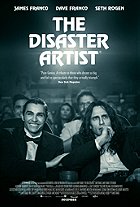

The Disaster Artist is pitched somewhere between star vanity project and reminder of what a gifted comedic actor it’s lead is, so think of it as something that encapsulates James Franco as a whole. It becomes something of an ego-stroking endeavor, as just about anything Franco touches inevitably does, and wants it both ways, to both laugh at and with its protagonist, but it’s still an accomplished little film in its own minor ways.

We hardly leave its main star, and if we do, it is to focus on Greg Sestero, played by Dave Franco, James’ younger brother. Yep, The Disaster Artist is both a family affair and an entertaining form of filmic masturbation as James Franco both pays tribute and parodies the making of a cult classic while clearly trying to pitch his own film as a ready for primetime player. It’s a tricky balancing act, and it’s not entirely one that comes off successfully by the end. The Disaster Artist has a parade of big name cameos that feel like favors called in at best, and at worst, like distractions from a narrative that’s gone routine.

Yet the relationship between the two men is one that’s fascinating when we’re allowed to merely sit back and watch it unfold. Sestero unironically finds Tommy Wiseau a magnetic and enthralling presence, and he’s not off the mark. For all of his questionable skill levels, Wiseau is a strangely hypnotic figure with his mane of greasy, unruly black hair, eternally heavy-lidded eyes, and accent that sounds like the Eastern Block by way of Burbank. If what Franco imagines Wiseau’s acting class exercise of the “Stella” monolog from A Streetcar Named Desire is true, it’s not an inaccurate summation of the piece in a skewed perspective. Even if it’s not true, it is still a wonderfully eccentric moment that makes us understand what Sestero sees in Wiseau that everyone else finds shocking, uncomfortable, or laughable.

But as the story goes on and we near the hellish production of The Room and the premiere, we find ourselves turning away from sympathetic feelings and more towards pointing and laughing. Wiseau is something of a tragic clown throughout, but the ending turns things a little too sour. There is something to be said for bad movies leaving as strong and lasting an impression as good ones, but The Disaster Artist isn’t smart enough to go there. It mainly wants to be a oneiric totem to James Franco the enervating artistic polymath, but it also reminds us that he’s best when sticking to comedy.

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,