If adversity and strife make for great art, then that perfectly explains why Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast is one of the towering greats of cinema. As the rubble and dust settled from WWII, Cocteau created this pristine and immaculate piece of fantasy cinema to rouse the collective spirit of the country, spurred on by the encouragements of his muse and lover Jean Marais. The film stock was hard to come by, causing certain scenes to look rougher than others were while maintaining the dream-like disorientation that permeates throughout. Cloth was harder to find, and several morning the crew and cast would go to set to find the bed sheets stolen overnight. And Jean Cocteau was gravely ill midway through production, and his condition required continuous breaks to take painful injections.

Now watch the film again and look for where the bleeding sutures from these tears in production show. You can’t find them, but you will find a movie of uncompromising beauty, grace, imagination, and poetry. Beauty and the Beast is equally soulful and fragile, ephemeral and tactile.

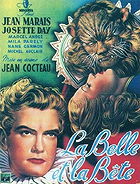

The film opens up with Cocteau, stars Jean Marais and Josette Day writing their names on a chalkboard, announcing a certain level of self-reflection and theater at play here. Then Cocteau breaks down the fourth wall further with a written prologue by imploring the audience directly to suspend their cynicism and open their minds to a child-like sense of belief and wonder. Beauty and the Beast is perhaps the most revealing and personal of Cocteau’s handful of films.

Cocteau was an artistic polymath, with a dizzying number of novels, poems, plays, librettos, drawings, and paintings created by him. He is best remembered for his films and this one in particular. By tapping into the sexuality in the fairy tale, and his own queerness in a roundabout way, Cocteau created the greatest film interpretation of a fairy tale and the definitive example of a monster-in-love.

The frustrations of repressed love are palpable in the Beast’s earliest interactions with Beauty. He carries her across the threshold, places her in her bed, and she recoils in terror when she first sees him. Humiliated, as he often will be in these early awkward romantic encounters, he turns from her and demands that she never look him in the eyes. These failed attempts at coitus come to a head when Beauty decides to take a stroll with the Beast in the woods, and the scene of him drinking from her hands is achingly romantic and erotically charged. Name me one queer kid who won’t identify with the abject terror Beauty and the Beast demonstrates in its earlier scenes at burgeoning sexuality and its confusion (Beauty’s bed in Beast’s castle opens up its own sheets, and she flees in terror/horror before fainting).

Yet it wasn’t just his own queerness that Cocteau tapped into here, but the scarred psyche of all of France. Beauty’s home life, a wasting bourgeoisie with a dying patriarch and divided loyalty within its unit, can be read as writ large of France’s immediate national id in the wake of the Nazi Occupation. The happy ending of Beauty and the Beast doesn’t declare itself with a strong period, but a more wistful ellipsis. Beauty’s disappointment in the Beast’s transformation from leonine to handsome prince is unmistakable, and this ending while optimistic is not declarative or definitive in any way.

It taps into much of Cocteau’s work, a deep love of the artifice and aestheticism. Surface textures, ornate costuming, proudly arcane special effects, and a pervading sense of romanticism merge with the ways he contorts our expectations. We expect Beauty to be an ethereal creature, one defined by her goodness and self-sacrifice, but Josette Day plays her with subtler shadings. Day excavates a dancer’s grace in Beauty’s movements even when she performs mundane tasks, and a weakness that borders on the hermetic. She’s doomed to a life of servitude towards her vain sisters, ineffectual father, lout brother, and the aggressive romantic advances of his best friend (Jean Marais, in one of his three roles). Day’s transformation from this oppressed creature to romantic figure is startling when you think about the trajectory of the character, but she does it with tremendous ease that you never see her sweat.

But this is as much Jean Marais’ masterpiece as Cocteau’s, and Marais plays his triple role with grace and confidence. He’s a portrait of toxic masculine aggression as Avenant, the beautiful but morally and emotionally empty friend of her brother’s. He’s poised and regal as the handsome prince with his stiff body carriage and posh manners. Yet these two performances are mere adornments to his work as the Beast, one of cinema’s greatest and most essential performances. His Beast is eternally at war with the regal prince trapped inside and the predatory exterior. The makeup job on him is extraordinary, but it’s the way that it frames and highlights his eyes that truly makes it special. Marais’ eyes are his primary means of expression for a long time, along with his hands that frequently signal his suppressed rages or demonstrate an uncommon grace. Beauty and the Beast is made-up of several great artists bringing their highest operating levels to this project, and Marais’ gesticulations, wounded eyes, and erotic screen presence cannot be praised enough here.

And if Beauty and the Beast is best remembered for anything, it’s the never-ending cascade of surreal, painterly images of magical occurrences. The Blood of a Poet had a few of these, but nothing prepares for the transportive powers of Beauty and the Beast’s sequences. There’s the scene where Beauty cries diamonds, one where she emerges from a wall after putting on a magical glove, she floats above the ground in Beast’s castle, and in yet another her clothing transforms from plainclothes to an elaborate gown by entering a doorway. This is but a handful of them, and sights that are even more wondrous as the film goes on. I’m quite fond of the quick glance of spilled pearls creating an elaborate jewel in the Beast’s palm myself.

If only more fantasy films would borrow the lyrical, imaginative tone on display here. It never shies away from the darker elements at play in the fairy tale, and it takes great relish in examining what we desire and fear. It’s romantic, it’s mature in its emotional life, it has an indomitable ability to make the fantastical feel as real as the poverty of its earliest scenes. Fuck Disney, Beauty and the Beast is the definitive film document of a fairy tale, and as close to cinematic nirvana as we can get.

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,