textured characters she would play in films like Queen Christina, Camille and Ninotchka. Anna Christie, which came out in the same year, at least presents a film that has atmosphere and a strong supporting cast. Anna Christie also has a character that is romatically haunted by her past, but refuses to remain a chastised victim of it. Here, she breaks his heart and is filmed in a saint-like way as the romance dies because he cannot overcome his high-mindedness and dis-proportioned naivety. Romance is without a doubt the weaker of the two films.

The problems are too numerous to mention, like with many early-sound films the pace and length of shots are problematic as the filmmakers don’t seem to know when to yell “Cut!” and transition to the next scene. The whole thing is rather stodgy and a frightful bore to look at. And our morally sound hero is a tremendous hypocrite and is no match for Garbo in the acting department. Gavin Gordon is an indifferent film presence, and even when Garbo is not operating at full-capacity, like she is here, she still manages to wipe him off of the screen by just being in the frame.

Gordon plays a young devout man who falls for Garbo’s opera singer, she’s a worldly and more experienced woman, and for this he renounces her and their romance. His petty arguments against her are doubly ironic given that he is studying to become a bishop, and doesn’t God want us to forgive ours and others trespasses? Gordon’s young man is highly unlikeable for much of the film, and when they don’t wind up together I was relived. He isn’t worthy of a woman as graceful, intelligent, sensual and passionate as Garbo. English is clearly a barrier for her performance, but she does what she can given the circumstances of the poor script and terrible supporting players. By no means a classic, or even really a good movie, but it offers another chance to stare at Garbo’s face in all of its luminous mysteries.

The problems are too numerous to mention, like with many early-sound films the pace and length of shots are problematic as the filmmakers don’t seem to know when to yell “Cut!” and transition to the next scene. The whole thing is rather stodgy and a frightful bore to look at. And our morally sound hero is a tremendous hypocrite and is no match for Garbo in the acting department. Gavin Gordon is an indifferent film presence, and even when Garbo is not operating at full-capacity, like she is here, she still manages to wipe him off of the screen by just being in the frame.

Gordon plays a young devout man who falls for Garbo’s opera singer, she’s a worldly and more experienced woman, and for this he renounces her and their romance. His petty arguments against her are doubly ironic given that he is studying to become a bishop, and doesn’t God want us to forgive ours and others trespasses? Gordon’s young man is highly unlikeable for much of the film, and when they don’t wind up together I was relived. He isn’t worthy of a woman as graceful, intelligent, sensual and passionate as Garbo. English is clearly a barrier for her performance, but she does what she can given the circumstances of the poor script and terrible supporting players. By no means a classic, or even really a good movie, but it offers another chance to stare at Garbo’s face in all of its luminous mysteries.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Santa Fe Trail

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 26 March 2013 07:23

(A review of Santa Fe Trail)

Posted : 12 years, 1 month ago on 26 March 2013 07:23

(A review of Santa Fe Trail)Entertaining, if not totally successful film that tries to combine a frontier adventure story with a moralizing message, Santa Fe Trail ends up being a bit of a mess, but it has its moments. Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland have a kind of chemistry that can make any piece of work watchable no matter its qualities, which is good since Trail needs a lot of help. They, along with director Michael Curtiz, made far better films in The Adventures of Robin Hood (arguably the masterpiece from the trio) and Captain Blood. While Santa Fe Trail is pretty horrific as history, but when has that ever been the strongest point in Hollywood storytelling, it’s also fairly problematic and tonally inconsistent about its desire to be either a romantic adventure story or a sermon-disguised-as-a-western.

For every great shoot ‘em up scene there’s another which positions abolitionists as zealots with quite a few loose screws, even if their end goal is justified. This split personality isn’t helped by any of the supporting actors – Raymond Massey and Van Heflin would turn in far better performances in other films and here decided to chew the scenery and act like ridiculous fire-and-brimstone caricatures. The film’s presentation of the black characters is both symptomatic of the times and a clear hedged-bet that they didn’t want to offend the southern audience. The presentation of blacks as child-like and naïve is something any viewer of old films will just have to get through, but once we’re told that they’re by and large completely ignorant of their circumstances I had reached my limit. But I will give the film credit for presenting the main characters as divided and shades of gray over the major conflict of the plot. They’re more like defined pros and cons engaging in debates that push the others to explore the murky middle ground, and it gets heavy-handed if well-intentioned at times. As for what the title has to do with the story – nothing other than a quick and cursory mention and stop. None of the main action has anything to do with the real Santa Fe Trail, so who knows why the film was dubbed this. To call it uneven would be putting it mildly, but Santa Fe Trail has its moments, I don’t know if the rest of the film is worth the trip to get to them, but if you’re a fan of Flynn, de Havilland or Curtiz, I suppose you must give it a glance.

For every great shoot ‘em up scene there’s another which positions abolitionists as zealots with quite a few loose screws, even if their end goal is justified. This split personality isn’t helped by any of the supporting actors – Raymond Massey and Van Heflin would turn in far better performances in other films and here decided to chew the scenery and act like ridiculous fire-and-brimstone caricatures. The film’s presentation of the black characters is both symptomatic of the times and a clear hedged-bet that they didn’t want to offend the southern audience. The presentation of blacks as child-like and naïve is something any viewer of old films will just have to get through, but once we’re told that they’re by and large completely ignorant of their circumstances I had reached my limit. But I will give the film credit for presenting the main characters as divided and shades of gray over the major conflict of the plot. They’re more like defined pros and cons engaging in debates that push the others to explore the murky middle ground, and it gets heavy-handed if well-intentioned at times. As for what the title has to do with the story – nothing other than a quick and cursory mention and stop. None of the main action has anything to do with the real Santa Fe Trail, so who knows why the film was dubbed this. To call it uneven would be putting it mildly, but Santa Fe Trail has its moments, I don’t know if the rest of the film is worth the trip to get to them, but if you’re a fan of Flynn, de Havilland or Curtiz, I suppose you must give it a glance.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Batman: Year One

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 11 March 2013 09:20

(A review of Batman: Year One)

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 11 March 2013 09:20

(A review of Batman: Year One)I don’t mean this as a criticism, but barring a few minor tweaks and adjustments, Batman: Year One is the most slavishly faithful adaptation of any of the DC direct-to-video films. It faithfully, in a sleeker and cleaner style, recreates the moody noirish look of the comic, complete with the muted colors and expressionist lighting. It also follows the novel’s penchant for character voiceover instead of length dialog passages and has a predominant amount of time devoted to Jim Gordon with Batman as a more ancillary character.

With numerous shots being practically a faithful recreation of panel by panel, if not pages by pages from the source material. Much of the ground will be immediately familiar to fans of Christopher Nolan’s astounding The Dark Knight Trilogy, but that should come as no surprise since Begins was based very heavily on Year One. And while this is an animated film, it doesn’t flinch away from the more adult aspects of the story. Scenes and sub-plots involve prostitution, drug trafficking, infidelity, child endangerment, police and government corruption and the fact that our hero bleeds so profusely remind us that comic books are often thought of in children’s entertainment terms but they are a valid art-form that frequently aim at a more adult audience.

The only real downslide is the voice acting, which is a mixed bag at best. Bryan Cranston is a gruff, tough Gordon and nails the character’s transition from more hopeful rookie to hardened beat-cop. The main female roles – Eliza Dushku as Catwoman, Katee Sackhoff as Sarah Essen and Grey Delisle as Sarah Gordon – perform their roles with grit and believability. Which leaves us with Ben McKenzie as Batman, and he doesn’t sell us on the part. I get that he was going for a younger, naïve and green Batman, but his boyish voice can’t convey the darkness and authority. McKenzie all too frequently sounds like a young kid play-acting as a grown-up.

The DVD includes a short film based upon Catwoman in which she breaks up a group of sex traffickers. It includes a scene in which she goes into a strip club to learn more about the location of the girls, which screams out as a future article for the Women in Refrigerators group. Not that they would have a hard time making the case that Catwoman performing a striptease was anything other than straight male service, but the short in general is strong with girl power. Catwoman takes down the gangster responsible in the name of friendship – her dear friend and cohort Holly is one of the girls who was kidnapped.

I’m not sure what it is about Batman that always allows for these creators to bring their A-Game to these films, but I appreciate it. Batman: Year One ranks pretty high in the list of these films. Now, if they could just turn this level of craft, care and attention to characters like Green Lantern, Aquaman, Flash, Wonder Woman, Green Arrow, hell, even a full-length solo Catwoman movie would be aces.

With numerous shots being practically a faithful recreation of panel by panel, if not pages by pages from the source material. Much of the ground will be immediately familiar to fans of Christopher Nolan’s astounding The Dark Knight Trilogy, but that should come as no surprise since Begins was based very heavily on Year One. And while this is an animated film, it doesn’t flinch away from the more adult aspects of the story. Scenes and sub-plots involve prostitution, drug trafficking, infidelity, child endangerment, police and government corruption and the fact that our hero bleeds so profusely remind us that comic books are often thought of in children’s entertainment terms but they are a valid art-form that frequently aim at a more adult audience.

The only real downslide is the voice acting, which is a mixed bag at best. Bryan Cranston is a gruff, tough Gordon and nails the character’s transition from more hopeful rookie to hardened beat-cop. The main female roles – Eliza Dushku as Catwoman, Katee Sackhoff as Sarah Essen and Grey Delisle as Sarah Gordon – perform their roles with grit and believability. Which leaves us with Ben McKenzie as Batman, and he doesn’t sell us on the part. I get that he was going for a younger, naïve and green Batman, but his boyish voice can’t convey the darkness and authority. McKenzie all too frequently sounds like a young kid play-acting as a grown-up.

The DVD includes a short film based upon Catwoman in which she breaks up a group of sex traffickers. It includes a scene in which she goes into a strip club to learn more about the location of the girls, which screams out as a future article for the Women in Refrigerators group. Not that they would have a hard time making the case that Catwoman performing a striptease was anything other than straight male service, but the short in general is strong with girl power. Catwoman takes down the gangster responsible in the name of friendship – her dear friend and cohort Holly is one of the girls who was kidnapped.

I’m not sure what it is about Batman that always allows for these creators to bring their A-Game to these films, but I appreciate it. Batman: Year One ranks pretty high in the list of these films. Now, if they could just turn this level of craft, care and attention to characters like Green Lantern, Aquaman, Flash, Wonder Woman, Green Arrow, hell, even a full-length solo Catwoman movie would be aces.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Fatal Attraction

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 11 March 2013 09:20

(A review of Fatal Attraction)

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 11 March 2013 09:20

(A review of Fatal Attraction)The story is pure melodramatic trash which sees the family foundation needing to be protected at all costs, but Glenn Close’s performance and Adrian Lyne’s stylish, tense direction make it worth viewing.

In fact, Close single-handedly elevates the entire movie from pulpy trash to Oscar caliber material. Her performance is a fierce, vulnerable and slowly unraveling turn of one woman’s break from reality and descended into sexual obsession, jealous and psychotic rage. In another year, she would/should have won the Oscar for Best Actress (she lost out to Cher in Moonstruck).

And for two-thirds of the run time Fatal Attraction appears to be a solidly written and incredibly well acted discourse on why men cheat and one woman’s fragile psyche. It isn’t until the last act rears its head that we’re suddenly thrust into a borderline slasher movie. Throughout Lyne showcases his unique visual eye – stylized colors and atmospheric shadows combined with odd angles. He gives the film an appropriately erotic and dangerous glow about it. And he manages to systematically ratchet up the tension. It comes in small spurts before we see the full breathed of just how traumatized and broken this woman is, and how far she intends to go to get him to take culpability for what he has done.

While the ending undermines it, you can’t help but admit that Close’s psychotic siren is right in her feminist rants: Michael Douglas’ character should have taken responsibility for his indiscretion. It may not be great art, but Fatal Attraction is a mostly well-done and juicy sexual thriller whose positives far outweigh the negatives.

In fact, Close single-handedly elevates the entire movie from pulpy trash to Oscar caliber material. Her performance is a fierce, vulnerable and slowly unraveling turn of one woman’s break from reality and descended into sexual obsession, jealous and psychotic rage. In another year, she would/should have won the Oscar for Best Actress (she lost out to Cher in Moonstruck).

And for two-thirds of the run time Fatal Attraction appears to be a solidly written and incredibly well acted discourse on why men cheat and one woman’s fragile psyche. It isn’t until the last act rears its head that we’re suddenly thrust into a borderline slasher movie. Throughout Lyne showcases his unique visual eye – stylized colors and atmospheric shadows combined with odd angles. He gives the film an appropriately erotic and dangerous glow about it. And he manages to systematically ratchet up the tension. It comes in small spurts before we see the full breathed of just how traumatized and broken this woman is, and how far she intends to go to get him to take culpability for what he has done.

While the ending undermines it, you can’t help but admit that Close’s psychotic siren is right in her feminist rants: Michael Douglas’ character should have taken responsibility for his indiscretion. It may not be great art, but Fatal Attraction is a mostly well-done and juicy sexual thriller whose positives far outweigh the negatives.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

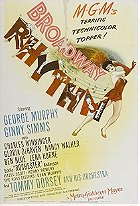

Broadway Rhythm

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 11 March 2013 09:20

(A review of Broadway Rhythm)

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 11 March 2013 09:20

(A review of Broadway Rhythm)It takes nearly two hours to tell this story: Broadway producer is mounting his next vehicle, wants movie star to be in it. Movie star doesn’t like his script, but the earlier one that the producer’s father (and former vaudeville star) wants to stage. Will the producer realize that his family and friends are some of the greatest talent in his proximity? It’s utterly forgettable and the definition of enervated monotony.

Broadway Rhythm is a prime example of how casting with star leads could make or break an otherwise uneven affair. Originally intended to star Eleanor Powell and Gene Kelly but winding up with George Murphy and Ginny Simms, the only decent acting performance from any of the main characters is from sardonic scene-stealer Nancy Walker. Her aggressive reactions to Dean Murphy’s impressions is a nice nod to what the audience was probably thinking and feeling about the impressionist, and the film by that point. The only redeeming feature of Rhythm is the series of specialty acts that pop up and liven up the film for sporadic and all too brief moments. Lena Horne gives “Brazilian Boogie” her typically sensual and sophisticated strength. She looks positively lovely, revealing her gorgeous legs in a high-slit dress, and gives most drag queens a lesson in how to perform with your face and hand gestures. Then there is the Russ Sisters who sing a song about potato salad before performing a dance routine that turns into contortionist feats. It’s borderline David Lynch weirdness in a lavish MGM musical. It’s memorable for both the amazing feats and acrobatics on display, and the sheer weirdness of the whole enterprise as they come rushing into a barn to sing their song and then twist around like pretzels. If Broadway had a few more moments like that, maybe I wouldn’t have started to fall asleep towards the end of it. It commits the cardinal sin of entertainment: it bores you.

Broadway Rhythm is a prime example of how casting with star leads could make or break an otherwise uneven affair. Originally intended to star Eleanor Powell and Gene Kelly but winding up with George Murphy and Ginny Simms, the only decent acting performance from any of the main characters is from sardonic scene-stealer Nancy Walker. Her aggressive reactions to Dean Murphy’s impressions is a nice nod to what the audience was probably thinking and feeling about the impressionist, and the film by that point. The only redeeming feature of Rhythm is the series of specialty acts that pop up and liven up the film for sporadic and all too brief moments. Lena Horne gives “Brazilian Boogie” her typically sensual and sophisticated strength. She looks positively lovely, revealing her gorgeous legs in a high-slit dress, and gives most drag queens a lesson in how to perform with your face and hand gestures. Then there is the Russ Sisters who sing a song about potato salad before performing a dance routine that turns into contortionist feats. It’s borderline David Lynch weirdness in a lavish MGM musical. It’s memorable for both the amazing feats and acrobatics on display, and the sheer weirdness of the whole enterprise as they come rushing into a barn to sing their song and then twist around like pretzels. If Broadway had a few more moments like that, maybe I wouldn’t have started to fall asleep towards the end of it. It commits the cardinal sin of entertainment: it bores you.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Black Pirate

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 6 March 2013 07:08

(A review of The Black Pirate)

Posted : 12 years, 2 months ago on 6 March 2013 07:08

(A review of The Black Pirate)Before there was Errol Flynn leading the charge in high-spirited adventures, there was Douglas Fairbanks, who not only created the mold from which numerous other stars have been remaking but pushed the form to its limits with practical effects and elaborate stunt work. Fairbanks was plainly handsome, but the real reason he is so infinitely watchable, exciting and an enduring artist in cinema was how he did death-defying stunts with a cheerful smile and a rogue sense of adventure. He may be a great big ham, but his exuberance and ease prove that sometimes screen acting is more than being able to read lines and convey deeper emotions.

If there are faults with The Black Pirate, and there are many within the narrative, none of them reflect back on the star who pushed for Technicolor to be used in this film. That was a smart move on his part since the primitive two-strip Technicolor process gives the whole film an illustrated manuscript gloss. Pirate frequently appears before our eyes as a live-action folktale. The Black Pirate doesn’t ask for much from its audience than to be entertained by the spectacle of the color and the swashbuckling aspects. It succeeds admirably on those grounds, and while the plot is too contrived by turns and filled with situations that are entirely too convenient and neat, at least it has a sense of fun and adventure about it.

It may not be the most stellar or artistically valuable of Fairbanks’ work, but it ranks amongst his best. Scenes of him single-handedly taking over a ship or leaping from one deck of the ship to another are filled with a passion for the art form that is infectious. It’s pure cinematic escapism, but it manages to pack in more heart, action, romance and wonder in roughly 90 minutes than other pirates films can pack in double that running time.

If there are faults with The Black Pirate, and there are many within the narrative, none of them reflect back on the star who pushed for Technicolor to be used in this film. That was a smart move on his part since the primitive two-strip Technicolor process gives the whole film an illustrated manuscript gloss. Pirate frequently appears before our eyes as a live-action folktale. The Black Pirate doesn’t ask for much from its audience than to be entertained by the spectacle of the color and the swashbuckling aspects. It succeeds admirably on those grounds, and while the plot is too contrived by turns and filled with situations that are entirely too convenient and neat, at least it has a sense of fun and adventure about it.

It may not be the most stellar or artistically valuable of Fairbanks’ work, but it ranks amongst his best. Scenes of him single-handedly taking over a ship or leaping from one deck of the ship to another are filled with a passion for the art form that is infectious. It’s pure cinematic escapism, but it manages to pack in more heart, action, romance and wonder in roughly 90 minutes than other pirates films can pack in double that running time.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections