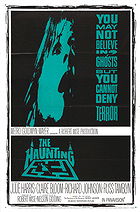

Shirley Jackson’s seminal haunted house novel gets the film adaptation treatment deserving of its artistry and exemplary skill in Robert Wise’s 1963 feature, The Haunting. He captures the emotional unease of the characters, most notably Eleanor, so well and all without displaying a ghostly vision. No matter, the atmosphere of sustained uncertainty and terror he creates makes you somehow convinced that there were spectral presences hidden away in the corners of the frame.

The film follows the novels various character studies and beats expertly. We’re gathered here for academic purposes, those of Professor John Markway to be exact, and the three others we meet are here as test subjects for detecting supernatural phenomena. We’ve got Luke, living heir to the mansion’s property, Theo, a chic, cool woman with an empathy for the supernatural, and Eleanor, a frazzled, mercurial, emotionally unstable woman chosen for her documented experience with a strange phenomena. They’re to stay in Hill House and document what they see, hear, and feel.

All of that is a fun bit of setup for what’s to follow: the complete psychological and emotional collapse of Eleanor. Whether this is by spectral means, she feels “chosen” and compelled to the house by unseen forces, or because of her demonstrable mental and emotional issues is left vague enough to argue either side. What’s for certain is that Eleanor is not a reliable protagonist, and to experience the haunting through her prism is deeply unnerving.

Much like Jackson’s prose, Wise grounds in the proceedings in a recognizably real world and works hard to keep things just out of sight. This makes your mind fill in the blanks as to what is truly going on. Cacophonous banging in the middle of the night, wallpaper that looks like an angry face in the right combination of shadows and light, inexplicably cold spots in the middle of the room – these are the horrors that grip Eleanor and company, and all of them are tangible.

Wise’s film is also armed with a sense of craft that elevates it into greatness and far away from goofy translucent ghosts. The sound design of a late-night banging is all the more terrifying for the pauses that happen in-between them. First they drip out slowly, then manically, then there’s a long agonizing pause as we wait as the characters do to see if it’s over yet or not. There’s also the disorientating nature of the house’s production design as walls are angled curiously, doors lead to bent hallways or into other rooms that they didn’t appear to lead into before. The entire house keeps both the characters and the audience off-balance that heightens the air of mystery and danger about the place.

There’s also the camera work that frequently lingers in tight close-ups of its actors faces as they stare off camera at whatever imagined horrors are turning knobs, closing doors, or writing on walls. There’s one particular bravura piece where Eleanor wanders outside away from the group, looks up at something on the outside of the house, then the camera switches to the perspective of that terrorizing object as it quickly descends onto a screaming Eleanor. It’s a flourish to be certain, but an extremely effective one. We’re never quite sure what Eleanor saw, but we’re unnerved by the suggestion and her frayed response to it.

Finally, there’s the strength of the four lead actors that make The Haunting work so beautifully. Richard Johnson’s appropriately stuffy, academic, and fatherly as Prof. Markway, and Russ Tamblyn gets to be comedic relief that quickly wilts in the face of what he experiences as time goes on. Yet it’s the two leading ladies that make the biggest impression here.

Claire Bloom makes Theo a fetching, icy Mod goddess. Dressed in black, quick with a cutting remark, and subtly playing the character’s lesbianism, Bloom makes Theo a scene-stealer whenever she can. Her quacking in the face of ghostly apparitions, explained away as a sensitivity that manifests as full-body chill, is a tightly controlled bit of bodily acting. Her impassive face rarely displays the terror, arousal, or exasperation that her character feels. It’s all through implication of her body language or a quick glance or change in her eyes.

But it’s Eleanor’s story in the end, and Julie Harris expertly goes about her task of playing an exposed nerve. Much of Jackson’s interior monologue is carried over, and Harris has to find a way to make these passages work without feeling too on the nose. Of course she does, and her near-rational self-possession near the end is terrifying. Harris’ voice obtains a steady pitch that’s marked with a decaying sense of sanity and composure as she makes peace with the house “wanting” her. Horror cinema is filled with films about brittle women cracking under psychological distress, and Harris’ performance must be mentioned near the top of great examples of what that looks like, right next to Deborah Kerr in The Innocents, Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby, and Catherine Deneuve in Repulsion.

The Haunting is a horror film of implication, suggestion, and extraction, one that retains much of its power and strength because of these choices. Wise was right to leave as much unsaid and left off-screen as Jackson did, and it makes the speculation over the “truth” of the haunting all the better. This is the horror film as sophisticated literary adaptation.

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,