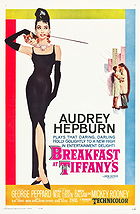

In a bit of expected Hollywood censorship, Truman Capote’s homosexual writer from the novella gets turned into a staunchly heterosexual stud in the film version of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Also rather odd, it makes explicit that George Peppard’s writer is a kept man and essentially a prostitute for an older woman, but skirts around Audrey Hepburn’s good-time girl’s hooker roots in the novella. Despite these problems, which also include the cringe-inducing xenophobic caricature that is Mickey Rooney in yellowface, Tiffany’s remains a charming and winsome bauble.

Hepburn stars as Holly Golightly, that self-made and delusional Manhattan hipster with the past that no one can piece together and the kind of issues that could keep most therapists in work for a lifetime. So strange that her image has become so hallowed since her character is just that, an image maintained and crafted by Golightly. When we do discover her past we understand why she escaped into this fantasy world of bright shiny things and meaningless friendships and parties in which she is the perfect hostess and the very image of urban elegance. She comes across as ditzy, even aggressively materialistic and shallow, at first, but by the end we understand and sympathize with her inner pain. She’s a lonely neurotic hiding behind a glossy chic and megawatt charm. If Hepburn hadn’t already won an Oscar for Roman Holiday, she should have won one for this (or The Nun’s Story).

Supporting her are a strong cast, chief amongst them is George Peppard, who is given little to do but stand around and look handsome. He does this well enough, but he comes across as rather stiff most of the time. But since he’s so hunky and knows the roots of Holly’s problems and doesn’t care, he comes across at times like a rock. He’s a solid support system that she needs, despite how much she rebels against her romantic feelings. Patricia Neal has a small but crucial role as Peppard’s older woman/sugarmama. She’s cold and cunning, a woman trapped in a loveless marriage to an older man who she clearly cannot stand. Not that she has any real affection for Peppard. He is just the latest in a long line of boy toys, once she’s done chewing him up and eviscerating him for choosing Holly over her, she’ll move on to a new one. And Buddy Ebsen as the mysterious Texan from Holly’s past, while a very small role, is tender and affection. He’s the lone character who doesn’t repel us at first. He has dignity and great love for Holly, even if she cannot reciprocate. She’s grateful to him, but he’s her past and she cannot/will not go back or revisit it.

Each and every character and situation that I have described is full of jagged edges and complex undertones, but Tiffany’s somehow never gets bogged down in them. It always remains humorous and the wistful score adds more to the fantasy and charm than anything else. Romantic comedies are hard to do, but Tiffany’s is effortless, in spite of the racist grotesquery that is Rooney’s character. It endures because it’s so enjoyable and charming, and is one of the few films which isn’t harpooned by its faults. That and Hepburn is a radiant presence throughout, giving us all of her fashionable glamor and delicate screen presence. She makes a delusional call-girl’s life look like the stuff of feathery dreams.

Breakfast at Tiffany's

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:07

(A review of Breakfast at Tiffany's)

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:07

(A review of Breakfast at Tiffany's) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Nun's Story

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:06

(A review of The Nun's Story)

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:06

(A review of The Nun's Story)The Nun’s Story was reportedly Audrey Hepburn’s favorite amongst the films she had made. It is easy to see why, not only does she deliver a performance of tremendous strength, delicate beauty and emotional complexity, but it’s one of the most honest depictions of true religious faith that I have seen. It positions that doing good and helping others sometimes means rejecting the dogma that bogs down religion and prevents them from getting into the trenches. That God and spiritual faith and righteousness are not found in the churches, and that they alone are not the only paths to living a moral and charitable life, but that these choices can be made from within. Sometimes an act of rebellion is the most perfect statement of faith. I make no secret about rejecting organized religion and seeking a more humanistic approach to life, and this story of a nun who leaves the convent because she cannot remain neutral in the onset of World War II is a tender and sensitive portrait of those ideals.

Directed by Fred Zinnemann, the maestro behind such classics as High Noon and From Here to Eternity, seemed to revel in stories about people engaging in situations and periods of time where their character and beliefs are tested, where heroism can be as different as standing up to wild west outlaws or your conscience dictating your fate. But instead of engaging in ham-fisted and overly melodramatic scenes to express these emotions he scaled back and turned down the drama. He was sensitive and quiet, empathetic to their choices and consequences. His choice to end the film with only the sound of Hepburn’s footsteps as she walks off into the Belgian streets during the earliest stages of WWII is as perfect and glorious a sequence as the ending of City Lights. His decision to not editorialize the moment with happy or sad music speaks to his empathetic treatment of his characters.

He could also frame and film movement wonderfully. Yes, we all think of the waves crashing on the beach and embracing lovers in From Here to Eternity, but what about the way he showcases how the nun’s go about their daily existence? The movement within them is composed and filmed like a classical dance piece. The movie does experience problems with pacing, as it does tend to lag in spots. Do we really need to meet so many different nuns and follow her through so many different jobs? I think the mental institution section could have been trimmed here and there and not much would have been lost. I suppose for people unconcerned with theological questions, crisis’s of faith and identity, and the inner turmoil to do what is right over what is expected this could be a real bore. There are no action sequences and it is relatively free of comedy. But there’s so much meat to sink your teeth into, so much glorious photography and those wondrous performances!

Audrey Hepburn is an actress and screen presence that I have always admired and enjoyed. There’s a certain fragility and quirky intelligence behind her eyes that adds a spark to her performances. She also possessed class, elegance, sophistication and wit – things which can’t be taught. And The Nun’s Story should silence anyone who doubts her prowess as an actress. She delivers a rich, fluent and complicated performance without the aide of aging makeup, costume changes and hair styles. The entire performance is interior and given by her face and large warm eyes.

The nun’s habit works as a frame for her exquisite instrument. She could project the passage of time and her character’s crisis's with a change in her body carriage and a look behind her eyes. That is acting at its finest. And something very interesting for Hepburn fans – in several movies we see her characters cut their hair from a long and luxurious cut to a pixie cut as a way to showcase their maturity from girlhood into womanhood. In essence, they have symbolically shed their innocence and virginal platitudes with their hair and have reemerged as sophisticated women. The Nun’s Story does an interesting twist to that device. Yes, her character gets her hair cut, but instead of a symbolical cutting to showcase that she is growing into her womanhood, she is cutting her hair to remain pure and virginal. She is cutting her hair to grow into a kind of chaste existence which her character might not have had before. And, at the end, when she removes her nun’s uniform, we see that her hair is still short but longer than it was before. Her character is growing her hair out as a way of embracing her womanhood and liberation.

While it is really Hepburn’s show, she is given able support from a cast that includes Academy Award winners Beatrice Straight, Peggy Ashcroft and Peter Finch, amongst numerous others. Finch in particular is given a rich character to portray and gives a great performance. He’s a doctor in the Belgian Congo and Hepburn is assigned to work as his aide. He loves that she is smart and shows a real interest in science, she has a natural apt for it. He’s also strongly sexually attracted to her. And she to him, and it is his magnetic sexuality and agnostic antagonism which bring out her character’s moral quandary. Her character was already experiencing these, and had been since joining, and he just helps her see that sometimes God and a life of good works and faith isn’t always housed in a building of stone. He rejects religious viewpoints, but he possesses a deep spirituality. Finch nails every nuance in his limited screen time.

Directed by Fred Zinnemann, the maestro behind such classics as High Noon and From Here to Eternity, seemed to revel in stories about people engaging in situations and periods of time where their character and beliefs are tested, where heroism can be as different as standing up to wild west outlaws or your conscience dictating your fate. But instead of engaging in ham-fisted and overly melodramatic scenes to express these emotions he scaled back and turned down the drama. He was sensitive and quiet, empathetic to their choices and consequences. His choice to end the film with only the sound of Hepburn’s footsteps as she walks off into the Belgian streets during the earliest stages of WWII is as perfect and glorious a sequence as the ending of City Lights. His decision to not editorialize the moment with happy or sad music speaks to his empathetic treatment of his characters.

He could also frame and film movement wonderfully. Yes, we all think of the waves crashing on the beach and embracing lovers in From Here to Eternity, but what about the way he showcases how the nun’s go about their daily existence? The movement within them is composed and filmed like a classical dance piece. The movie does experience problems with pacing, as it does tend to lag in spots. Do we really need to meet so many different nuns and follow her through so many different jobs? I think the mental institution section could have been trimmed here and there and not much would have been lost. I suppose for people unconcerned with theological questions, crisis’s of faith and identity, and the inner turmoil to do what is right over what is expected this could be a real bore. There are no action sequences and it is relatively free of comedy. But there’s so much meat to sink your teeth into, so much glorious photography and those wondrous performances!

Audrey Hepburn is an actress and screen presence that I have always admired and enjoyed. There’s a certain fragility and quirky intelligence behind her eyes that adds a spark to her performances. She also possessed class, elegance, sophistication and wit – things which can’t be taught. And The Nun’s Story should silence anyone who doubts her prowess as an actress. She delivers a rich, fluent and complicated performance without the aide of aging makeup, costume changes and hair styles. The entire performance is interior and given by her face and large warm eyes.

The nun’s habit works as a frame for her exquisite instrument. She could project the passage of time and her character’s crisis's with a change in her body carriage and a look behind her eyes. That is acting at its finest. And something very interesting for Hepburn fans – in several movies we see her characters cut their hair from a long and luxurious cut to a pixie cut as a way to showcase their maturity from girlhood into womanhood. In essence, they have symbolically shed their innocence and virginal platitudes with their hair and have reemerged as sophisticated women. The Nun’s Story does an interesting twist to that device. Yes, her character gets her hair cut, but instead of a symbolical cutting to showcase that she is growing into her womanhood, she is cutting her hair to remain pure and virginal. She is cutting her hair to grow into a kind of chaste existence which her character might not have had before. And, at the end, when she removes her nun’s uniform, we see that her hair is still short but longer than it was before. Her character is growing her hair out as a way of embracing her womanhood and liberation.

While it is really Hepburn’s show, she is given able support from a cast that includes Academy Award winners Beatrice Straight, Peggy Ashcroft and Peter Finch, amongst numerous others. Finch in particular is given a rich character to portray and gives a great performance. He’s a doctor in the Belgian Congo and Hepburn is assigned to work as his aide. He loves that she is smart and shows a real interest in science, she has a natural apt for it. He’s also strongly sexually attracted to her. And she to him, and it is his magnetic sexuality and agnostic antagonism which bring out her character’s moral quandary. Her character was already experiencing these, and had been since joining, and he just helps her see that sometimes God and a life of good works and faith isn’t always housed in a building of stone. He rejects religious viewpoints, but he possesses a deep spirituality. Finch nails every nuance in his limited screen time.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Long Day's Journey Into Night

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:05

(A review of Long Day's Journey Into Night)

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:05

(A review of Long Day's Journey Into Night)Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night is unquestionably a descent into one family’s personal hell, and perhaps his magnum opus. A work of autobiographical candor that laid bare the emotional scars and inner demons that drove his art. A film version could be a dangerous prospect; the magic of the stage is that since an entire section of their home is missing it makes us more than a voyeur. We are the silent fifth-member of the family, quite possibly the ghost of the dead-infant that is but one of the numerous problems causing the family to rot from the inside. Thankfully this film captures that same kind of emotional claustrophobia allowing for a similar kind of voyeurism to take place.

Much of this is achieved through the astounding moody and stylized cinematography from Boris Kaufman. A frequent collaborator of director Sidney Lumet, Kaufman and Lumet express a kind of filmic dialogue which allows us access into the Tyrone’s hellish world and very little reprieve from it. Very rarely do we escape from the interiors of the Tyrone’s dilapidated and consuming mansion, but when we do sunlight and trees look deadly and threatening. Faces look weather-beaten and damaged; rooms can be encroaching upon you with their shadows or made to engulf you with their disturbing openness and isolation. And the final image of the family sitting around a table completely surrounded by a circle of harsh white light does not evoke a heavenly pallor, but a disturbed and remote circle of the damned.

Night tells the story of the Tyrone clan, a four-member family each battling some form of addiction, who are stuck in a twisted emotionally co-dependent relationship based on mistrust and hatred. It’s one of those plays that actors dream about to not only display their skills but to enhance their craft. These roles are challenging for even the most talented of actors. They must walk that fine line between being shrieking narcissists that we hate and people we are completely enraptured by, even if we don’t particularly like them. This film version has been blessed with a cast that nails each and every challenge and nuance within the roles.

Lead by Katharine Hepburn, in a particularly brilliant piece of casting, as matriarch Mary, the cast is a force to be reckoned with. Hepburn’s natural intelligence, authority and independence add a nicely autobiographical touch to her reading of Mary. Her natural trembling adds a nice authenticity to the mercurial and deeply venomous character. She is all frayed nerves and pathetic abnegation. Hepburn was wisely nominated for an Academy Award for her performance here, and while I maintain that The Lion in Winter is her magnum opus as an actress I can fully appreciate and understand why some would chose this one instead. If any actress prospered more from aging than Hepburn I can’t think of them.

But the three men in the family don’t play second fiddle to Hepburn’s vicious mother. Ralph Richardson is the alcoholic father who pinched pennies on everything from doctors to the family to his son’s treatment facility. His vain attempts to buy up real estate and hide his alcoholism only point out the gap between his problems with addiction and self-realization, his responsibility for Hepburn’s morphine addiction further complicates matters. He denies his severe alcohol problems, but criticizes her for the “demon” within her. Jason Robards is the older son, an actor like his father who might show some kind of promise if he wasn’t in a permanent state of drunkenness. His father’s alcoholism looks “functional,” but Robards is in the midst of a full-blown downward spiral. It doesn’t help that he hates both of his parents and his younger brother. Robards is magnetic and fiery, a screen presence who is exceedingly commanding. Dean Stockwell, so young and attractive, is the younger brother who is slowly succumbing to TB. His mother hates him because she incorrectly blames him for the death of her youngest, his father wants to find the cheapest hospital he can find to shove him in, and his brother is angered that his very existence helped push their mother into drug addiction. It doesn’t help that Stockwell is the most together of the family, which Robards cannot abide. Stockwell is fey and quiet, but he to can also release his pent-up acid in large bursts. He is too soft in looks to survive in this world, and his fragility is pounced upon by his family. His focus and talent, the fact that he has a shot to get out of the psychological warfare, also drives Robards to hatred and jealousy. It’s a convoluted and messy tapestry of accusations and denial.

Unfairly, and very much unjustly, Hepburn was the only actor in this film to receive recognition from the Oscars. She lost to Anne Bancroft for The Miracle Worker, and the film was widely ignored upon release. Time has only been kind to every performance in the film. In another year they might have pulled off a Network-style acting sweep, and maybe the film would have been more widely recognized. This is an undervalued and underrated masterpiece. It’s also a great early work from master filmmaker Sidney Lumet. That alone should be worth your time.

Much of this is achieved through the astounding moody and stylized cinematography from Boris Kaufman. A frequent collaborator of director Sidney Lumet, Kaufman and Lumet express a kind of filmic dialogue which allows us access into the Tyrone’s hellish world and very little reprieve from it. Very rarely do we escape from the interiors of the Tyrone’s dilapidated and consuming mansion, but when we do sunlight and trees look deadly and threatening. Faces look weather-beaten and damaged; rooms can be encroaching upon you with their shadows or made to engulf you with their disturbing openness and isolation. And the final image of the family sitting around a table completely surrounded by a circle of harsh white light does not evoke a heavenly pallor, but a disturbed and remote circle of the damned.

Night tells the story of the Tyrone clan, a four-member family each battling some form of addiction, who are stuck in a twisted emotionally co-dependent relationship based on mistrust and hatred. It’s one of those plays that actors dream about to not only display their skills but to enhance their craft. These roles are challenging for even the most talented of actors. They must walk that fine line between being shrieking narcissists that we hate and people we are completely enraptured by, even if we don’t particularly like them. This film version has been blessed with a cast that nails each and every challenge and nuance within the roles.

Lead by Katharine Hepburn, in a particularly brilliant piece of casting, as matriarch Mary, the cast is a force to be reckoned with. Hepburn’s natural intelligence, authority and independence add a nicely autobiographical touch to her reading of Mary. Her natural trembling adds a nice authenticity to the mercurial and deeply venomous character. She is all frayed nerves and pathetic abnegation. Hepburn was wisely nominated for an Academy Award for her performance here, and while I maintain that The Lion in Winter is her magnum opus as an actress I can fully appreciate and understand why some would chose this one instead. If any actress prospered more from aging than Hepburn I can’t think of them.

But the three men in the family don’t play second fiddle to Hepburn’s vicious mother. Ralph Richardson is the alcoholic father who pinched pennies on everything from doctors to the family to his son’s treatment facility. His vain attempts to buy up real estate and hide his alcoholism only point out the gap between his problems with addiction and self-realization, his responsibility for Hepburn’s morphine addiction further complicates matters. He denies his severe alcohol problems, but criticizes her for the “demon” within her. Jason Robards is the older son, an actor like his father who might show some kind of promise if he wasn’t in a permanent state of drunkenness. His father’s alcoholism looks “functional,” but Robards is in the midst of a full-blown downward spiral. It doesn’t help that he hates both of his parents and his younger brother. Robards is magnetic and fiery, a screen presence who is exceedingly commanding. Dean Stockwell, so young and attractive, is the younger brother who is slowly succumbing to TB. His mother hates him because she incorrectly blames him for the death of her youngest, his father wants to find the cheapest hospital he can find to shove him in, and his brother is angered that his very existence helped push their mother into drug addiction. It doesn’t help that Stockwell is the most together of the family, which Robards cannot abide. Stockwell is fey and quiet, but he to can also release his pent-up acid in large bursts. He is too soft in looks to survive in this world, and his fragility is pounced upon by his family. His focus and talent, the fact that he has a shot to get out of the psychological warfare, also drives Robards to hatred and jealousy. It’s a convoluted and messy tapestry of accusations and denial.

Unfairly, and very much unjustly, Hepburn was the only actor in this film to receive recognition from the Oscars. She lost to Anne Bancroft for The Miracle Worker, and the film was widely ignored upon release. Time has only been kind to every performance in the film. In another year they might have pulled off a Network-style acting sweep, and maybe the film would have been more widely recognized. This is an undervalued and underrated masterpiece. It’s also a great early work from master filmmaker Sidney Lumet. That alone should be worth your time.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Summertime

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:04

(A review of Summertime)

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:04

(A review of Summertime)David Lean’s name immediately springs to mind such epic features as Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. Not a bad resume to have built a reputation and career off of, but it doesn’t quite explain Summertime. So this quiet little story about an American spinster taking a romantic trip through Venice to find love and recenter herself comes from the same man who put Peter O’Toole through hell in the desert? Proof that maybe David Lean’s reputation as a director wasn’t just for the grand epics that immediately spring to everyone’s mind; there was always a great attachment to characters and their journeys in his films. Summertime is like his Mrs. Dalloway, proving that a heroic character need not save the world or engage in battles to gain our admiration. Sometimes all they need to do is just blossom into the fullest and best version of their true self.

Katharine Hepburn, in one of her great spinster roles, stars as the vacationing American who meets a handsome Italian man and falls in a kind of love that she’s only ever heard of and read about. Her Venice is a blank canvas in which she can project her ideals and fantasies about life, culture, self-transformation and love. When the charming and frankly sexual Italian lover comes into her life, she’s shocked and aroused. Suddenly Venice becomes a solid and real place, the precocious little ragamuffin street urchin who accompanies her is a real boy who is really homeless and orphaned. The canals aren’t mystical waterways which transform strangers into lovers; they’re the polluted and murky life line of the city.

Summertime is thinly plotted for two obvious reasons: to allow for Katharine Hepburn to act her ass off, and for David Lean to point-and-shoot the gorgeous scenery with fabulous cinematography and great eye for details. The early parts of the film could have used some edits – how many times must I deal with that insufferable couple who do nothing but explore tourist traps and get no real flavor or picture of the places they visit? I find it strange that this was his alleged personal favorite film, since it is so thin in so many areas. The clichés of the plot and some of the visuals have dated badly, but the performances are like fine wines. While fireworks as visual image for sexual intercourse is as old and played out as the story-line, the way that Lean so loving frames and crafts the scene and has it shot is still wonderful to look at. And the way that Hepburn plays so much of it without words and just through long takes of her face and emoting is a wonder to behold. Summertime is just another example to add to my argument about Hepburn being one of the few actresses who only improved and obtained better work with age. With age came a softening and practical abandonment of all her mannered ticks and neurotic yammering that so hampered earlier films like Morning Glory.

Katharine Hepburn, in one of her great spinster roles, stars as the vacationing American who meets a handsome Italian man and falls in a kind of love that she’s only ever heard of and read about. Her Venice is a blank canvas in which she can project her ideals and fantasies about life, culture, self-transformation and love. When the charming and frankly sexual Italian lover comes into her life, she’s shocked and aroused. Suddenly Venice becomes a solid and real place, the precocious little ragamuffin street urchin who accompanies her is a real boy who is really homeless and orphaned. The canals aren’t mystical waterways which transform strangers into lovers; they’re the polluted and murky life line of the city.

Summertime is thinly plotted for two obvious reasons: to allow for Katharine Hepburn to act her ass off, and for David Lean to point-and-shoot the gorgeous scenery with fabulous cinematography and great eye for details. The early parts of the film could have used some edits – how many times must I deal with that insufferable couple who do nothing but explore tourist traps and get no real flavor or picture of the places they visit? I find it strange that this was his alleged personal favorite film, since it is so thin in so many areas. The clichés of the plot and some of the visuals have dated badly, but the performances are like fine wines. While fireworks as visual image for sexual intercourse is as old and played out as the story-line, the way that Lean so loving frames and crafts the scene and has it shot is still wonderful to look at. And the way that Hepburn plays so much of it without words and just through long takes of her face and emoting is a wonder to behold. Summertime is just another example to add to my argument about Hepburn being one of the few actresses who only improved and obtained better work with age. With age came a softening and practical abandonment of all her mannered ticks and neurotic yammering that so hampered earlier films like Morning Glory.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Circus

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:04

(A review of The Circus (1928))

Posted : 14 years, 4 months ago on 29 January 2011 08:04

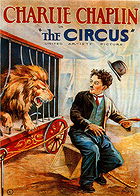

(A review of The Circus (1928))Like many great works of art, The Circus had a difficult birth. Born from a period of transition when Chaplin’s main form of artistic expression was turning from silent clowns to sound-and-visual spectacles, when his personal life was crashing all around him, and from his artistic perfectionism at all odds.

Until recently The Circus didn’t come up in the conversation about the greatest of Chaplin’s films, for whatever reason it had been deemed a minor triumph at best. Why that is, I have no clue. Could its scant running time have something to do with it? It runs barely over an hour, but just because it barely qualifies for feature length doesn’t mean it isn’t an exquisite series of segments which flow together beautifully, because it is. Could it be because it was released in-between acknowledged masterpieces The Gold Rush and City Lights? That seems like a silly reason. Or could it be because The Circus came out shortly after The Jazz Singer and was the last of Chaplin’s films to be entirely silent? His Tramp here feels a bit more existential and morose than the balletic comedian with delusions of grandeur in, say, Modern Times. Or could it be that since it was born from the collapse of one marriage and the troubled start of another, and that he knew his days as a mute comic were done, and that he made a point of not mentioning it in his autobiography, that popular culture followed suet and just left The Circus to be a footnote in his filmography? The true answer probably lies in some combination of them all. But it’s grossly unfair.

Let us speak of the plot now, which isn’t really a strong narrative rush forward as it is a brilliant string of comedic, sentimental and dramatic set-pieces which ebb and flow together so fluidly and beautifully. The Tramp is accused of stealing, not entirely wrongly, and escapes into a hall-of-mirrors and later a circus for refuge. As he stumbles blindly into an ongoing performance the crowd erupts into laughter and jubilant at the hilarious and hapless clown. Sensing a gold mine as long as he doesn’t know that he’s the star and so funny the ringmaster offers him a job. The Tramp quickly meets the ringmaster’s daughter, strikes up a friendship with her, generally runs amok in the circus, and helps her escape from the tyrannical rule of the ringmaster by helping her find true love.

To say that the Tramp is a Holy Fool is an understatement. He puffs his chest out and carries himself as a noble figure filled with an intelligence bought from the finest schools. But he’s also totally helpless and hapless with each situation he gets himself into by incorrectly reading body language and human interactions. Yet somehow, someway he can help those he interacts with, he can profoundly alter and change their lives. Paulette Goddard’s characters in Modern Times and The Great Dictator and the blind flower girl in City Lights are part of the rich tradition of the Tramp’s idiot savant redemptive powers.

And it is through his ability to transcend their lives but remain left behind and forgotten by the end that I mention this film as something of an elegy. An elegy not just for the great silent-film clowns like Chaplin but also Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, and possibly even for silent films themselves and the actors that the advent of sound just steam-rolled over. And since the advent of sound the great art of pantomime and vaudevillian slapstick, frat falls and acrobatic comedy has never really regained its composure. Chaplin had a background in these things, and perhaps he knew that with the advent of sound that film would move into fast-talking screwball comedy which played just as much with quips and acidic words as it did with a performer’s ability to fall and dangle with a dancer’s grace. Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Holiday and Bringing Up Baby came close, but falls nowadays have more to do with our collective schadenfreude than anything close to grace and wit.

But I am making the movie sound like some kind of overtly symbolic dramatic bore. There are so many wonderful comedic pieces to discuss. From his escaping the cops and pretending to be an animatronic figure who only attacks when his figure would logically do so through his repeated movements to the hall-of-mirrors sequence which has only been equaled by Orson Welles’ conclusion to The Lady From Shanghai, the comedy comes fast and furious and sometimes armed with sentimentality and pathos to match. Ah, yes, sentimentality, a word and emotion that has somehow become a symbol for everything cheap and easy. I beg to differ. There is nothing wrong with something that aims for good humor and bringing joy to others. The problem is that it is so rarely as well done as it is here nowadays.

But the real highlights of the film come in two sequences which mix high emotional stakes, danger and an artist’s breathtaking commitment to entertain his audience at all costs. The first of which sees the Tramp accidentally getting himself locked into a lion’s cage. As the beast sleeps the Tramp proceeds to pass out, check the side of the cage to see an angry tiger, drop metal plates, ask for help, get cocky and finally come running out screaming after the lion roars. Who saves him? Why, the ringmaster’s daughter, of course. The tension that he builds the entire time is amazing. That is a very real lion, and he is very obviously locked in a cramped space with it. When he comes running out, limbs flailing madly, the release is ecstatic.

The other is, of course, the climax of the film in which the Tramp performs a high-wire act to impress the girl he loves so dearly. Why a high-wire act? Because she has fallen in love with the circus’ high-wire stunt performer and he wants to win her back. He attaches a harness to himself, which breaks once he gets up there, and a pack of monkey’s attack him, which he released by accident earlier in the film. His clothes fall off of him and his dignity is at a loss. The audience stands up in a combination of joyous ovation and overwhelming dread. There is but one man sitting and eating popcorn, bemusedly smiling at the Holy Fool before him willing to die for his entertainment. That one scene probably more poetically and artistically captures my entire argument than the numerous words and paragraphs I have dedicated to it. Despite the alleged 200 takes to film the scene Chaplin made it all look so artful and effortless.

Until recently The Circus didn’t come up in the conversation about the greatest of Chaplin’s films, for whatever reason it had been deemed a minor triumph at best. Why that is, I have no clue. Could its scant running time have something to do with it? It runs barely over an hour, but just because it barely qualifies for feature length doesn’t mean it isn’t an exquisite series of segments which flow together beautifully, because it is. Could it be because it was released in-between acknowledged masterpieces The Gold Rush and City Lights? That seems like a silly reason. Or could it be because The Circus came out shortly after The Jazz Singer and was the last of Chaplin’s films to be entirely silent? His Tramp here feels a bit more existential and morose than the balletic comedian with delusions of grandeur in, say, Modern Times. Or could it be that since it was born from the collapse of one marriage and the troubled start of another, and that he knew his days as a mute comic were done, and that he made a point of not mentioning it in his autobiography, that popular culture followed suet and just left The Circus to be a footnote in his filmography? The true answer probably lies in some combination of them all. But it’s grossly unfair.

Let us speak of the plot now, which isn’t really a strong narrative rush forward as it is a brilliant string of comedic, sentimental and dramatic set-pieces which ebb and flow together so fluidly and beautifully. The Tramp is accused of stealing, not entirely wrongly, and escapes into a hall-of-mirrors and later a circus for refuge. As he stumbles blindly into an ongoing performance the crowd erupts into laughter and jubilant at the hilarious and hapless clown. Sensing a gold mine as long as he doesn’t know that he’s the star and so funny the ringmaster offers him a job. The Tramp quickly meets the ringmaster’s daughter, strikes up a friendship with her, generally runs amok in the circus, and helps her escape from the tyrannical rule of the ringmaster by helping her find true love.

To say that the Tramp is a Holy Fool is an understatement. He puffs his chest out and carries himself as a noble figure filled with an intelligence bought from the finest schools. But he’s also totally helpless and hapless with each situation he gets himself into by incorrectly reading body language and human interactions. Yet somehow, someway he can help those he interacts with, he can profoundly alter and change their lives. Paulette Goddard’s characters in Modern Times and The Great Dictator and the blind flower girl in City Lights are part of the rich tradition of the Tramp’s idiot savant redemptive powers.

And it is through his ability to transcend their lives but remain left behind and forgotten by the end that I mention this film as something of an elegy. An elegy not just for the great silent-film clowns like Chaplin but also Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, and possibly even for silent films themselves and the actors that the advent of sound just steam-rolled over. And since the advent of sound the great art of pantomime and vaudevillian slapstick, frat falls and acrobatic comedy has never really regained its composure. Chaplin had a background in these things, and perhaps he knew that with the advent of sound that film would move into fast-talking screwball comedy which played just as much with quips and acidic words as it did with a performer’s ability to fall and dangle with a dancer’s grace. Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Holiday and Bringing Up Baby came close, but falls nowadays have more to do with our collective schadenfreude than anything close to grace and wit.

But I am making the movie sound like some kind of overtly symbolic dramatic bore. There are so many wonderful comedic pieces to discuss. From his escaping the cops and pretending to be an animatronic figure who only attacks when his figure would logically do so through his repeated movements to the hall-of-mirrors sequence which has only been equaled by Orson Welles’ conclusion to The Lady From Shanghai, the comedy comes fast and furious and sometimes armed with sentimentality and pathos to match. Ah, yes, sentimentality, a word and emotion that has somehow become a symbol for everything cheap and easy. I beg to differ. There is nothing wrong with something that aims for good humor and bringing joy to others. The problem is that it is so rarely as well done as it is here nowadays.

But the real highlights of the film come in two sequences which mix high emotional stakes, danger and an artist’s breathtaking commitment to entertain his audience at all costs. The first of which sees the Tramp accidentally getting himself locked into a lion’s cage. As the beast sleeps the Tramp proceeds to pass out, check the side of the cage to see an angry tiger, drop metal plates, ask for help, get cocky and finally come running out screaming after the lion roars. Who saves him? Why, the ringmaster’s daughter, of course. The tension that he builds the entire time is amazing. That is a very real lion, and he is very obviously locked in a cramped space with it. When he comes running out, limbs flailing madly, the release is ecstatic.

The other is, of course, the climax of the film in which the Tramp performs a high-wire act to impress the girl he loves so dearly. Why a high-wire act? Because she has fallen in love with the circus’ high-wire stunt performer and he wants to win her back. He attaches a harness to himself, which breaks once he gets up there, and a pack of monkey’s attack him, which he released by accident earlier in the film. His clothes fall off of him and his dignity is at a loss. The audience stands up in a combination of joyous ovation and overwhelming dread. There is but one man sitting and eating popcorn, bemusedly smiling at the Holy Fool before him willing to die for his entertainment. That one scene probably more poetically and artistically captures my entire argument than the numerous words and paragraphs I have dedicated to it. Despite the alleged 200 takes to film the scene Chaplin made it all look so artful and effortless.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Glass Menagerie

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 26 December 2010 07:53

(A review of The Glass Menagerie)

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 26 December 2010 07:53

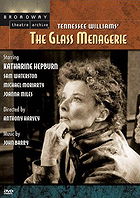

(A review of The Glass Menagerie)While given a full cinematic life, ok, as fully cinematic as a 70s-era TV-movie can get, there's something about this version of Tennessee Williams' seminal play that just hasn't translated properly. While much of the cast performs ably there have been too many alterations and removals from the text to give the proper flavor and musculature to the story. Without Tom's opening monologue telling us that everything we are about to view has been clouded by memory and emotion, that everything we are viewing is the truth but is being present as illusion, The Glass Menagerie loses some of the spark and fire that make it so richly alive. That omission of the opening monologue also causes us to lose the simple fact that this entire story takes place during the Depression, a social context that helps immensely to understand the frustration(s) of Tom as an artist in an era that asks him to be everything and anything but that.

Another major problem are the performances from the three main stars. Katharine Hepburn delivers an interesting take on Amanda Wingfield but is missing a certain spark. She lacks a once dewy sexuality with her severe angular features and the ability to project a kind of neurotic vulnerability. Her Amanda does not carry herself with the regality necessary, both in speech patterns and body language. Hepburn could have, and should have, been a fantastic choice for this part, but something is off here. Take the scene where the gentleman caller comes to visit and Amanda swoops in to charm him and seduce him, not sure any sexual reason but for an ego-stroking. She is too much of a tomboy, too strong-willed but appropriately eccentric. Taken out of the context of the play, this is a great performance. But (through no fault of her own given the amount of lines and contexts that have been removed) she seems too pushy with her children when she should remain loving and caring underneath her vainglorious daydreams and memories. It is so strange that she delivers a performance so at odds with the material when she turned in such perfect work in Williams' Suddenly, Last Summer.

Sam Waterson as Tom and Joanna Miles as Laura are good but never great. Waterson is too placid as Tom. There needs to be more a fire behind the eyes, a dream buried within himself that comes out in angry bursts against his mother, his sister, his life and job. But Tom also needs to view Amanda with more respect and resonance. Despite their disagreements these two people love each other very deeply. But is this a fault of Waterson's acting or of the removal of that opening monologue, of several of his monologues, which speak to us and explain the connective tissues between the frays and edges of their relationships. Tom also needs to love Laura, and this is a fault of Waterson's acting that he never quite sells it. One of the many reasons that Tom is so in conflict is that he feels a sense of responsibility for Laura, that he cannot leave her on her own, but he wants nothing more than to escape from his family. Miles is good, but never fully committed to the physical infirmities that plague her character. She sells the mental and emotional fragility, the timidness and shyness to the point of being handicapped.

The one performance that nails everything is Michael Moriarity as the gentleman caller. He is charming and alive, free from the shackles of this family's crazed co-dependence and damaged neediness. He is a fresh blast from the outside world that excites and stimulates them. Although his connection to the family is deep and full of history. His scenes with Laura are tender and wonderful, the best in the film.

The one last thing that keeps the film from being a truly great adaptation of Williams' play once again goes back to that opening monologue. This time it is a bit of stage-direction mentioned within it. This film should have taken place entirely within their apartment to give us a sense of claustrophobia. By keeping us within the apartment it would make us an accomplice to this family's struggles and fights. We'd be a fly-on-the-wall in their lives for a few hours. By turning the lights up and occasionally removing us from the confines of their St. Louis apartment we're given too clean a look at it all. And while everything should have been tainted with a look of dilapidation and hoarded memory, it all looks too pristine and new.

I have pointed out numerous faults in this adaptation, but I did not hate it. I'm just such a strong fan of the works of Tennessee Williams that faults and problems within adaptations become magnified to me. It's not even remotely terrible, but it's not as great an adaptation as A Streetcar Named Desire or Cat On a Hot Tin Roof. It's good, but never great. I don't think that Menagerie has been given a front-to-back classic film adaptation. Maybe Paul Newman's is the one, but I haven't seen it.

Another major problem are the performances from the three main stars. Katharine Hepburn delivers an interesting take on Amanda Wingfield but is missing a certain spark. She lacks a once dewy sexuality with her severe angular features and the ability to project a kind of neurotic vulnerability. Her Amanda does not carry herself with the regality necessary, both in speech patterns and body language. Hepburn could have, and should have, been a fantastic choice for this part, but something is off here. Take the scene where the gentleman caller comes to visit and Amanda swoops in to charm him and seduce him, not sure any sexual reason but for an ego-stroking. She is too much of a tomboy, too strong-willed but appropriately eccentric. Taken out of the context of the play, this is a great performance. But (through no fault of her own given the amount of lines and contexts that have been removed) she seems too pushy with her children when she should remain loving and caring underneath her vainglorious daydreams and memories. It is so strange that she delivers a performance so at odds with the material when she turned in such perfect work in Williams' Suddenly, Last Summer.

Sam Waterson as Tom and Joanna Miles as Laura are good but never great. Waterson is too placid as Tom. There needs to be more a fire behind the eyes, a dream buried within himself that comes out in angry bursts against his mother, his sister, his life and job. But Tom also needs to view Amanda with more respect and resonance. Despite their disagreements these two people love each other very deeply. But is this a fault of Waterson's acting or of the removal of that opening monologue, of several of his monologues, which speak to us and explain the connective tissues between the frays and edges of their relationships. Tom also needs to love Laura, and this is a fault of Waterson's acting that he never quite sells it. One of the many reasons that Tom is so in conflict is that he feels a sense of responsibility for Laura, that he cannot leave her on her own, but he wants nothing more than to escape from his family. Miles is good, but never fully committed to the physical infirmities that plague her character. She sells the mental and emotional fragility, the timidness and shyness to the point of being handicapped.

The one performance that nails everything is Michael Moriarity as the gentleman caller. He is charming and alive, free from the shackles of this family's crazed co-dependence and damaged neediness. He is a fresh blast from the outside world that excites and stimulates them. Although his connection to the family is deep and full of history. His scenes with Laura are tender and wonderful, the best in the film.

The one last thing that keeps the film from being a truly great adaptation of Williams' play once again goes back to that opening monologue. This time it is a bit of stage-direction mentioned within it. This film should have taken place entirely within their apartment to give us a sense of claustrophobia. By keeping us within the apartment it would make us an accomplice to this family's struggles and fights. We'd be a fly-on-the-wall in their lives for a few hours. By turning the lights up and occasionally removing us from the confines of their St. Louis apartment we're given too clean a look at it all. And while everything should have been tainted with a look of dilapidation and hoarded memory, it all looks too pristine and new.

I have pointed out numerous faults in this adaptation, but I did not hate it. I'm just such a strong fan of the works of Tennessee Williams that faults and problems within adaptations become magnified to me. It's not even remotely terrible, but it's not as great an adaptation as A Streetcar Named Desire or Cat On a Hot Tin Roof. It's good, but never great. I don't think that Menagerie has been given a front-to-back classic film adaptation. Maybe Paul Newman's is the one, but I haven't seen it.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Social Network

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 19 December 2010 05:23

(A review of The Social Network)

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 19 December 2010 05:23

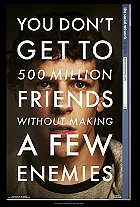

(A review of The Social Network)So it has come to this? A Best Picture nominee (trust me, those critics awards and word-of-mouth will lead to one) based very loosely on the creation of Facebook. Welcome to the area of People 2.0 in which every thought and emotion is worthy of attention and documentation, in which every minutia of their personality and day is available for broadcast 24/7 and connections between people are superficial and tangential at best. This is the time when we shall live upon the internet and Wall-E will no longer be a future-classic of modern filmmaking but a prophetic vision like Network, but family friendly. It is well acted, beautiful directed, possesses a score that I’m absolutely in love with and a wonderful script, but there’s something about it that just prevents me from wanting to jump the bandwagon and sing its praises.

I will not reiterate the storyline in the film, a quick Google search could tell you what’s real and what’s not and Wikipedia can give you a general synopsis, but I will begin with the script. Aaron Sorkin, the man’s reputation proceeds him, can create passages and bits of dialogue which can sound almost like a symphony score, or like a pretentious preponderance of sound and fury signifying nothing. Mostly he sticks the script firmly and adequately in the dialogue-as-symphony category, harking back to days of fast-paced witty scripts like His Girl Friday and the behind-the-scenes snark of Network. But every once in a while a choice will be made that screams of Sorkin’s overwrought tendencies to speechify and fall-in-love with his own prose. Such an example of this is the invention of Erica (Rooney Mara), the “Rosebud” to Mark Zuckerberg’s Kane. There is no Erica in real life, and there is no need for an Erica in the film. She is pointless and an obvious and easy shorthand for why he invented (stole, is more accurate, but we’ll get to that plot point later) Facebook.

The script is heavy in scenes of dialogue debating who Zuckerberg did and didn’t screw over to get Facebook off the ground. The short answer to that is: anyone and everyone. The courtroom scenes are minimal and work mostly as a framing device for the action of the story. It is in some of these scenes where Jesse Eisenberg’s performance really begins to unfold itself as something pretty special.

One could easily make the case that Mark Zuckerberg probably has Asperger’s syndrome and that he’s a huge asshole. Just take a look at any and all interviews with him. He practically refuses to blink and seems to have no basic shorthand or understanding for true human interaction. Like most extreme nerd-types, he seems frustrated with everyone in the world for being his inferior intellectually but lacks any true sense of how to interact, understand, sympathize or empathize with them. Perhaps this is why he never fell into the traps of fame and fortune at a young age, he doesn’t understand them. He really did freeze out and block out his best friend from the company. And he really did steal the idea for Facebook from his classmates. And he took that stolen idea and created it into a towering monument, a veritable phallic symbol for his ego. If he can’t get friends in real life, if he can’t connect with people face-to-face, then he’ll bring them to him in a language and area that he understands. (This is why the Erica character seems entirely superfluous and unnecessary, that and the already rampant misogyny.) He’s an unlikable choice for your main character, but Eisenberg makes all of this totally watchable. I’ve known types like Zuckerberg, and Eisenberg nails that particular type to utter perfection.

But that doesn’t mean any of the other characters are worth rooting for, not by any means. Armie Hammer and Andrew Garfield standout the most amongst the supporting cast as the people that Zuckerberg threw under the bus on his way to the top. Hammer portrays the Winklevoss twins and manages to create two distinct personality types that can function as a solid unit. If you’ve ever interacted with twins you’ll know what I’m talking about. And Garfield is Zuckerberg’s only friend who puts up the money to make the site and then sees his shares dwindle into nothing before being completely frozen out as the site goes global. They deserve sympathy for being royally screwed out of a multi-million (now billion) dollar idea, which they each clearly had some hand in laying the groundwork for. But they’re not terribly likeable. The Winklevi, as they’re acerbically referred to, offer both their fair share of laughs and sardonic wit, and the biggest bit of extraneous sequences. Especially their rowing scene on the Thames which I guess was supposed to showcase them being edged out of another of life’s little competitions while a remixed version of “Hall of the Mountain King” plays. Their extended slow-mo rowing and barely-there loss don’t neatly tie up dramatically, but left me asking “Why?”

And Justin Timberlake continues his winning streak of small supporting turns in films. Here he’s Sean Parker, the boy-king of Napster and an early case of internet-boom millions, who tries to lure Zuckerberg into the Silicon Valley. The Valley is portrayed as a den of sin and excess, which may be true for one of the businesses in that area, but I don’t see computer programming nerds living it up like this. The plethora of female-skin on display is partially to be expected, but the few female characters given any kind of a voice are barely drawn and sketched in. Erica is probably one of the only likeable people in the movie, but she’s out after the first scene and only returns for the briefest of cameos. We feel sympathy for having to endure the cruel barbs that come her way at the beginning and enjoy how ruthlessly she rejects Zuckerberg. Then she’s gone. And he assassinates her character online and an ugly misogyny streak comes out in the film. Brenda Song is your stereotypical crazy-girlfriend type, and Rashida Jones as a lawyer, the other likeable character, is a barely drawn afterthought. Jones’ lawyer exists more to give advice and deliver exposition then she is to be a character of any real weight or merit.

But Fincher always makes things visually interesting and keeps the pace moving very briskly. He can create a sense of urgency in something as painfully dull and painstakingly complicated as computer coding. And this is only his eighth film. And Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross deserve the Oscar this year for their score which combines classical and electronic sounds into something positively new and exciting. I rarely notice scores in films, but this one continually stood out to me. That should tell you of its power.

I’m unsure of this truly is the Best Picture of the year. I saw it shortly after it came out and the more I think about it the more I think that it’s just a very good, well-made character study. There’s an element of a zeitgeist relevancy to today, but I don’t consider myself a People 2.0, maybe a People 1.5.

I will not reiterate the storyline in the film, a quick Google search could tell you what’s real and what’s not and Wikipedia can give you a general synopsis, but I will begin with the script. Aaron Sorkin, the man’s reputation proceeds him, can create passages and bits of dialogue which can sound almost like a symphony score, or like a pretentious preponderance of sound and fury signifying nothing. Mostly he sticks the script firmly and adequately in the dialogue-as-symphony category, harking back to days of fast-paced witty scripts like His Girl Friday and the behind-the-scenes snark of Network. But every once in a while a choice will be made that screams of Sorkin’s overwrought tendencies to speechify and fall-in-love with his own prose. Such an example of this is the invention of Erica (Rooney Mara), the “Rosebud” to Mark Zuckerberg’s Kane. There is no Erica in real life, and there is no need for an Erica in the film. She is pointless and an obvious and easy shorthand for why he invented (stole, is more accurate, but we’ll get to that plot point later) Facebook.

The script is heavy in scenes of dialogue debating who Zuckerberg did and didn’t screw over to get Facebook off the ground. The short answer to that is: anyone and everyone. The courtroom scenes are minimal and work mostly as a framing device for the action of the story. It is in some of these scenes where Jesse Eisenberg’s performance really begins to unfold itself as something pretty special.

One could easily make the case that Mark Zuckerberg probably has Asperger’s syndrome and that he’s a huge asshole. Just take a look at any and all interviews with him. He practically refuses to blink and seems to have no basic shorthand or understanding for true human interaction. Like most extreme nerd-types, he seems frustrated with everyone in the world for being his inferior intellectually but lacks any true sense of how to interact, understand, sympathize or empathize with them. Perhaps this is why he never fell into the traps of fame and fortune at a young age, he doesn’t understand them. He really did freeze out and block out his best friend from the company. And he really did steal the idea for Facebook from his classmates. And he took that stolen idea and created it into a towering monument, a veritable phallic symbol for his ego. If he can’t get friends in real life, if he can’t connect with people face-to-face, then he’ll bring them to him in a language and area that he understands. (This is why the Erica character seems entirely superfluous and unnecessary, that and the already rampant misogyny.) He’s an unlikable choice for your main character, but Eisenberg makes all of this totally watchable. I’ve known types like Zuckerberg, and Eisenberg nails that particular type to utter perfection.

But that doesn’t mean any of the other characters are worth rooting for, not by any means. Armie Hammer and Andrew Garfield standout the most amongst the supporting cast as the people that Zuckerberg threw under the bus on his way to the top. Hammer portrays the Winklevoss twins and manages to create two distinct personality types that can function as a solid unit. If you’ve ever interacted with twins you’ll know what I’m talking about. And Garfield is Zuckerberg’s only friend who puts up the money to make the site and then sees his shares dwindle into nothing before being completely frozen out as the site goes global. They deserve sympathy for being royally screwed out of a multi-million (now billion) dollar idea, which they each clearly had some hand in laying the groundwork for. But they’re not terribly likeable. The Winklevi, as they’re acerbically referred to, offer both their fair share of laughs and sardonic wit, and the biggest bit of extraneous sequences. Especially their rowing scene on the Thames which I guess was supposed to showcase them being edged out of another of life’s little competitions while a remixed version of “Hall of the Mountain King” plays. Their extended slow-mo rowing and barely-there loss don’t neatly tie up dramatically, but left me asking “Why?”

And Justin Timberlake continues his winning streak of small supporting turns in films. Here he’s Sean Parker, the boy-king of Napster and an early case of internet-boom millions, who tries to lure Zuckerberg into the Silicon Valley. The Valley is portrayed as a den of sin and excess, which may be true for one of the businesses in that area, but I don’t see computer programming nerds living it up like this. The plethora of female-skin on display is partially to be expected, but the few female characters given any kind of a voice are barely drawn and sketched in. Erica is probably one of the only likeable people in the movie, but she’s out after the first scene and only returns for the briefest of cameos. We feel sympathy for having to endure the cruel barbs that come her way at the beginning and enjoy how ruthlessly she rejects Zuckerberg. Then she’s gone. And he assassinates her character online and an ugly misogyny streak comes out in the film. Brenda Song is your stereotypical crazy-girlfriend type, and Rashida Jones as a lawyer, the other likeable character, is a barely drawn afterthought. Jones’ lawyer exists more to give advice and deliver exposition then she is to be a character of any real weight or merit.

But Fincher always makes things visually interesting and keeps the pace moving very briskly. He can create a sense of urgency in something as painfully dull and painstakingly complicated as computer coding. And this is only his eighth film. And Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross deserve the Oscar this year for their score which combines classical and electronic sounds into something positively new and exciting. I rarely notice scores in films, but this one continually stood out to me. That should tell you of its power.

I’m unsure of this truly is the Best Picture of the year. I saw it shortly after it came out and the more I think about it the more I think that it’s just a very good, well-made character study. There’s an element of a zeitgeist relevancy to today, but I don’t consider myself a People 2.0, maybe a People 1.5.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Sunflower

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 19 December 2010 05:22

(A review of Sunflower)

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 19 December 2010 05:22

(A review of Sunflower)Sunflower, or as it is known in Italian I Girasoli, is a movie about how time continues to march on after war whether or not a person’s life does. Casualties on the battlefield is one way in which we discuss how brutal and total a war’s destruction was, but Sunflower offers another way to look at things: the collateral damage, which pertains not just to those civilians who are accidentally killed but to those whose lives are shattered by being in the general area. It makes the horrors of World War II in Italy accessible to us by focusing on how time marches on and leaves behind the broken emotional pieces of a man and a woman.

Vittorio de Sica, the maestro behind such classics as Marriage Italian Style and Yesterday Today and Tomorrow, directs this Italian film with his two favorite stars, Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, in a story that blends harsh neo-realist imagery with sentiment, touches of comedy and melodrama. Admittedly, the film could easily come across as overtly melodramatic, even sophomoric. And I could see where others might view the film as such. But de Sica was a wonderful director, and combing these kinds of tones and dealing with these storylines was his bread and butter. For me, the melodrama and sentiment is part of the specific Italian flavor in his films. It is also of historical note to point out that Sunflower was the first Western film to be shot in the Soviet Union.

But enough about the history of the film and its tone, Loren and Mastroianni play doomed lovers who meet-cute before the start of WWII, fall in love and marry. When he summoned off to war she helps him play insane in a large crowd to avoid the draft. It doesn’t work, and soon he goes missing while on the Russian front. Loren keeps the home fires burning and repeatedly tries to get a Visa to enter Russia and go searching for him. When she finally completes this she finds two things: a large unmarked gravesite which has seen turned into a field of sunflowers, a beautiful and depressing image about how time marches on after war even as we still suffer and try to heal our wounds in the aftermath; and that Mastroianni has remarried a Russian woman and has a child. He cannot leave this woman, who saved his life, and return to Italy for obvious reasons. So she returns and remarries someone else. He returns from Russian to see her one last time and make a play for her to reunite with him. But she has a child with her new husband, she cannot. And he returns once more to his life in Russia.

The performances really anchor the film and give it weight. In her American films Loren can give the impression of being a light-weight comedic actress, a sex symbol who is full of sensuality and charisma, but not an actress of tremendous depth. This is not true, and just illustrates further how Italian cinema knew what to do with her and American did not. She is an American film icon for foreign language films, no small feat that. Vittorio de Sica could create beautiful and heartbreaking performances with her (and hilariously volcanic comedic ones), and Sunflower is just as good as her work in Yesterday Today and Tomorrow and maybe as good as her work in Two Women. She returns to the well of her own life experiences during wartime Italy for this film and crafts another superb and aching portrait of a common woman who must overcome.

And Marcello Mastroianni is no slouch either. He does play second fiddle to Loren, but he can still hold his own ground. He must go from naughty-youth to wounded and disturbed soldier to an anonymous and broken man before finally ending the film as but a hollowed shell, a faded portrait of his once younger self. His performance is minimalist to the point of forgetting that he is even acting at all, much like his haunted director in 8 ½ . It’s always refreshing to see him tone down his work after the horn-dog maniacs he essayed in Yesterday Today and Tomorrow and Marriage Italian Style. Truly, he was an absolute acting great and treasure and testament to power and joys of Italian and foreign cinema.

Vittorio de Sica, the maestro behind such classics as Marriage Italian Style and Yesterday Today and Tomorrow, directs this Italian film with his two favorite stars, Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, in a story that blends harsh neo-realist imagery with sentiment, touches of comedy and melodrama. Admittedly, the film could easily come across as overtly melodramatic, even sophomoric. And I could see where others might view the film as such. But de Sica was a wonderful director, and combing these kinds of tones and dealing with these storylines was his bread and butter. For me, the melodrama and sentiment is part of the specific Italian flavor in his films. It is also of historical note to point out that Sunflower was the first Western film to be shot in the Soviet Union.

But enough about the history of the film and its tone, Loren and Mastroianni play doomed lovers who meet-cute before the start of WWII, fall in love and marry. When he summoned off to war she helps him play insane in a large crowd to avoid the draft. It doesn’t work, and soon he goes missing while on the Russian front. Loren keeps the home fires burning and repeatedly tries to get a Visa to enter Russia and go searching for him. When she finally completes this she finds two things: a large unmarked gravesite which has seen turned into a field of sunflowers, a beautiful and depressing image about how time marches on after war even as we still suffer and try to heal our wounds in the aftermath; and that Mastroianni has remarried a Russian woman and has a child. He cannot leave this woman, who saved his life, and return to Italy for obvious reasons. So she returns and remarries someone else. He returns from Russian to see her one last time and make a play for her to reunite with him. But she has a child with her new husband, she cannot. And he returns once more to his life in Russia.

The performances really anchor the film and give it weight. In her American films Loren can give the impression of being a light-weight comedic actress, a sex symbol who is full of sensuality and charisma, but not an actress of tremendous depth. This is not true, and just illustrates further how Italian cinema knew what to do with her and American did not. She is an American film icon for foreign language films, no small feat that. Vittorio de Sica could create beautiful and heartbreaking performances with her (and hilariously volcanic comedic ones), and Sunflower is just as good as her work in Yesterday Today and Tomorrow and maybe as good as her work in Two Women. She returns to the well of her own life experiences during wartime Italy for this film and crafts another superb and aching portrait of a common woman who must overcome.

And Marcello Mastroianni is no slouch either. He does play second fiddle to Loren, but he can still hold his own ground. He must go from naughty-youth to wounded and disturbed soldier to an anonymous and broken man before finally ending the film as but a hollowed shell, a faded portrait of his once younger self. His performance is minimalist to the point of forgetting that he is even acting at all, much like his haunted director in 8 ½ . It’s always refreshing to see him tone down his work after the horn-dog maniacs he essayed in Yesterday Today and Tomorrow and Marriage Italian Style. Truly, he was an absolute acting great and treasure and testament to power and joys of Italian and foreign cinema.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

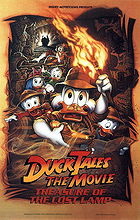

DuckTales: Treasure of the Lost Lamp

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 19 December 2010 05:21

(A review of DuckTales: The Movie - Treasure of the Lost Lamp)

Posted : 14 years, 5 months ago on 19 December 2010 05:21

(A review of DuckTales: The Movie - Treasure of the Lost Lamp)Intended to be the first of a franchise, which never really took off, DuckTales: Treasure of the Lost Lamp is an enjoyable but uneven film. There are times when the animation and vocal work are at the level of the high-gloss studio films, and there are times when it looks, sounds and is written no better than any of Disney’s TV shows. The cut-corners are glaringly obvious, but there’s still a certain charm and good nature to this tale of Scrooge McDuck and co. Basically, it’s a riff on Arabian Nights with McDuck after the treasure of Collie Baba (get it?), finding a lost lamp and giving it to Webby, his adopted niece. Of course it contains a magical genie (voiced by Rip Taylor, who is manic and hilarious), and of course there is a magical villain who wants to repossess the lamp and the genie (Christopher Lloyd). While predictable, it still contains numerous moments of pure joy and fun such as Huey, Dewy and Louie wishing for ice cream to rain down for the sky or Webby wishing for all of her stuffed animals come to life. It’s frivolous and kind of forgettable unless you grew up with it like I did.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Hejira

Posted : 14 years, 6 months ago on 20 November 2010 02:38

(A review of Hejira)

Posted : 14 years, 6 months ago on 20 November 2010 02:38

(A review of Hejira)Written during a road trip from Maine to California, Hejira (an Arabic word meaning ‘journey’) is the last in an astonishing run of six albums to come from Joni Mitchell’s most fruitful and creative period during the seventies. Filled with her weird and distinctive chords, layered and haunted backing vocals and explorations into folk-jazz-pop-rock, Hejira could be seen as the summarization of her work throughout the seventies. The transitional album from her earlier singer-songwriter/folkie period to the latter day jazz-rock weirdo, Hejira still has enough artistic merit and worthwhile songs to recommend it on its own and as just some historical artistic document.

Here, more so than on any previous effort, Mitchell has forsaken melody and typical song structure for a more musical variation of poetry/language accompanied by music. Because of this it’s harder to talk about each song as an individual piece of work when they clearly are just a small unit for a cohesive whole. To put it more bluntly: this is an album, in the true sense of the word. There’s no easy to define single, no big pop-rock ditty that seems destined for radio presence. Naturally, it did well critically but disappointed commercially. But what could you expect from an album which features a song about a protagonist driving across country and praying/empathizing/sympathizing with Amelia Earhart that constantly shifts between two different chords? Or an album that features a song as languorous, smoky and lived like “Blue Motel Room” to almost close out the album?

But there must be tremendous kudos paid for Mitchell continually painting some varied and kaleidoscopic portraits of a woman’s reality. Sometimes they’re clearly autobiographical and other times they’re purely works of fiction. Or perhaps they’re based on people she encountered along the way and created entire stories and emotional problems for them. “Song for Sharon” is ambivalent and features a protagonist who must choose between personal freedom and domesticity. Welcome to life post-Summer of Love and post-feminist movement. On the front cover Mitchell looks like the Mother of the Roads. Dressed in black with her long blonde hair blowing to the side and standing against a frozen landscape with an empty and long stretch of highway imposed on her torso, Mitchell knows and understands your loneliness and conflicts. On the back she is ice skating, but all of her long black clothing gives the impression that she is a raven flying away from it all. She’s been there with you. It’s a dark, complicated but very rewarding listening experience. DOWNLOAD: “Amelia”

Here, more so than on any previous effort, Mitchell has forsaken melody and typical song structure for a more musical variation of poetry/language accompanied by music. Because of this it’s harder to talk about each song as an individual piece of work when they clearly are just a small unit for a cohesive whole. To put it more bluntly: this is an album, in the true sense of the word. There’s no easy to define single, no big pop-rock ditty that seems destined for radio presence. Naturally, it did well critically but disappointed commercially. But what could you expect from an album which features a song about a protagonist driving across country and praying/empathizing/sympathizing with Amelia Earhart that constantly shifts between two different chords? Or an album that features a song as languorous, smoky and lived like “Blue Motel Room” to almost close out the album?

But there must be tremendous kudos paid for Mitchell continually painting some varied and kaleidoscopic portraits of a woman’s reality. Sometimes they’re clearly autobiographical and other times they’re purely works of fiction. Or perhaps they’re based on people she encountered along the way and created entire stories and emotional problems for them. “Song for Sharon” is ambivalent and features a protagonist who must choose between personal freedom and domesticity. Welcome to life post-Summer of Love and post-feminist movement. On the front cover Mitchell looks like the Mother of the Roads. Dressed in black with her long blonde hair blowing to the side and standing against a frozen landscape with an empty and long stretch of highway imposed on her torso, Mitchell knows and understands your loneliness and conflicts. On the back she is ice skating, but all of her long black clothing gives the impression that she is a raven flying away from it all. She’s been there with you. It’s a dark, complicated but very rewarding listening experience. DOWNLOAD: “Amelia”

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections