Is Interstellar truly worthy of the high star rating I have given it? Probably not, but goddamn if I didn’t admire its grand ambition, tremendous heart, and stellar acting ensemble enough to forgive its flaws. I happily went along its epic scope and large heart.

Taking place in a future where the present is beginning to look an awful lot like the Dust Bowl on a larger scale, we meet Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), a former NASA pilot forced into becoming a farmer. Farming is about all that currently happens on earth, despite massive amounts of crops dying out. Cooper is widowed and lives with his two children and their grandfather (John Lithgow), spending most of his days nurturing his daughter’s scientific curiosity and helping his son learning the farming trade. It’s not exactly a picturesque ideal, but it’s closest thing to a happy portrait of Americana that we’re allowed.

Through a strange series of circumstances, Cooper and his daughter, Murph (Mackenzie Foy as a child, Jessica Chastian as an adult and both fabulous), stumble upon what little remains of NASA and a secret project to find a new hospitable planet for the human race. Cooper must choose between abandoning his family and saving the planet, or sticking things out and watching everything die. Since the movie is three hours in length, and this is but the third act, it’s not a spoiler to say that he takes his chances in space.

It is here at NASA we meet regular Nolan player Michael Caine, this time as Professor Brand, a genius physicist, and his daughter Amelia (Anne Hathaway), a no-less brilliant scientist in her respective field. We will spend a great deal of time with McConaughey and Hathaway, depending on your tolerance for these actors, Interstellar is either going to be rough going or an enjoyable ride. I, clearly, found it quite enjoyable.

It was at some point last year when I turned the corner on McConaughey. It could have been his committed and better-than-the-surrounding-film performance in Dallas Buyers Club or the one-day marathon of True Detective’s first season that did it, probably both, but his work here is no less revelatory. His character is a split between wanting to explore and discover, and a fatherly need to return to those that love and need him. A scene in which he discovers a backlog of video transmissions from home is an emotional gut punch thanks to McConaughey’s smart acting choices.

I’ve long defended Hathaway, and I find much of the criticism against her rooted in some vaguely hinted sexism that demands that actresses not exhibit any kind of manic glee in career-changing milestones or exhibiting intellectualism instead of dumbing down and going for “they’re just like us!” artifice. Her previous work with Nolan resulted in her tremendously fun take on Catwoman in The Dark Knight Rises, asking her to play a 40s femme fatale and a sardonic grifter with equal weight. Her role here is a little underwritten in parts, but she’s strong enough to give it a gravity and weight that overcomes this obstacle.

The leads find the perfect balance that the rest of the film lacks. That is to say, McConaughey and Hathaway have found a way to make the big ideas and big heart merge into a coherent picture, whereas the rest of Interstellar sometimes dips too far one way or another. But I appreciate that it went for such grand pronouncements, it overreaches often, but I’m a big softie for something that tries and nearly succeeds more often than not and reward tons of points for trying.

Interstellar does however suffer from a similar problem as the rest of Nolan’s work – over explaining and re-explaining things over and over again. At times, this is necessary to understand and grasp the scientific concepts on display here. Most of the time it reintroduces characters and what they’re symbolic of or their position when this is not needed. I think of how Batman Begins played so heavily on repeating “fear” as a subtext and theme that it stopped being both (I still enjoy it greatly), or how The Prestige structured itself as the titular event and ended up being its own undoing. Nolan is a film-maker who likes to treat his films like strange puzzle boxes, explaining to us the rules, sometimes at the detriment to natural sounding dialog, but I don’t mind it. There’s room for all kinds of film-makers. And any director who takes a massive studio budget and crafts something this unique, ambitious, messy, interesting, sweeping, and personal is one that I will follow on any storytelling diversion he chooses.

Interstellar

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 29 December 2014 10:33

(A review of Interstellar)

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 29 December 2014 10:33

(A review of Interstellar) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

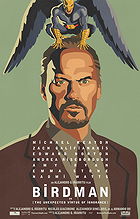

Birdman (or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 29 December 2014 10:32

(A review of Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance))

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 29 December 2014 10:32

(A review of Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance))I am prepared to be one of the lone dissenting voices on Birdman’s inevitable domination come awards season. Just looking at the critical consensus at Rotten Tomatoes means I am in the 7% who did not find the movie “an ambitious technical showcase powered by a layered story.”

No, I found Birdman to be contemptuous of its audience, assaulting their intelligence and talking down to them in loudly delivered bullet points without much development or original thought behind them. It hides behind this well-traveled and overly familiar terrain with two fantastic leading performances, a great under-utilized one, and virtuosity that is frequently more distracting than it is awe-inspiring.

Made to look like one continuous take, Birdman tells the story of an actor on the brink of being completely forgotten taking a stab at a revitalization by writing, directing, and starring in a Broadway production of a Raymond Carver short story. The premise is strong, but then Alejandro González Iñárritu makes a series of decisions that are questionable at best. I have long been only mildly impressed with his work, but Birdman may have firmly tipped me into actively disliking him. But more on that later.

Where Birdman is very strong is in the central performance from Michael Keaton. I may have disliked the film, but I am completely enamored with his strong work here. Granted, casting him as a potentially washed up actor most known for his superhero films at first feels like a bit of cheap stunt casting, but Keaton’s always been an underrated talent and he creates something more interesting and vital with his performance here. One of Keaton’s great strengths as an actor, and it is indulged here, is his ability to project paranoia and a manic energy into his characters. His best creations always feel like they’re slowly dancing upon the edge of sanity and pure madness, and that works like gangbusters here. It may be too soon to call a likely candidate to sweep Best Actor, but I just really loved Keaton’s work enough to hope it makes it to the podium come Oscar night.

The other two performances that I quite enjoyed were Edward Norton as a primadonna actor and Emma Stone as Keaton’s drug addict daughter/assistant, I hope both of them will be nominated in the supporting categories at this year’s Oscar ceremony. Norton gets the bigger role, and he plays it for all the crazed, darkly comic pathos that is available. Stone, somewhat wasted in an underwritten role, makes a notable impression with what little she has been given to do. I wanted more from her here.

But that’s about all of the praise I have for Birdman. The rest is a serious of loud sloganeering delivered as if it was kind of deep philosophical thought on the state of art in America. And a theater critic is a badly written artifice, a creation of purely malevolence intent that only wants to see Keaton fail for no real reason other than he’s a Hollywood actor who dares to go to Broadway. Birdman’s got some strange ideas, antiquated ones, about what constitutes true art and what is only pretending. A more serious discussion would have been much preferable to various characters talking AT the critic. Instead from the moment she is introduced we are aware that unless some kind of miracle happens, she’s going to pan the show.

But this juvenile approach to artistic criticism, a true necessity if one is to grow in any way, shape or form, as simply “haters gon’ hate” isn’t the worst of the film’s problems. Worse yet is the fast and loose treatment of magic realism. Much of the film details fantastical flights of imagination that are revealed to have only been the thoughts of Keaton’s slowly crumbling actor. That is, until we get to the very last moments of the film in which is suddenly wants to tell us that all of those flights of fancy are true. This is despite the film undercutting them every time previously. I don’t mind a film making me question whether or not the magic was real, as long as it plays fair with the rules created within its world. Pan’s Labyrinth and Black Swan both played fair, Birdman was more interesting when those fantasies were the products of a person’s mental collapse.

As for Alejandro González Iñárritu? To play devil’s advocate, I have not seen Biutiful, but I have seen 21 Grams and Babel. I found both of them to be films of strange choices that undercut the material. 21 Grams decision to needlessly convolute the timeline destroyed any mounting dread or emotional involvement, reducing the drama to series of depressing tableaus that would have been much better if delivered straight. While Babel was another Crash, but this time on a global scale. Everything is connected, glamorous movie stars suffering, everything wrapped up in Academy-friendly packaging and nothing much of interest to say. Thank god, they went with The Departed that year instead. This film is just the latest his self-serious, didactic oeuvre. He has grand ambition, but he can’t seem to find the correct tone or pitch in any of these. Yet the finished product still feels intellectually smug and pretentious. Thanks be to Keaton for being a combustible element in this wet blanket.

No, I found Birdman to be contemptuous of its audience, assaulting their intelligence and talking down to them in loudly delivered bullet points without much development or original thought behind them. It hides behind this well-traveled and overly familiar terrain with two fantastic leading performances, a great under-utilized one, and virtuosity that is frequently more distracting than it is awe-inspiring.

Made to look like one continuous take, Birdman tells the story of an actor on the brink of being completely forgotten taking a stab at a revitalization by writing, directing, and starring in a Broadway production of a Raymond Carver short story. The premise is strong, but then Alejandro González Iñárritu makes a series of decisions that are questionable at best. I have long been only mildly impressed with his work, but Birdman may have firmly tipped me into actively disliking him. But more on that later.

Where Birdman is very strong is in the central performance from Michael Keaton. I may have disliked the film, but I am completely enamored with his strong work here. Granted, casting him as a potentially washed up actor most known for his superhero films at first feels like a bit of cheap stunt casting, but Keaton’s always been an underrated talent and he creates something more interesting and vital with his performance here. One of Keaton’s great strengths as an actor, and it is indulged here, is his ability to project paranoia and a manic energy into his characters. His best creations always feel like they’re slowly dancing upon the edge of sanity and pure madness, and that works like gangbusters here. It may be too soon to call a likely candidate to sweep Best Actor, but I just really loved Keaton’s work enough to hope it makes it to the podium come Oscar night.

The other two performances that I quite enjoyed were Edward Norton as a primadonna actor and Emma Stone as Keaton’s drug addict daughter/assistant, I hope both of them will be nominated in the supporting categories at this year’s Oscar ceremony. Norton gets the bigger role, and he plays it for all the crazed, darkly comic pathos that is available. Stone, somewhat wasted in an underwritten role, makes a notable impression with what little she has been given to do. I wanted more from her here.

But that’s about all of the praise I have for Birdman. The rest is a serious of loud sloganeering delivered as if it was kind of deep philosophical thought on the state of art in America. And a theater critic is a badly written artifice, a creation of purely malevolence intent that only wants to see Keaton fail for no real reason other than he’s a Hollywood actor who dares to go to Broadway. Birdman’s got some strange ideas, antiquated ones, about what constitutes true art and what is only pretending. A more serious discussion would have been much preferable to various characters talking AT the critic. Instead from the moment she is introduced we are aware that unless some kind of miracle happens, she’s going to pan the show.

But this juvenile approach to artistic criticism, a true necessity if one is to grow in any way, shape or form, as simply “haters gon’ hate” isn’t the worst of the film’s problems. Worse yet is the fast and loose treatment of magic realism. Much of the film details fantastical flights of imagination that are revealed to have only been the thoughts of Keaton’s slowly crumbling actor. That is, until we get to the very last moments of the film in which is suddenly wants to tell us that all of those flights of fancy are true. This is despite the film undercutting them every time previously. I don’t mind a film making me question whether or not the magic was real, as long as it plays fair with the rules created within its world. Pan’s Labyrinth and Black Swan both played fair, Birdman was more interesting when those fantasies were the products of a person’s mental collapse.

As for Alejandro González Iñárritu? To play devil’s advocate, I have not seen Biutiful, but I have seen 21 Grams and Babel. I found both of them to be films of strange choices that undercut the material. 21 Grams decision to needlessly convolute the timeline destroyed any mounting dread or emotional involvement, reducing the drama to series of depressing tableaus that would have been much better if delivered straight. While Babel was another Crash, but this time on a global scale. Everything is connected, glamorous movie stars suffering, everything wrapped up in Academy-friendly packaging and nothing much of interest to say. Thank god, they went with The Departed that year instead. This film is just the latest his self-serious, didactic oeuvre. He has grand ambition, but he can’t seem to find the correct tone or pitch in any of these. Yet the finished product still feels intellectually smug and pretentious. Thanks be to Keaton for being a combustible element in this wet blanket.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

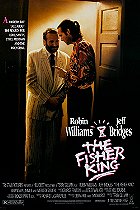

The Fisher King

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 28 December 2014 02:26

(A review of The Fisher King)

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 28 December 2014 02:26

(A review of The Fisher King)Ambitious enough for several films, and sometimes it feels like three of them stitched together at times, The Fisher King may just be Terry Gilliam’s greatest film, Brazil is a strong(er) contender in my opinion. The Fisher King gives us so much to consider: the homeless, mental illness, redemption, Arthurian legend, show-biz, two love affairs, comedy. Somehow, I found it all working together and emerging as a unique, moving experience, with solid performances from the four major leads – Jeff Bridges, Mercedes Ruehl, Amanda Plummer, and Robin Williams, towering above them all with his beautiful and intricate work.

The Fisher King tells of the story of Jeff Bridges’ shock-jock radio personality who discovers one day that a listener has gone on a shooting spree, apparently taking his braggadocio to heart. Utterly devastated by the events, he quits his job, and finds himself living with Ruehl and working in her video rental store. Along the way he meets Williams, a homeless man, who is the key to his redemption. But first, Bridges and Ruehl trying to get Williams’ life back on track and set him up with Plummer, the woman he has been lusting after from afar for a while now.

Whew! That’s only the half of it. We haven’t even covered Williams’ tragic past, how it intersects with Bridges, or how his character is obsessed with the Holy Grail and believes it to be located in the mansion of a Manhattan gazillionaire. Or how he recruits Bridges to try and help him steal it. Or even the tortured hallucinations that he frequently lapses into. The Fisher King is overflowing with plot and character development, but it is also a (mostly) hilarious ride and enchanting to the last. It’s dramatic moments are hard-earned, and any bit of emotional movement and uplift we feel is made the better because these characters are battle-scarred and deserve a happy moment.

While Bridges and Plummer deliver typically strong work, the film truly belongs to the performances of Ruehl and Williams. Mercedes Ruehl, at the time, was the go-to character actress for strong, tough-talking dames. Her work here has that element on the surface, but there’s also a tragic underside to her character, a woman in dire need of love and acceptance, and not finding it in her chosen partner. There’s a scene in which her character begins to crack up, talking to herself, alternating between laughter and tears, growing resentful of Bridges standing her up and disappointing her once more. It’s a lovely piece of work in a rich performance, and probably the scene that helped nab her every imaginable Supporting Actress award that year.

Yet it’s Williams as the homeless Parry who lingers longest in the mind. It’s often been said that the best performances have something of the performers truth in them. It would be simple to write off The Fisher King’s strong work as something so simple in the wake of Williams’ suicide, but his manic impressions and damaged core ring truer than most of the soulful comics he played in films like Good Morning, Vietnam and Dead Poets Society. It’s not right to compare actors to their characters, but sometimes a performer and a role meet and a little bit of the real person spills out into the one that they’re constructing. That could easily be the case here. A scene where Williams experiences happiness, gets frightened, and runs from the flaming Red Knight (the film’s literal manifestation of his mental illness and trauma), only to encounter three men ready to beat him up only to thank them feels dreadfully resonant and real in the wake of real life events, more so than it would originally have. Williams was nominated for, but lost, the Oscar that year, and while he went on to win one for his equally great work in Good Will Hunting, I feel as if his work here is the true mark to his brilliance as an actor. The role allows him to fluctuate between comedy and drama seamlessly, reigning in some of his manic tendencies when necessary, and letting him off the leash in service of the role when necessary.

The Fisher King tells of the story of Jeff Bridges’ shock-jock radio personality who discovers one day that a listener has gone on a shooting spree, apparently taking his braggadocio to heart. Utterly devastated by the events, he quits his job, and finds himself living with Ruehl and working in her video rental store. Along the way he meets Williams, a homeless man, who is the key to his redemption. But first, Bridges and Ruehl trying to get Williams’ life back on track and set him up with Plummer, the woman he has been lusting after from afar for a while now.

Whew! That’s only the half of it. We haven’t even covered Williams’ tragic past, how it intersects with Bridges, or how his character is obsessed with the Holy Grail and believes it to be located in the mansion of a Manhattan gazillionaire. Or how he recruits Bridges to try and help him steal it. Or even the tortured hallucinations that he frequently lapses into. The Fisher King is overflowing with plot and character development, but it is also a (mostly) hilarious ride and enchanting to the last. It’s dramatic moments are hard-earned, and any bit of emotional movement and uplift we feel is made the better because these characters are battle-scarred and deserve a happy moment.

While Bridges and Plummer deliver typically strong work, the film truly belongs to the performances of Ruehl and Williams. Mercedes Ruehl, at the time, was the go-to character actress for strong, tough-talking dames. Her work here has that element on the surface, but there’s also a tragic underside to her character, a woman in dire need of love and acceptance, and not finding it in her chosen partner. There’s a scene in which her character begins to crack up, talking to herself, alternating between laughter and tears, growing resentful of Bridges standing her up and disappointing her once more. It’s a lovely piece of work in a rich performance, and probably the scene that helped nab her every imaginable Supporting Actress award that year.

Yet it’s Williams as the homeless Parry who lingers longest in the mind. It’s often been said that the best performances have something of the performers truth in them. It would be simple to write off The Fisher King’s strong work as something so simple in the wake of Williams’ suicide, but his manic impressions and damaged core ring truer than most of the soulful comics he played in films like Good Morning, Vietnam and Dead Poets Society. It’s not right to compare actors to their characters, but sometimes a performer and a role meet and a little bit of the real person spills out into the one that they’re constructing. That could easily be the case here. A scene where Williams experiences happiness, gets frightened, and runs from the flaming Red Knight (the film’s literal manifestation of his mental illness and trauma), only to encounter three men ready to beat him up only to thank them feels dreadfully resonant and real in the wake of real life events, more so than it would originally have. Williams was nominated for, but lost, the Oscar that year, and while he went on to win one for his equally great work in Good Will Hunting, I feel as if his work here is the true mark to his brilliance as an actor. The role allows him to fluctuate between comedy and drama seamlessly, reigning in some of his manic tendencies when necessary, and letting him off the leash in service of the role when necessary.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

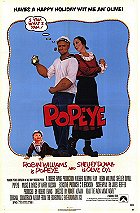

Popeye

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 28 December 2014 02:26

(A review of Popeye)

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 28 December 2014 02:26

(A review of Popeye)Perhaps if I had grown up watching this movie as a child, I would have become part of the large cult demanding that this movie be placed within the pantheon of great films from Robert Altman. It doesn’t belong there, hell, it doesn’t even really belong in his second-tier of films. Yet there’s still something enchanting about its ambitious nature despite its repeated failures to even out in tone.

Much of the minor successes of the film belong to the ingenious, frequently obvious, choices in casting. Robin Williams playing a live-action cartoon character? That seems like a no brainer decision, even for Williams’ first film role. And he gives his Julliard-trained best to animating a live action Popeye, perfectly mimicking the muffled, teeth-gritted speech patterns and hunched, propulsive way of walking. Shelley Duvall, Paul Dooley, Paul L. Smith all feel like the cartoon creations brought into the real world. Duvall’s big saucer eyes and nervous energy in particular are a perfect fit for the character.

And the entire production design, costumes, makeup, and cheesy practical effects are effortlessly charming. The main problem with Popeye is in the insistence that it be made into a musical, and a children’s film, neither of which are Altman’s strongest points of view as an artist. There isn’t a memorable musical number throughout the entire film, and many of these sequences lack energy or coherence. Altman’s over-lapping dialog works for his mass ensemble dramas, but not for a musical aimed at family audiences. What emerges is an awkward film, one that is by turns charming, sometimes deadly dull. It’s an odd marriage of Altman’s cynicism beating against the sunny shores of the Fleischer cartoons it owes its origins too (it bears little-to-no resemblance to the comic strips). But it is refreshing to see something darker, more ambitious than the normal Disney simplification of good-and-evil’s eternal struggle.

Much of the minor successes of the film belong to the ingenious, frequently obvious, choices in casting. Robin Williams playing a live-action cartoon character? That seems like a no brainer decision, even for Williams’ first film role. And he gives his Julliard-trained best to animating a live action Popeye, perfectly mimicking the muffled, teeth-gritted speech patterns and hunched, propulsive way of walking. Shelley Duvall, Paul Dooley, Paul L. Smith all feel like the cartoon creations brought into the real world. Duvall’s big saucer eyes and nervous energy in particular are a perfect fit for the character.

And the entire production design, costumes, makeup, and cheesy practical effects are effortlessly charming. The main problem with Popeye is in the insistence that it be made into a musical, and a children’s film, neither of which are Altman’s strongest points of view as an artist. There isn’t a memorable musical number throughout the entire film, and many of these sequences lack energy or coherence. Altman’s over-lapping dialog works for his mass ensemble dramas, but not for a musical aimed at family audiences. What emerges is an awkward film, one that is by turns charming, sometimes deadly dull. It’s an odd marriage of Altman’s cynicism beating against the sunny shores of the Fleischer cartoons it owes its origins too (it bears little-to-no resemblance to the comic strips). But it is refreshing to see something darker, more ambitious than the normal Disney simplification of good-and-evil’s eternal struggle.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Three Little Pigskins

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 20 December 2014 05:13

(A review of Three Little Pigskins)

Posted : 10 years, 6 months ago on 20 December 2014 05:13

(A review of Three Little Pigskins)A moment of discretion before I begin, I've never been much of a fan of the Three Stooges. Even as a kid I couldn't vibe with their slower pace and low boiling anarchy. Give me the Looney Tunes, Laurel & Hardy, or Marx Brothers over them any day.

So it should go without saying that I came to "Three Little Pigskins" mostly to watch a young Lucille Ball first, and the Stooges as a secondary reason. I didn't hate it, but I didn't enjoy it much. It's slowly paced, and the jokes are very obvious. Compared to free-for-all madcap insanity of Horse Feathers, this short cannot compare. The Three Stooges are recruited to drum up interest for a university's football team, get mistaken for high-profile players by three attractive women, and drafted into playing a game in the last few minutes. It's all just kind of there, never really igniting or launching a rapid succession of successful bits.

So it should go without saying that I came to "Three Little Pigskins" mostly to watch a young Lucille Ball first, and the Stooges as a secondary reason. I didn't hate it, but I didn't enjoy it much. It's slowly paced, and the jokes are very obvious. Compared to free-for-all madcap insanity of Horse Feathers, this short cannot compare. The Three Stooges are recruited to drum up interest for a university's football team, get mistaken for high-profile players by three attractive women, and drafted into playing a game in the last few minutes. It's all just kind of there, never really igniting or launching a rapid succession of successful bits.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Road

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 26 November 2014 02:19

(A review of The Road (2009))

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 26 November 2014 02:19

(A review of The Road (2009))Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is a devastating look at life after the destruction and collapse of organized civilization, and a moving look at the lengths one father will go towards keeping his son safe. Told with the simplicity and power of Biblical language, the novel is alternately profoundly moving and emotionally gutting, violent yet hopeful. The film version is well-made, well acted, and looks like what one would imagine as you read the text, yet it’s missing that brutal poetry of McCarthy’s language.

The film version of The Road is case of an adaptation doing everything right, but still missing that extra spark to make it really ignite. McCarthy’s prose is deceptively simple, a muscular beast that brings to mind both the language of the church and Faulkner’s Southern Gothic cadences. No film can truly capture it, and The Road thrives upon it. But this version of the story adequate itself as best it can.

Director John Hillcoat moves the material along efficiently, making a few omissions of scenes of great depravity or disturbing findings. He creates a world in which life is quickly swirling the drain, and the roving bands of cannibals hidden amongst the ash and dwindling supplies loom largely as a new kind of all too real boogeyman. And he casts the two lead roles perfectly, Viggo Mortensen is stubborn survivalism and dogged determination to survive and protect his son. While Kodi Smit-McPhee plays the son, a character that is both strangely naïve and innocent yet highly aware that death lurks around every corner and could overtake them at any moment.

Charlize Theron, Robert Duvall, and Guy Pearce appear in small supporting parts. The primary focus of The Road is on the father and son journeying towards the sea, no reason is given other than we’ve been taught that we’re supposed to go to the ocean, driving their by pioneering spirit and vague concepts like Manifest Destiny. Theron is the wife and mother of these characters, a woman who could no longer live in this world and chose to walk towards her fate one night, leaving them both behind. Duvall appears briefly in one extended scene as a blind elderly man they encounter, and Guy Pearce as a family man at the climax. These roles amount to little more than extended cameos, and occasionally feel like distractions. Why not just get unknown actors for such small parts, or were they needed to help finance the film?

I admit it, there’s a cardinal sin in reviewing a movie based on a book in how well it captures the book. An adaptation must take the essence and main points of the novel, remodel them to work in a new media, and have an artistic point-of-view. Demanding that a film be married to the text is a fools journey, and perhaps some of my reservations about The Road as a film are in direct contrast with my love for McCarthy’s writing. The film is great, but the novel has power that is more emotional. Could there have been a way for the film-makers to capture that power in the film? Perhaps, but perhaps McCarthy’s prose style is too acutely suited for the page and not the screen to correctly translate.

The film version of The Road is case of an adaptation doing everything right, but still missing that extra spark to make it really ignite. McCarthy’s prose is deceptively simple, a muscular beast that brings to mind both the language of the church and Faulkner’s Southern Gothic cadences. No film can truly capture it, and The Road thrives upon it. But this version of the story adequate itself as best it can.

Director John Hillcoat moves the material along efficiently, making a few omissions of scenes of great depravity or disturbing findings. He creates a world in which life is quickly swirling the drain, and the roving bands of cannibals hidden amongst the ash and dwindling supplies loom largely as a new kind of all too real boogeyman. And he casts the two lead roles perfectly, Viggo Mortensen is stubborn survivalism and dogged determination to survive and protect his son. While Kodi Smit-McPhee plays the son, a character that is both strangely naïve and innocent yet highly aware that death lurks around every corner and could overtake them at any moment.

Charlize Theron, Robert Duvall, and Guy Pearce appear in small supporting parts. The primary focus of The Road is on the father and son journeying towards the sea, no reason is given other than we’ve been taught that we’re supposed to go to the ocean, driving their by pioneering spirit and vague concepts like Manifest Destiny. Theron is the wife and mother of these characters, a woman who could no longer live in this world and chose to walk towards her fate one night, leaving them both behind. Duvall appears briefly in one extended scene as a blind elderly man they encounter, and Guy Pearce as a family man at the climax. These roles amount to little more than extended cameos, and occasionally feel like distractions. Why not just get unknown actors for such small parts, or were they needed to help finance the film?

I admit it, there’s a cardinal sin in reviewing a movie based on a book in how well it captures the book. An adaptation must take the essence and main points of the novel, remodel them to work in a new media, and have an artistic point-of-view. Demanding that a film be married to the text is a fools journey, and perhaps some of my reservations about The Road as a film are in direct contrast with my love for McCarthy’s writing. The film is great, but the novel has power that is more emotional. Could there have been a way for the film-makers to capture that power in the film? Perhaps, but perhaps McCarthy’s prose style is too acutely suited for the page and not the screen to correctly translate.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Traffic

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 26 November 2014 02:19

(A review of Traffic)

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 26 November 2014 02:19

(A review of Traffic)Traffic takes a look at the War on Drugs through a prismatic lens – focusing equally at their source, the public, federal government, and the U.S. border. Some stories are more interesting than others are, and the entire film is awash in needlessly artsy cinematography. Each story has its own distinct look and color scheme, frequently washed or bleached out and layered over with a colored filter.

Thankfully, Traffic presents these various stories with an even hand and refrains from the typically Hollywood choice of blustery editorializing. Addiction is a health issue – physical, emotional, mental – and shouldn’t be treated like a crime. I’ve long believed this given my own history and complicated personal relationships, and it’s nice to see a film which treats the issue as such. At least, as far as the story about a U.S. politician’s daughter descent into crack-cocaine addiction and self-destruction goes. That’s one is good, even better is the pregnant housewife of luxury that sees her entire world turn upside down once it’s revealed that her husband is a high-level drug dealer. She turn from sheltered housewife to avenging queen of a cartel is a shocking display of fight-or-flight through a warped filter.

Traffic is built upon multiple stories that frequently don’t connect directly but connect spiritually. Some are more engaging than others, but all of them are filled with a brilliant ensemble of great actors doing commendable work. Benicio del Toro gets a flashy role as a Mexican cop playing several sides, and he gives it his gonzo all. He won all the applause and awards at the time, but the role that the film rests upon is Michael Douglas’ conflicted U.S. politician. He must travel smoothly from righteous indignation about the entire abstract concept and realities of drug use in America to a more understanding and grey area as it arrives upon his doorstep.

Thankfully, Traffic presents these various stories with an even hand and refrains from the typically Hollywood choice of blustery editorializing. Addiction is a health issue – physical, emotional, mental – and shouldn’t be treated like a crime. I’ve long believed this given my own history and complicated personal relationships, and it’s nice to see a film which treats the issue as such. At least, as far as the story about a U.S. politician’s daughter descent into crack-cocaine addiction and self-destruction goes. That’s one is good, even better is the pregnant housewife of luxury that sees her entire world turn upside down once it’s revealed that her husband is a high-level drug dealer. She turn from sheltered housewife to avenging queen of a cartel is a shocking display of fight-or-flight through a warped filter.

Traffic is built upon multiple stories that frequently don’t connect directly but connect spiritually. Some are more engaging than others, but all of them are filled with a brilliant ensemble of great actors doing commendable work. Benicio del Toro gets a flashy role as a Mexican cop playing several sides, and he gives it his gonzo all. He won all the applause and awards at the time, but the role that the film rests upon is Michael Douglas’ conflicted U.S. politician. He must travel smoothly from righteous indignation about the entire abstract concept and realities of drug use in America to a more understanding and grey area as it arrives upon his doorstep.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Easy Rider

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 26 November 2014 02:19

(A review of Easy Rider)

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 26 November 2014 02:19

(A review of Easy Rider)I don’t mean this in a snide or mean-spirited way, in fact this isn’t a criticism at all, but Easy Rider is like an encapsulation of the late 60s counter-cultural movement played out in microcosm. A pure distillation of the concerns, thoughts, and bacchanal of that generation’s ennui played out across the road. What exactly are Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper looking for in Easy Rider? Who knows for certain, but what they find is a portrait of an American filled with rot and sickness.

Tangentially, Fonda and Hopper are trafficking drugs from Los Angeles to New Orleans, but the film takes many detours away from this main plot, dabbling in existentialism and an encroaching dread. It came out around the time of Woodstock, but something about Easy Rider’s minimalist dialog, wandering eye for scenery, and heavy use of destructive symbolize to telegraph the ending play like a warm-up for the destruction of the very movement it’s capturing.

I’m not entirely sure if Easy Rider plays today as living cinema the way a film like Bonnie & Clyde still does, or if it plays out as a moving historical diagram of the period. No matter, few films feel as authentically lived in and observed. Hopper and Fonda are rightly considered iconographic figureheads of the era and culture this film dictates, and that was before Easy Rider cemented them into the public consciousness as such. Once you add in New Hollywood mainstays like Karen Black and Jack Nicholson in some of their first major roles, then Easy Rider deserves its classic status tenfold.

Granted, not every segment in Rider is an absolute winner. An extended stay at a hippie commune is alternately banal and a strange sidetrack. Much better is when Jack Nicholson’s alcoholic lawyer appears, and everything congeals into a satisfying and coherent whole. He gives them the information about a brothel in New Orleans, which will come into play later as an acid trip with two hookers in a cemetery turns sour. We’ve been spiraling towards an unhappy ending throughout, and this sequence only solidifies that dark creeping feeling. Looking at it now, it’s as if Hopper and Fonda stared into their generations dreams, the American ideal that their parents fed them, and found only a destructive energy, an unstable force barely holding together several institutions that were ready to crumble at a moment’s notice. “We blew it, man.” What he meant then and how it plays now are two vastly different things.

Tangentially, Fonda and Hopper are trafficking drugs from Los Angeles to New Orleans, but the film takes many detours away from this main plot, dabbling in existentialism and an encroaching dread. It came out around the time of Woodstock, but something about Easy Rider’s minimalist dialog, wandering eye for scenery, and heavy use of destructive symbolize to telegraph the ending play like a warm-up for the destruction of the very movement it’s capturing.

I’m not entirely sure if Easy Rider plays today as living cinema the way a film like Bonnie & Clyde still does, or if it plays out as a moving historical diagram of the period. No matter, few films feel as authentically lived in and observed. Hopper and Fonda are rightly considered iconographic figureheads of the era and culture this film dictates, and that was before Easy Rider cemented them into the public consciousness as such. Once you add in New Hollywood mainstays like Karen Black and Jack Nicholson in some of their first major roles, then Easy Rider deserves its classic status tenfold.

Granted, not every segment in Rider is an absolute winner. An extended stay at a hippie commune is alternately banal and a strange sidetrack. Much better is when Jack Nicholson’s alcoholic lawyer appears, and everything congeals into a satisfying and coherent whole. He gives them the information about a brothel in New Orleans, which will come into play later as an acid trip with two hookers in a cemetery turns sour. We’ve been spiraling towards an unhappy ending throughout, and this sequence only solidifies that dark creeping feeling. Looking at it now, it’s as if Hopper and Fonda stared into their generations dreams, the American ideal that their parents fed them, and found only a destructive energy, an unstable force barely holding together several institutions that were ready to crumble at a moment’s notice. “We blew it, man.” What he meant then and how it plays now are two vastly different things.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Safety Not Guaranteed

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 25 November 2014 01:49

(A review of Safety Not Guaranteed)

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 25 November 2014 01:49

(A review of Safety Not Guaranteed)Safety Not Guaranteed is one of those blandly smug indie films that suddenly turn cloyingly earnest in the end, wanting to play it both ways. Granted, I found some of the tone and treatment of Mark Duplass’s character to be generally questionable throughout, turning him from a deeply emotionally damaged man to just a quirky eccentric by the end being the main offender. But damn if I didn’t stick it out for Aubrey Plaza’s pleasingly acerbic and tender lead performance.

Perhaps my biggest problem with Safety Not Guaranteed is that ending, which tosses out the main thrust of the film up to that point: “You can’t go back.” As the film neared its conclusion I began to have a sinking feeling in my stomach that they were going to abandon everything they had built up to that point and make the time travel actually work. They did, and I think the film’s easy out of a happy ending was a betrayal of the emotionally grounded narrative up to that point. But is it really a happy ending? There’s a brighter future standing in front of them, but they can’t see past their specific hurts to acknowledge that.

Perhaps my biggest problem with Safety Not Guaranteed is that ending, which tosses out the main thrust of the film up to that point: “You can’t go back.” As the film neared its conclusion I began to have a sinking feeling in my stomach that they were going to abandon everything they had built up to that point and make the time travel actually work. They did, and I think the film’s easy out of a happy ending was a betrayal of the emotionally grounded narrative up to that point. But is it really a happy ending? There’s a brighter future standing in front of them, but they can’t see past their specific hurts to acknowledge that.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Capote

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 25 November 2014 01:15

(A review of Capote (2005))

Posted : 10 years, 7 months ago on 25 November 2014 01:15

(A review of Capote (2005))There are many ways to tackle a celebrity biographical film, typically they lean hard on the “greatest hits” approach, presenting a series of vignettes that don’t add up to a complete portrait or point-of-view as to why this artist mattered. Instead these films gloss over everything that went into crafting their public image or artistry, presenting a canonized portrait of the persona, one in which they seemed to spring fully formed from the ephemera of the culture of their time in order to move things forward. These films are tedious, and the examples of them too numerous to mention, far better are the films which zero in on one specific moment and use it to explore why this person mattered.

Capote focuses in on the titular author’s decision to take a grisly murder story he read in the newspaper, and write a book about, crafting an entirely new genre of writing in the process, while simultaneously destroying his creative muse in the process. In a sense, Capote sees both the birth of a legendary work and the moment that lead to the decades long demise of his artistic output, becoming a jet set member and frequent bon vivant on talk show appearances. The seeds of the latter are sprinkled throughout the film, while the former is the driving force of the film.

Truman Capote’s life is made up of such moments that could be made into arresting and engaging films, but it makes sense to focus in on the creation of In Cold Blood. A manageable four year period of time, which saw him go from an author of respected short stories and novels to a literary lion and white-hot celebrity, birthing the non-fiction book in the process, and the film uses this entry point to explore the complicated psychosis of the troubled writer.

Seeing a news item and a chance to create a portrait of a town dealing with tragedy, Capote’s ambitions get the better of him, driving him inextricably towards Holcomb, Kansas. For Capote, this town would grow to become the location of his eventually undoing, as he grows closer and closer to the two murders, one of whom in particular could be described as something of a (twisted) soul mate or kindred spirit. The contradiction of falling in love with one of the killers while needing them to die to create a satisfying conclusion to his book highlights the viciousness of Capote’s ambitions while also planting the seeds of alcoholic destruction and complete avoidance of his artistic craft. The film slowly shows us the broken, destructive core, a man of great narcissism, underneath the mask of a charming, impish wit and social butterfly.

The (late) great Philip Seymour Hoffman’s essay of Capote is not an easy bit of copying mannerisms and resting on obvious twitches of a public persona. Hoffman digs deeper than normal, revealing the self-hatred in quiet moments when Capote realizes he has fallen in love with the killer while also waiting for him to die. A telling exchange occurs between him and his best friend, Harper Lee (a magnificently understated and warm Catherine Keener), where he says that there was nothing he could do to save them, and she responds with “Maybe, but the fact is that you didn’t want to.” Lee is the only character in the film who sees Capote for who he truly is, and she telegraphs it often.

Scenes of Capote gad flying about town with the rich and famous, poking fun at the rubes he’s documenting, then returning to Kansas and charming them with stories of the glitterati and movie stars display his contradictions. If one knows anything about his life, one knows that Capote’s childhood was marked by loneliness and abandonment, his public face a carefully cultivated persona to get love and attention from whoever was present. These scenes reveal that neediness and sadness. While not always a flattering portrait, Capote is fair-handed in detailing both the good and bad of a real person. What makes the film work so well, and Hoffman’s performance so perfect, is how it stares Capote’s moral and artistic disintegration straight in the eye and never flinch for a moment.

Capote focuses in on the titular author’s decision to take a grisly murder story he read in the newspaper, and write a book about, crafting an entirely new genre of writing in the process, while simultaneously destroying his creative muse in the process. In a sense, Capote sees both the birth of a legendary work and the moment that lead to the decades long demise of his artistic output, becoming a jet set member and frequent bon vivant on talk show appearances. The seeds of the latter are sprinkled throughout the film, while the former is the driving force of the film.

Truman Capote’s life is made up of such moments that could be made into arresting and engaging films, but it makes sense to focus in on the creation of In Cold Blood. A manageable four year period of time, which saw him go from an author of respected short stories and novels to a literary lion and white-hot celebrity, birthing the non-fiction book in the process, and the film uses this entry point to explore the complicated psychosis of the troubled writer.

Seeing a news item and a chance to create a portrait of a town dealing with tragedy, Capote’s ambitions get the better of him, driving him inextricably towards Holcomb, Kansas. For Capote, this town would grow to become the location of his eventually undoing, as he grows closer and closer to the two murders, one of whom in particular could be described as something of a (twisted) soul mate or kindred spirit. The contradiction of falling in love with one of the killers while needing them to die to create a satisfying conclusion to his book highlights the viciousness of Capote’s ambitions while also planting the seeds of alcoholic destruction and complete avoidance of his artistic craft. The film slowly shows us the broken, destructive core, a man of great narcissism, underneath the mask of a charming, impish wit and social butterfly.

The (late) great Philip Seymour Hoffman’s essay of Capote is not an easy bit of copying mannerisms and resting on obvious twitches of a public persona. Hoffman digs deeper than normal, revealing the self-hatred in quiet moments when Capote realizes he has fallen in love with the killer while also waiting for him to die. A telling exchange occurs between him and his best friend, Harper Lee (a magnificently understated and warm Catherine Keener), where he says that there was nothing he could do to save them, and she responds with “Maybe, but the fact is that you didn’t want to.” Lee is the only character in the film who sees Capote for who he truly is, and she telegraphs it often.

Scenes of Capote gad flying about town with the rich and famous, poking fun at the rubes he’s documenting, then returning to Kansas and charming them with stories of the glitterati and movie stars display his contradictions. If one knows anything about his life, one knows that Capote’s childhood was marked by loneliness and abandonment, his public face a carefully cultivated persona to get love and attention from whoever was present. These scenes reveal that neediness and sadness. While not always a flattering portrait, Capote is fair-handed in detailing both the good and bad of a real person. What makes the film work so well, and Hoffman’s performance so perfect, is how it stares Capote’s moral and artistic disintegration straight in the eye and never flinch for a moment.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections