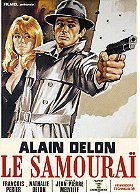

The movies are filled with beautiful killers and brooding, haunted men struggling with their past and present. But Alain Delon in Le Samourai puts practically all of them to shame. His performance is a master class in underplaying everything; he barely registers an emotion, keeping his cool poker face throughout the various twists and turns of the film.

His character, Jef Costello, is a hired killer, and bares very little resemblance to the true nature of a samurai, but around the edges and on the fringes of the concept his character does seem to overlap with samurai methodology. Honor and ethics have little to no value or place in Costello’s world. He serves himself, and seems eternally at an existential crossroads with his work and lifestyle. The faux-samurai ethos that opens the film lays bare the ideas of self-isolation at the core of the character.

This theme of self-isolation extends itself to numerous dialog free passages throughout the film. Delon barely says anything, but through various prolonged scenes where we see how he goes about his business we get a true sense of the character. Most of his acting is done through body movements and posture, and while his face may barely register any emotion, his body gives him away. Take the ending, in which Costello registers his upcoming death with no facial expression, but a relaxed and resigned body. He is not fighting his ultimate fate, and, hell, he may have been looking forward to this eventuality for a long time.

One of the other great things about Le Samourai’s very 60's European chic and coolness is the cinematography by Henri Decaë which offers up a dreamlike, almost poetic vision of France. This isn’t a remotely truthful vision or expression of French life in 1967, but the distilled and incredibly potent version of lone hired guns carried over from American films and given a European makeover. Decaë’s color palette is fixated on cold tones like grays or blues. But much of this cold exterior only works to bring up the heat going on beneath the surface.

The (justly) famous scene in which Delon tries to flee the cops using the underground metro looks as sterile as can be. But as the situation gets more and more intense, and as Delon constantly switches trains and plays with his pursuers, a real spark is being generated. And since the “action” payoffs are so minimal, almost incidental, the tension never truly gets a release. He just keeps switching trains, changing directions and leading the police to dead ends and misdirected locations. His escape comes with no large shootouts or anything grand happening. It’s the tension, the possibility of violence breaking out at any moment beneath the still, placid surfaces that gives the movie its edge.

The twisty, turny plot is like an exercise in practically every noir convention and clichéd story truism rolled into one. This doesn’t matter in the long run, because while Le Samourai may not tell an original story, it tells its story in an original way. The attention to tiny details truly broadens and strengthens not just the narrative, or development of characters through actions and scenery instead of conversations, but our appreciation of its craft.

I may still be confused over the specifics of who hired him, betrayed him, and what the piano player really has to do with it all – I feel like on a second viewing all of these disparate strands will come together to form a more cohesive whole, as it was more than likely intended to be. And even if further viewings don’t clear up some of my confusion, it doesn’t matter. The Big Sleep features an unresolved murder, an a nearly incomprehensible narrative, but it doesn’t matter. Sometimes an actor’s charisma, the style and look, the poetry (in this case) of a film is more interesting and important than narrative cohesion.

A scene that immediately springs to mind, a small touch really that explains so much yet is still slightly elusive, is a sequence involving a wiretap and a bird owned by Delon’s killer-for-hire. The specific’s involved are inconsequential to what I want to discuss, but the police end-up breaking into his apartment, and planting a wire. The bird, normally so calm and passive when Delon is around, flails about wildly in the cage. When Delon comes home, he sees the extra feathers and the calmed bird. He knows that something has occurred in the apartment, despite the fact that nothing else looks out of place.

His character’s keen eye is impeccable. And does he own the bird specifically to warn him of threats or changes that have occurred in his home? It seems to be that way. Why else would such an emotionally passive person own a pet? It’s a unique detail without a definitive answer, maybe it’s just a symbol. It’s the mystique that keeps Le Samourai so interesting, so ready for analysis and repeat viewings. To borrow a description that Alfred Hitchcock used for Grace Kelly, it’s a snow covered volcano of a film.

Le Samourai

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 28 September 2012 08:45

(A review of Le Samourai)

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 28 September 2012 08:45

(A review of Le Samourai) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Tonight and Every Night

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:54

(A review of Tonight and Every Night)

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:54

(A review of Tonight and Every Night)Part of the trade off of the studio era was for every film perfectly crafted to showcase the talents of their big names actors, like Rita Hayworth in this instance, there were a handful of other films that they were forced into working on because the formula worked once before. So, we had films like You Were Never Lovelier and Cover Girl, which showcased Hayworth’s talents as a dancer and actress (her singing was mimed in every musical/musical sequence she appeared in). And that’s how we ended up with this hot mess.

Tonight and Every Night tells a story about a London music hall that never stops performing, no matter if London is getting blitzed, the show must go on! Hayworth is an American in love with a RAF pilot. And she barely factors into many of the musical sequences of the film, and the story line is pretty thin on the dramatics side. The score is forgettable, with only two numbers being even slightly memorable. “You Excite Me” and “The Boy I Left Behind” showcase how Hayworth could easily use her body language to broadcast sexual desire and longing. “Excite” is also typically high-energy, if the rest of the film had come close to that musical number, there might have been something here. As it is, there’s lousy dialog, poorly written dramatics, an awful score, and pedestrian acting from many of her co-stars. Tonight and Every Night is a turkey.

Tonight and Every Night tells a story about a London music hall that never stops performing, no matter if London is getting blitzed, the show must go on! Hayworth is an American in love with a RAF pilot. And she barely factors into many of the musical sequences of the film, and the story line is pretty thin on the dramatics side. The score is forgettable, with only two numbers being even slightly memorable. “You Excite Me” and “The Boy I Left Behind” showcase how Hayworth could easily use her body language to broadcast sexual desire and longing. “Excite” is also typically high-energy, if the rest of the film had come close to that musical number, there might have been something here. As it is, there’s lousy dialog, poorly written dramatics, an awful score, and pedestrian acting from many of her co-stars. Tonight and Every Night is a turkey.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Salome

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:54

(A review of Salome)

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:54

(A review of Salome)At least there’s some entertainment value in Salome, sure, it’s as unintended homoeroticism and high-camp values, but there’s something there to keep things interesting. Salome purports to tell the Biblical story of John the Baptist, Salome, her dance of the seven veils, and the Baptist’s beheading. The problem is Harry Cohn, head of Columbia at the time, didn’t want his meal-ticket to play a seductive, scheming bitch. Even though her turns in Gilda and The Lady from Shanghai as seductive, scheming bitches are arguably her greatest acting achievements.

So, what we have here is a version of the story in which Salome is a duped innocent, and it’s her monstrous mother (Judith Anderson, in full-on drag queen diva mode) that’s pulling all of the strings. It’s pure Christian propaganda, too. With Charles Laughton’s King Herod being a weakling who does nothing out of voodoo-like fear of a vague prophecy discussing his doom if the Baptist should be harmed. His constant deferring to a mystic counselor and spineless encounters with his wife only highlight the Baptist’s claims that they’re too weak to rule.

Notice that I’ve barely mentioned Hayworth or Salome in this review thus far. That’s because in a film in which she is top billed and plays the titular character, Hayworth is more a large supporting role. She isn’t given much to work with, and has to rely upon her charisma and supernova-like star power to get her through. No problem, her charm and energy never dulled with age, even if her beauty was beginning to settle into a more mature look that’s wrong for the role. But she makes the Dance of the Seven Veils worth the trip, even if the cutaways to Laughton staring at her with bulged eyes and lascivious thoughts heighten the moment into pure camp theatricality.

Speaking of acting turning moments into campy hysterics, would someone please tell Alan Badel that playing a saint takes more than staring off into the distance and loudly pronouncing your message? His performance sinks the film beyond any repair. As he frequently just stares off into the distance with his eyes bulged out of his skull, and doesn’t seem self-possessed or divinely inspired, but self-assured, self-centered and cocky. And it’s not like Stewart Granger or Basil Sydney do much better, but there’s a certain layer of subtext to their scenes that at least makes them inadvertently enjoyable. Sydney asking Granger, practically embracing him in the process, why he doesn’t care as much for his comfort as the abused, half-naked slave is about as gay as it gets.

The central physicality and carnality of the story isn’t just toned down, it’s practically muted and muddled to the point of distraction. Anderson’s Queen Herodias being the prime example of this gigantic error, at once protective of Salome, having sent her away to escape the lusty glances of the king, and yet willing to let him rape Salome if it means he’ll kill John the Baptist for her. Salome hates men, falls for a secret Catholic and a Roman (Granger), does an erotic dance in hopes of freeing the Baptist, whose religion she just converted to in the previous scene with no prior interest or attention paid to his teachings, and then runs off with Granger to watch Jesus speak. No wonder Hayworth hid in the background of this mess. Thank God Laughton and Anderson decided to camp it up.

So, what we have here is a version of the story in which Salome is a duped innocent, and it’s her monstrous mother (Judith Anderson, in full-on drag queen diva mode) that’s pulling all of the strings. It’s pure Christian propaganda, too. With Charles Laughton’s King Herod being a weakling who does nothing out of voodoo-like fear of a vague prophecy discussing his doom if the Baptist should be harmed. His constant deferring to a mystic counselor and spineless encounters with his wife only highlight the Baptist’s claims that they’re too weak to rule.

Notice that I’ve barely mentioned Hayworth or Salome in this review thus far. That’s because in a film in which she is top billed and plays the titular character, Hayworth is more a large supporting role. She isn’t given much to work with, and has to rely upon her charisma and supernova-like star power to get her through. No problem, her charm and energy never dulled with age, even if her beauty was beginning to settle into a more mature look that’s wrong for the role. But she makes the Dance of the Seven Veils worth the trip, even if the cutaways to Laughton staring at her with bulged eyes and lascivious thoughts heighten the moment into pure camp theatricality.

Speaking of acting turning moments into campy hysterics, would someone please tell Alan Badel that playing a saint takes more than staring off into the distance and loudly pronouncing your message? His performance sinks the film beyond any repair. As he frequently just stares off into the distance with his eyes bulged out of his skull, and doesn’t seem self-possessed or divinely inspired, but self-assured, self-centered and cocky. And it’s not like Stewart Granger or Basil Sydney do much better, but there’s a certain layer of subtext to their scenes that at least makes them inadvertently enjoyable. Sydney asking Granger, practically embracing him in the process, why he doesn’t care as much for his comfort as the abused, half-naked slave is about as gay as it gets.

The central physicality and carnality of the story isn’t just toned down, it’s practically muted and muddled to the point of distraction. Anderson’s Queen Herodias being the prime example of this gigantic error, at once protective of Salome, having sent her away to escape the lusty glances of the king, and yet willing to let him rape Salome if it means he’ll kill John the Baptist for her. Salome hates men, falls for a secret Catholic and a Roman (Granger), does an erotic dance in hopes of freeing the Baptist, whose religion she just converted to in the previous scene with no prior interest or attention paid to his teachings, and then runs off with Granger to watch Jesus speak. No wonder Hayworth hid in the background of this mess. Thank God Laughton and Anderson decided to camp it up.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Rio Bravo

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:53

(A review of Rio Bravo)

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:53

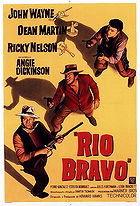

(A review of Rio Bravo)I guess we could call this one the anti-High Noon, since it tells a similar story, but doesn’t feature that film’s themes of alienation, cowardice, distrust and Red Scare symbolism. Instead, we have a band of outlaws, a sheriff willing and ready to protect the town, and a ragtag group of individuals who eagerly stand by his side throughout the whole ordeal. Oh, and we have a musical interlude and comedy, lots of it in the form of delicious witty and droll dialog.

There are a few things one that can always count on in any Howard Hawks film: good-to-career-best performances, a strong ensemble with an interesting and eclectic mixture of actors, an almost anarchic sense of forward motion in the narrative, and witty dialog. All of these elements are present in Rio Bravo. The only real problem with the movie is the uneven pacing, whenever it takes its leisurely time to do nothing in particular to advance the storyline proper, and it does this often, I feel like it could’ve been trimmed up to quicken the pace and give it a strong punch.

Which isn’t to say certain moments taken at a leisurely pace don’t work, because quite a few of them work spectacularly. The introduction is an astounding piece of filmmaking that only Hawks could get away with and enliven with such urgency. It’s, give or take, about five minutes long and there’s no dialog, just Dude (Dean Martin) wandering into town looking for some money to enable his alcoholism. When he stumbles back into town, he causes chaos in a saloon and the plot is off and running.

John Wayne is the sheriff, of course, and he does what he does best – act like a macho, he-man cowboy, the veritable symbol of the men who tamed the Wild West. He was never much of an actor, but for what he was capable of doing, he was the greatest. An as a bodily-focused actor, his drawl and tough-talk never wavered, he could make some interesting choices. His posture leaves much to be desired, frequently hunched over, or broken and contorted into odd shapes and angles, but these choices allow us to see the emotions within the character he was playing. That holds up as truth in Rio Bravo with any scene involving the lovely, fiery Angie Dickinson.

While Wayne is delivering a typical John Wayne performance, Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson (what the hell are they doing in a western anyway?) seem to be riffing on the kind of macho-centric performances that so many Western stars delivered. Martin’s drunk scenes are great, as are several scenes of his character going through withdrawal symptoms. But whenever he has to be the heroic character, it seems out of his prowess as an actor. Luckily, much of his character’s arch is in going from drunken stupor to rehabilitated hero, and this he nails. Nelson, oh so pretty and if I were a girl in the 50s I’d have a shrine to him in my bedroom, keeps his dialog to a minimum, but has a cocky swagger and a smirk that speak volumes. At times he seems to be trying out a John Wayne impression, and that works for the character, but he’s at his best whenever he’s allowed to be the cocky upstart to this group of old friends and aging cowboys. And while I enjoyed the musical interlude between Martin and Nelson while waiting for the shootout to occur, I don’t know how necessary it is to the plot. It seems like a concession to the audience that they couldn’t have these singers in the film and not have them sing, at least once.

Of course as the whole thing builds, slowly, to the climatic shootout, we get some hilarious dialog. Most of it delivered by Walter Brennan, who practically chews the scenery before spitting it back out into a spittoon. Brennan gets all of the biggest laughs, and he deserves as the cantankerous old man who may be a little crazy, but is still one of the best shots in the area. His character and performance recalls Walter Huston’s in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, but replace the tragedy and darkness from his character with the amped up comic undertones. Obviously and deservedly, he steals the film out from everyone.

And the lengthy climatic shootout brings together various disparate strands from the film – comedy, western, action/adventure – and merges them into something truly great. At first it’s just the three main characters – Wayne, Martin, Nelson – against the gang who has cut off the town, brought in the wealthy brother of their leader for help, and terrorized the whole town for the past three days. Soon various supporting players arrive to help them out in the struggle. As an answer to High Noon it does show the typical community spirit in so many westerns (and war-themed films), in which a band of outsiders come together to restore order and law. But I don’t think Rio Bravo understood the political and social allegory going on beneath the surface in High Noon. As I walked away from Rio Bravo, I remembered many of the comedic interludes, appreciated several of the performances, loved many of the sequences, but didn’t know what it was trying to communicate and I thought it could of used another go around in the editing process. I wouldn’t call this one a Hawks masterpiece like The Big Sleep, but it’s a grand entertainment none the less.

There are a few things one that can always count on in any Howard Hawks film: good-to-career-best performances, a strong ensemble with an interesting and eclectic mixture of actors, an almost anarchic sense of forward motion in the narrative, and witty dialog. All of these elements are present in Rio Bravo. The only real problem with the movie is the uneven pacing, whenever it takes its leisurely time to do nothing in particular to advance the storyline proper, and it does this often, I feel like it could’ve been trimmed up to quicken the pace and give it a strong punch.

Which isn’t to say certain moments taken at a leisurely pace don’t work, because quite a few of them work spectacularly. The introduction is an astounding piece of filmmaking that only Hawks could get away with and enliven with such urgency. It’s, give or take, about five minutes long and there’s no dialog, just Dude (Dean Martin) wandering into town looking for some money to enable his alcoholism. When he stumbles back into town, he causes chaos in a saloon and the plot is off and running.

John Wayne is the sheriff, of course, and he does what he does best – act like a macho, he-man cowboy, the veritable symbol of the men who tamed the Wild West. He was never much of an actor, but for what he was capable of doing, he was the greatest. An as a bodily-focused actor, his drawl and tough-talk never wavered, he could make some interesting choices. His posture leaves much to be desired, frequently hunched over, or broken and contorted into odd shapes and angles, but these choices allow us to see the emotions within the character he was playing. That holds up as truth in Rio Bravo with any scene involving the lovely, fiery Angie Dickinson.

While Wayne is delivering a typical John Wayne performance, Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson (what the hell are they doing in a western anyway?) seem to be riffing on the kind of macho-centric performances that so many Western stars delivered. Martin’s drunk scenes are great, as are several scenes of his character going through withdrawal symptoms. But whenever he has to be the heroic character, it seems out of his prowess as an actor. Luckily, much of his character’s arch is in going from drunken stupor to rehabilitated hero, and this he nails. Nelson, oh so pretty and if I were a girl in the 50s I’d have a shrine to him in my bedroom, keeps his dialog to a minimum, but has a cocky swagger and a smirk that speak volumes. At times he seems to be trying out a John Wayne impression, and that works for the character, but he’s at his best whenever he’s allowed to be the cocky upstart to this group of old friends and aging cowboys. And while I enjoyed the musical interlude between Martin and Nelson while waiting for the shootout to occur, I don’t know how necessary it is to the plot. It seems like a concession to the audience that they couldn’t have these singers in the film and not have them sing, at least once.

Of course as the whole thing builds, slowly, to the climatic shootout, we get some hilarious dialog. Most of it delivered by Walter Brennan, who practically chews the scenery before spitting it back out into a spittoon. Brennan gets all of the biggest laughs, and he deserves as the cantankerous old man who may be a little crazy, but is still one of the best shots in the area. His character and performance recalls Walter Huston’s in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, but replace the tragedy and darkness from his character with the amped up comic undertones. Obviously and deservedly, he steals the film out from everyone.

And the lengthy climatic shootout brings together various disparate strands from the film – comedy, western, action/adventure – and merges them into something truly great. At first it’s just the three main characters – Wayne, Martin, Nelson – against the gang who has cut off the town, brought in the wealthy brother of their leader for help, and terrorized the whole town for the past three days. Soon various supporting players arrive to help them out in the struggle. As an answer to High Noon it does show the typical community spirit in so many westerns (and war-themed films), in which a band of outsiders come together to restore order and law. But I don’t think Rio Bravo understood the political and social allegory going on beneath the surface in High Noon. As I walked away from Rio Bravo, I remembered many of the comedic interludes, appreciated several of the performances, loved many of the sequences, but didn’t know what it was trying to communicate and I thought it could of used another go around in the editing process. I wouldn’t call this one a Hawks masterpiece like The Big Sleep, but it’s a grand entertainment none the less.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Alice in Wonderland

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:53

(A review of Alice in Wonderland)

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:53

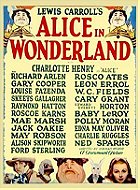

(A review of Alice in Wonderland)There’s something very unsettling about this version of Alice in Wonderland. Perhaps it’s the makeup and costuming which faithfully recreates the original drawings from the book(s) and places them on actors. The bloated faces, elongated limbs and animal-human hybrids translate as nightmarish creations in three-dimensions whereas on the page they could look charmingly asymmetrical and dreamily outlandish.

I think the level of performances have something to do with it. A vast group of character actors, up-and-comers (at the time) and big-name stars (again, at the time) deliver a wide range of performances. Cary Grant, unseen only heard, as the Mock Turtle reproves my point that he never slummed in any of his roles. Gary Cooper jettisons his normally stoic demeanor and dashing good looks for a more playful, senile knight. W.C. Fields is perfectly cast as Humpty Dumpty, the sheer absurdity of the whole enterprise fits his theatricality like a glove. And the three queens vary from outlandish (Edna May Oliver), petulant (May Robson) and utterly sweet-but-slightly-crazy (Louise Fazenda). Each of them turn in wonderful work, even if sequences involving two or more of them begin to get hallucinatory and confounding for just the sheer difference in acting styles alone.

The film didn’t really call for an all-star cast since most of them are covered in makeup, or it’s just their voices that we hear, and many of them are wasted in cameo roles. There’s so many characters and actors vying for attention that the film opens with a prolonged round-down of the cast members in and out of costume. This is achieved through a storybook pages being flipped through, as the actor’s head shot and name takes up one page, the next is a photo of them in costume and the character they play. And I think many of them overacted their little hearts out to try and survive against the insanity of the costumes and sets.

The croquet game uses real flamingos and hedgehogs, and there’s something unsettling about seeing real animals being used as props for an anarchic and fairly violent version of a subdued game. And the Mad Hatter’s tea party is enough to make you throw your hands up in the air and scream out “What the hell is this movie!?” I mean that in the best, most loving way possible. Even if the scene with the talking/singing pudding and mutton leg did freak me out and leave me very confused. But the Walrus and the Carpenter sequence was quite nice seeing as it involved animation from the Fleischer studio. I just wish that they had let it play out in full instead of cutting back and forth between the live actors telling the story and the animated sequence giving it full, spongy, bouncy life.

And what of Alice, Charlotte Henry, how does she fare in all of this? Well, I think her propulsive, forward moment is a nice touch for the character. But when really disturbing things happen to Alice in the book(s), she seems genuinely confused, disturbed and freaked out by it all. Henry has decided to take the all-smiling all-the-time approach. And that leads to sequences becoming horror film-lite in more than a few instances. The changing of the Duchess’ son from an infant into a pig should have freaked her out, at least a little. Here, Henry is charmed by the whole thing. Laughing, giggling and seemingly having great fun at the fact that a human infant just turned into a pig in her arms. This seems like a gross miscalculation on her part.

I don’t know if there has ever been a definitive film version of Alice in Wonderland. Sure, some viewers may pick this one, and it is a fine, wild, weird ride. The film is a true marvel of production design and costuming, even if it is unevenly acted and the storyline is Cliff Notes-esque. Others will choose the Disney version, or maybe one of the dozen televised versions. Maybe the episodic structure, clever wordplay and sheer bizarreness of the whole story are better suited to the page than the screen. It is imperfect, but it’s still a damn fine try at making a cohesive film out of the Alice stories.

I think the level of performances have something to do with it. A vast group of character actors, up-and-comers (at the time) and big-name stars (again, at the time) deliver a wide range of performances. Cary Grant, unseen only heard, as the Mock Turtle reproves my point that he never slummed in any of his roles. Gary Cooper jettisons his normally stoic demeanor and dashing good looks for a more playful, senile knight. W.C. Fields is perfectly cast as Humpty Dumpty, the sheer absurdity of the whole enterprise fits his theatricality like a glove. And the three queens vary from outlandish (Edna May Oliver), petulant (May Robson) and utterly sweet-but-slightly-crazy (Louise Fazenda). Each of them turn in wonderful work, even if sequences involving two or more of them begin to get hallucinatory and confounding for just the sheer difference in acting styles alone.

The film didn’t really call for an all-star cast since most of them are covered in makeup, or it’s just their voices that we hear, and many of them are wasted in cameo roles. There’s so many characters and actors vying for attention that the film opens with a prolonged round-down of the cast members in and out of costume. This is achieved through a storybook pages being flipped through, as the actor’s head shot and name takes up one page, the next is a photo of them in costume and the character they play. And I think many of them overacted their little hearts out to try and survive against the insanity of the costumes and sets.

The croquet game uses real flamingos and hedgehogs, and there’s something unsettling about seeing real animals being used as props for an anarchic and fairly violent version of a subdued game. And the Mad Hatter’s tea party is enough to make you throw your hands up in the air and scream out “What the hell is this movie!?” I mean that in the best, most loving way possible. Even if the scene with the talking/singing pudding and mutton leg did freak me out and leave me very confused. But the Walrus and the Carpenter sequence was quite nice seeing as it involved animation from the Fleischer studio. I just wish that they had let it play out in full instead of cutting back and forth between the live actors telling the story and the animated sequence giving it full, spongy, bouncy life.

And what of Alice, Charlotte Henry, how does she fare in all of this? Well, I think her propulsive, forward moment is a nice touch for the character. But when really disturbing things happen to Alice in the book(s), she seems genuinely confused, disturbed and freaked out by it all. Henry has decided to take the all-smiling all-the-time approach. And that leads to sequences becoming horror film-lite in more than a few instances. The changing of the Duchess’ son from an infant into a pig should have freaked her out, at least a little. Here, Henry is charmed by the whole thing. Laughing, giggling and seemingly having great fun at the fact that a human infant just turned into a pig in her arms. This seems like a gross miscalculation on her part.

I don’t know if there has ever been a definitive film version of Alice in Wonderland. Sure, some viewers may pick this one, and it is a fine, wild, weird ride. The film is a true marvel of production design and costuming, even if it is unevenly acted and the storyline is Cliff Notes-esque. Others will choose the Disney version, or maybe one of the dozen televised versions. Maybe the episodic structure, clever wordplay and sheer bizarreness of the whole story are better suited to the page than the screen. It is imperfect, but it’s still a damn fine try at making a cohesive film out of the Alice stories.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

I Was a Male War Bride

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:52

(A review of I Was a Male War Bride)

Posted : 12 years, 7 months ago on 21 September 2012 08:52

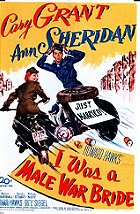

(A review of I Was a Male War Bride)That I Was a Male War Bride never rises to the propulsive, feverish comedic heights of films like Bringing Up Baby or Gentlemen Prefer Blondes can be easily forgiven, since it is Howard Hawks behind the lenses. You can’t hit a homerun every time at bat, but that it takes so long to get going is something of a problem. And Ann Sheridan seems out-gunned when next to Cary Grant, distinctly lacking the sardonic timing of Rosalind Russell or verbal-and-athletic sparing of Katharine Hepburn. Having said all of that, I Was a Male War Bride is still an enjoyable romp.

While the first half is off to a slow start, sometimes even boarding on the dull side of things, once our two main characters fall in love things pick up and its full steam ahead. Although during the first half a montage of Sheridan being put in the dominant position and Grant being forced to ride bitch is fairly amusing. Perhaps some of the problems I had with Sheridan can be traced back to the script. While Grant is given scenes which depict him sympathetically and prove how excellent of a farceur he was, Sheridan can come across as bitchy and mean-spirited, and not in an endearingly brassy way. Perhaps if she had been given a few more moments of warmth and tenderness I would have felt differently. Her work with James Cagney is always a treat, but maybe she’s more adept at being a gangster’s moll than a romantic comedy heroine. No matter in the end since the moment Grant steps onto the screen in full-on drag the film finally comes together in the appropriately madcap style that they had been going after all along. A pity the first half couldn’t match the tone of the second; we could have had something really special here.

While the first half is off to a slow start, sometimes even boarding on the dull side of things, once our two main characters fall in love things pick up and its full steam ahead. Although during the first half a montage of Sheridan being put in the dominant position and Grant being forced to ride bitch is fairly amusing. Perhaps some of the problems I had with Sheridan can be traced back to the script. While Grant is given scenes which depict him sympathetically and prove how excellent of a farceur he was, Sheridan can come across as bitchy and mean-spirited, and not in an endearingly brassy way. Perhaps if she had been given a few more moments of warmth and tenderness I would have felt differently. Her work with James Cagney is always a treat, but maybe she’s more adept at being a gangster’s moll than a romantic comedy heroine. No matter in the end since the moment Grant steps onto the screen in full-on drag the film finally comes together in the appropriately madcap style that they had been going after all along. A pity the first half couldn’t match the tone of the second; we could have had something really special here.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Kid

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 1 September 2012 05:17

(A review of The Kid)

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 1 September 2012 05:17

(A review of The Kid)Perhaps it’s because I saw this one after watching his lionized classics like City Lights, Modern Times, The Gold Rush, and The Great Dictator that I found The Kid to be more of a beautiful introductory for what was to come than a film that packs the same amount of weight and heft that the others contain. Maybe it’s also because it didn’t make me feel as joyous as I was expecting from a Chaplin film. The Kid is brilliant, but also very dark.

At only a little over an hour, The Kid tells its story with a tremendous amount of economy and heartbreaking imagery. It’s a simple story, really, but one full of melodrama – a young woman leaves her baby on a doorstep and is promptly found by the Tramp, who tries to pawn it offer and briefly considers leaving it to die, who takes it in and raises it as his son. The Tramp and the foundling are next seen five years later when the kid’s biological mother, now a famous actress, comes to the slums to do charity work with the street children and dreamily wishes she hadn’t abandoned her child. It’s obvious where the final scene will take us with this story, but that doesn’t matter.

For the most part, Chaplin sticks to this narrative and only presents us with a few truly memorable scenes. Namely, the sequence in which the child is taken away from the Tramp after it’s discovered that he is not the biological parent of the child. The Tramp’s mad dash over rooftops and through the slums to reach the truck taking the child away is exhilarating, but the reunion is the stuff that causes audiences to openly weep. The sheer joy that both the Tramp and the child have in being reunited is infectious, and one would have to be made out of steel to not feel the slightest bit moved by the whole thing. Before the film went into production, Chaplin lost his infant son, and that sense of loss and melancholia covers the whole film. So his naturalistic, almost animalistic recreation to being reunited with his son is coming from a very deep place.

A more curious sequence is the one that follows: after the rich woman realizes that the Tramp’s adoptive son is actually hers, she goes out and finds him, takes him away from the Tramp, and goes off to lead her happily-ever-after with the kid. The Tramp, devastated, goes out searching once more for the child. He rests after his grueling journey, and then we’re treated to a sequence showcasing his dreamworld. In his dream the Tramp and the kid are angels, blissfully together. Naturally, there are demonic interlopers who remove the child from the Tramp. It’s a strange little pantomime which sees the forces of the ghetto constantly trying to break the bound between father-and-son. It serves no real narrative purpose, but it’s symbolically pretty interesting ground to swim around in.

The Kid may not be his finest work, but it’s a lovely debut and showcases many of the idiosyncrasies which would appear again and again in his work. As a melodrama about a father-and-son relationship, it’s one of the few movies which justifiably will make you laugh until you cry, and then just cry. It’s without a doubt the best film I’ve seen about a loving father and son relationship, even if the bonds aren’t by blood.

At only a little over an hour, The Kid tells its story with a tremendous amount of economy and heartbreaking imagery. It’s a simple story, really, but one full of melodrama – a young woman leaves her baby on a doorstep and is promptly found by the Tramp, who tries to pawn it offer and briefly considers leaving it to die, who takes it in and raises it as his son. The Tramp and the foundling are next seen five years later when the kid’s biological mother, now a famous actress, comes to the slums to do charity work with the street children and dreamily wishes she hadn’t abandoned her child. It’s obvious where the final scene will take us with this story, but that doesn’t matter.

For the most part, Chaplin sticks to this narrative and only presents us with a few truly memorable scenes. Namely, the sequence in which the child is taken away from the Tramp after it’s discovered that he is not the biological parent of the child. The Tramp’s mad dash over rooftops and through the slums to reach the truck taking the child away is exhilarating, but the reunion is the stuff that causes audiences to openly weep. The sheer joy that both the Tramp and the child have in being reunited is infectious, and one would have to be made out of steel to not feel the slightest bit moved by the whole thing. Before the film went into production, Chaplin lost his infant son, and that sense of loss and melancholia covers the whole film. So his naturalistic, almost animalistic recreation to being reunited with his son is coming from a very deep place.

A more curious sequence is the one that follows: after the rich woman realizes that the Tramp’s adoptive son is actually hers, she goes out and finds him, takes him away from the Tramp, and goes off to lead her happily-ever-after with the kid. The Tramp, devastated, goes out searching once more for the child. He rests after his grueling journey, and then we’re treated to a sequence showcasing his dreamworld. In his dream the Tramp and the kid are angels, blissfully together. Naturally, there are demonic interlopers who remove the child from the Tramp. It’s a strange little pantomime which sees the forces of the ghetto constantly trying to break the bound between father-and-son. It serves no real narrative purpose, but it’s symbolically pretty interesting ground to swim around in.

The Kid may not be his finest work, but it’s a lovely debut and showcases many of the idiosyncrasies which would appear again and again in his work. As a melodrama about a father-and-son relationship, it’s one of the few movies which justifiably will make you laugh until you cry, and then just cry. It’s without a doubt the best film I’ve seen about a loving father and son relationship, even if the bonds aren’t by blood.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

THX-1138

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 1 September 2012 05:17

(A review of THX 1138)

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 1 September 2012 05:17

(A review of THX 1138)Perhaps it’s simply because THX-1138 doesn’t reside in the cultural memory in quite the same way that Star Wars does, but I think that this movie mostly survived George Lucas’ meddling unscathed. I say “I think” and “mostly” because I’ve never seen the non-meddled with/original version. But if this is any indication, maybe Star Wars was one of those two-headed behemoths that alternately was both the biggest blessing and the biggest curse to deal with, ever. And much like he couldn’t help rewriting history with that franchise, Lucas has taken his CGI-obsession to this film. The revisions are much smaller, smoother, and less noticeable overall. Except for one sequence at the end of the film in much it’s clearly a stand-in for Robert Duvall being attacked by CGI monkey/rat/dog-things.

Movies like American Graffiti and THX-1138 showcase Lucas’ talent for more small scale, but equally ambitious fare. And much of THX-1138 is deeply disturbing, and as electrifying and buzz-worthy now as when it was first released thanks to many of its ideas becoming more and more of a reality. The pilled-out, complacent nature of the unnamed only numbered society disturbed me to my core because of how close it is teetering to becoming common-place. What’s more interesting, in a far less disturbing way, is how it predicted creepily realistic holograms/special effects interacting amongst the populace. Look no further than the Coachella performance featuring a projection of Tupac that was a prime example of the Uncanny Valley theory.

But it’s the minimalism that allows for the film’s images to linger in the memory. The prison of sterile, hospital-like whiteness engulfing and consuming you is but one image of many. This isn’t just a prison; it’s a reminder that in the grand scheme of society, you are but an infinitesimal speck, a very tiny cog in a grand machine. It’s not just the everlasting expanse of pure white, but the way that Lucas frames them in the far off distance, or edits things to together to make it appear as though they were running in circles, or the asymmetricality that disorientates our understanding of the frame. I wonder what would of happened if he had followed this bleak, dystopian view-point instead of recreating his childhood serials in epic form. (And don’t get me wrong, I LOVE Star Wars. Hell, I themed by 25th birthday after it.)

Movies like American Graffiti and THX-1138 showcase Lucas’ talent for more small scale, but equally ambitious fare. And much of THX-1138 is deeply disturbing, and as electrifying and buzz-worthy now as when it was first released thanks to many of its ideas becoming more and more of a reality. The pilled-out, complacent nature of the unnamed only numbered society disturbed me to my core because of how close it is teetering to becoming common-place. What’s more interesting, in a far less disturbing way, is how it predicted creepily realistic holograms/special effects interacting amongst the populace. Look no further than the Coachella performance featuring a projection of Tupac that was a prime example of the Uncanny Valley theory.

But it’s the minimalism that allows for the film’s images to linger in the memory. The prison of sterile, hospital-like whiteness engulfing and consuming you is but one image of many. This isn’t just a prison; it’s a reminder that in the grand scheme of society, you are but an infinitesimal speck, a very tiny cog in a grand machine. It’s not just the everlasting expanse of pure white, but the way that Lucas frames them in the far off distance, or edits things to together to make it appear as though they were running in circles, or the asymmetricality that disorientates our understanding of the frame. I wonder what would of happened if he had followed this bleak, dystopian view-point instead of recreating his childhood serials in epic form. (And don’t get me wrong, I LOVE Star Wars. Hell, I themed by 25th birthday after it.)

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Houseboat

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 27 August 2012 09:07

(A review of Houseboat)

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 27 August 2012 09:07

(A review of Houseboat)Houseboat is proof that with the right movie stars, they make any old hackneyed script immensely watchable and enjoyable. It doesn’t help when the movie stars are as attractive and magnetic as Cary Grant and Sophia Loren. The screenplay is pure fluff and riddled with clichés – newly single father, unruly children, outsider who comes into the home and begins to fix everything, love story, new step-mom by the final scene – and is really only worth a look for Grant and Loren, and the one new idea it brings to the table. The new idea? That the children are real people who like the outsider as their friend, but may not like her as their new mom. The kids are conflicted about someone possibly “replacing” their mother and act out accordingly. Of course Cary Grant could do this kind of part blindfolded and backwards, but it still brings his normal level of energy and wit to the part. Say what you will about some of his lesser pictures, but I can’t think of a single time where Cary Grant was clearly slumming it for the paycheck. And Sophia Loren is an earthy sex goddess displaying a distinct talent for light comedy. She wears lovely outfits, looks gorgeous, earns her laughs, and more than holds her own against Grant, which is no easy task. Sure, it’s pure sitcom-level pastry dessert, but with two stars like these it’s worth watching at least once.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Invincible Iron Man

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 27 August 2012 09:06

(A review of The Invincible Iron Man)

Posted : 12 years, 8 months ago on 27 August 2012 09:06

(A review of The Invincible Iron Man)You know, it kind of saddens me to say this but…the direct-to-DVD DC film series doesn’t just outclass the Marvel films, they by and large are in a whole different category. Thus far I have seen five of the Marvel animated films, and I have really only enjoyed one from start to finish (Ultimate Avengers) and two in fits-and-starts (Hulk Vs and Ultimate Avengers 2). If you compare that to what DC has been putting out, it proves that Marvel has a lot of catching up to do in this department.

At least with this version of Iron Man we don’t have to deal with a snarky, fast-talking variation that started off fresh but is now a little played out. Tony Stark does maintain a sense of humor and a healthy appetite for buxom playmates, but the darkness, isolation and the meat of the character only roughly hinted at in the live action films remains intact. And that’s pretty much the only praise I can truly heap upon this film.

The animation and character designs are really no better than a well-produced and glossy cable channel show, or an imported anime. The fluidity leaves a little something to be desired, and the mouth movements don’t always sync up with the voices. Its little things like that which can quickly take one out of the world that’s being developed.

Another (major) problem is the villains who are both annoying stereotypes and severely underwritten and thrown off to the sidelines for much of the film. They offer no true threat, and look like every Street Fighter/anime/Eastern cliché thrown together. Oh, and they’re robots. This whole reductive Western = science, Eastern = magic/mysticism symbolism in the film is highly annoying and offensive failing to take a moment and think that the countries like Japan and China are mass producing and inventing most our newest technologies. If anything, there present day is combination of the two philosophies and an interior culture clash. But for the purposes of this film it’s easier to reduce it all down to the most basic, Cold War-era thinking.

At least with this version of Iron Man we don’t have to deal with a snarky, fast-talking variation that started off fresh but is now a little played out. Tony Stark does maintain a sense of humor and a healthy appetite for buxom playmates, but the darkness, isolation and the meat of the character only roughly hinted at in the live action films remains intact. And that’s pretty much the only praise I can truly heap upon this film.

The animation and character designs are really no better than a well-produced and glossy cable channel show, or an imported anime. The fluidity leaves a little something to be desired, and the mouth movements don’t always sync up with the voices. Its little things like that which can quickly take one out of the world that’s being developed.

Another (major) problem is the villains who are both annoying stereotypes and severely underwritten and thrown off to the sidelines for much of the film. They offer no true threat, and look like every Street Fighter/anime/Eastern cliché thrown together. Oh, and they’re robots. This whole reductive Western = science, Eastern = magic/mysticism symbolism in the film is highly annoying and offensive failing to take a moment and think that the countries like Japan and China are mass producing and inventing most our newest technologies. If anything, there present day is combination of the two philosophies and an interior culture clash. But for the purposes of this film it’s easier to reduce it all down to the most basic, Cold War-era thinking.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections