Numerous classic films that have been canonized more for their historical import than their long-lasting merits. One such example of this phenomenon is Planet of the Apes, one of Charlton Heston’s many jaundiced, deeply cynical science-fiction action-adventure films which try extra hard to work as deep political allegories. Apes fares better than many of those films, but it still suffers from numerous problems that leave it just missing the unimpeachable classic mark.

With numerous sequels, remakes, and a currently popular rebooted franchise in theaters, does one really need to summarize or explain the basic plot of Planet of the Apes? Scientists on a space mission in 1972 crash land on a foreign planet and learn that the year is 3978. Upright talking apes run the planet, humans are enslaved and largely mute creatures reverted down to a feral state, Heston can only look on at the madness and rage against it. The writers use this topsy-turvy world to explore issues of science versus religion, race relations, and man’s confusion over technological progression and destruction.

None of it is particularly subtle, much of it boldly stated and with clunky dialog, cardboard thin characters, and uneven pacing that has the film oscillate between intriguing setups and long passages of awkward doldrums. Far too much of the film is eaten up by these moments in which the human characters stare soulfully into the barren, harsh landscape, or give vaguely meaningful looks to each other while their ape masters coldly treat them like test subjects or decorations. This wouldn’t be a problem if any of the human characters were even remotely interesting, but none of them are. Linda Harrison is nothing but pin-up mute babe material in a fur bikini, while Heston must contort and grimace with wild abandon, demanding answers for this strange world order and its secrets.

Far better are the three main ape characters – kindly Zira (Kim Hunter), sympathetic Cornelius (Roddy McDowell), and villainous Zaius (Maurice Evans). Emoting as best they can through Justin Chambers’s makeup, the three of them make the most lasting impression in the film, the ending image notwithstanding. Chambers makeup is another aspect of the film that gives it greater weight than it might otherwise deserve. To be blunt – it doesn’t hold up as well it should. For the time, this was a big bang, a huge evolutionary leap forward in the art of special effects makeup, but seen today these designs appear clunky, barely mobile, and like they were from the same mold. Facially, despite being different species of apes, none of them appears to be radically different from each other, only when you add in costuming and the voices of the various actors do their personalities come alive.

Yet Hunter, McDowell, and Evans seem to realize that there’s a certain amount of camp to the proceedings and go from there. Evans in particular seems to have great pride and relish in the opportunity to swing wide with his characterization. Hunter was an underrated actress, watch The 7th Victim or her Oscar winning work in A Streetcar Named Desire for proof, who was blacklisted and didn’t get the film opportunities her talents deserved. Here she manages to emote the strongest through the makeup, frequently appearing to be empathetic to Heston’s plight and the most intellectually curious about him. McDowell makes a lasting impact for his peculiar vocal presence alone, combined with his moral conflict over what to do about this strange talking human.

In many instances, Planet of the Apes feels like a two hour long episode of The Twilight Zone, for good and bad. It’s a strong premise, and frequently manages to craft movie magic with its pop culture landmark moments and strong performances, but the script never feels the need to make the characters more compelling or the dialog smoother. Yet none of this matters when we get to the ending scene, a moment so infamous that I’m not even sure there are people out there who don’t know what it is, whether or not they’ve even seen the film. If an ending can make or break a movie, then Apes stuck a difficult landing and got the gold despite its faults in performance up to this moment. I still think the film is a classic, but it’s not a masterpiece.

Planet of the Apes

Posted : 10 years, 11 months ago on 29 July 2014 04:53

(A review of Planet of the Apes)

Posted : 10 years, 11 months ago on 29 July 2014 04:53

(A review of Planet of the Apes) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Our Town

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 11:04

(A review of Our Town)

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 11:04

(A review of Our Town)Thorton Wilder’s play is an indomitable classic, a work that twisted and contorted the very fabric of stage dramatics during its time. So why is the movie version so damn underwhelming? It’s never terrible, but it mostly stalls out at serviceable. Maybe because it decides on largely being a filmed document of the play rather a cinematic adaptation of it. Or maybe it’s just because certain conceits work better on stage than in film – the narrator is never fully integrated into the plot, nor is the minimalism of the production design. Think of it either way, the point is, Our Town doesn’t ever work as a film.

Our Town is a led by Martha Scott, in her film debut, and William Holden, in one of his earliest roles. Scott was inexplicably Oscar nominated for her turn here, which is never truly great nor terrible, just merely workman-like. That she bested, say, Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday for recognition is baffling. And Holden is awkward in these All-American boy-next-door parts, he soared once Billy Wilder got his hands on him. Everyone else does fine work, but I’ve seen all of them perform better in other films.

Artifice and sentimentality are the primary means of operation in Our Town. The main problem with this is simple: sentimentality in order to be effective must be earned, which Our Town never properly does. Artifice in a film, especially one from the studio era, is to be expected. Modern films don’t speak this romantic language as fluently. And Our Town’s insistence on giving the story a happy ending is baffling and confusing. The brilliance of the play was that the third act took such a sudden departure into the surreal and embraced darkness. The film only commits to this change halfway, which is a good enough summary for the film adaptation as a whole.

Our Town is a led by Martha Scott, in her film debut, and William Holden, in one of his earliest roles. Scott was inexplicably Oscar nominated for her turn here, which is never truly great nor terrible, just merely workman-like. That she bested, say, Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday for recognition is baffling. And Holden is awkward in these All-American boy-next-door parts, he soared once Billy Wilder got his hands on him. Everyone else does fine work, but I’ve seen all of them perform better in other films.

Artifice and sentimentality are the primary means of operation in Our Town. The main problem with this is simple: sentimentality in order to be effective must be earned, which Our Town never properly does. Artifice in a film, especially one from the studio era, is to be expected. Modern films don’t speak this romantic language as fluently. And Our Town’s insistence on giving the story a happy ending is baffling and confusing. The brilliance of the play was that the third act took such a sudden departure into the surreal and embraced darkness. The film only commits to this change halfway, which is a good enough summary for the film adaptation as a whole.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Svengali

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 11:04

(A review of Svengali)

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 11:04

(A review of Svengali)By most accounts, this is a psychological drama with numerous horror film trappings but Svengali never finds a comfortable setting. Loosely based on George du Maurier’s novel Trilby, this film adaptation sees John Barrymore take on the titular role of an obsessive hypnotist with his sights set on a nude model, Trilby. Barrymore is deliciously hammy in the role, and the film has a few moments of divine inspiration, but it’s mostly just amateur-hour.

To have been truly effective, Svengali needed a strong actress in the role of Trilby to sell the overarching drama. Marian Marsh is not that actress. Almost cringe inducing and precocious in the first few moments, she finally settles into a more endurable mode once the darkness creeps into the plot. But Barrymore blows her off the screen, and Marsh’s presence never provides a visible or logical reason for so many different men to be obsessed with her.

While clearly in debt to German Expressionist cinema, Svengali is mostly all look and no emotional excavation. Unlike, say, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari which utilized its topsy-turvy sets to describe the main character’s tenuous emotional state, Svengali gives its characters a pleasing set and no thoughts or emotions to play out. Only on a few occasions towards the end does the film manage to scrap together some interesting ideas. A late-night psychic call-out from Svengali to Trilby sticks in the mind. Svengali is across town, but calls out to her, and the camera pans out from his apartment clear across the rooftops before resting on the sleeping Trilby. This sequence lingers in the mind for its imagination and for displaying the obsessive nature at the heart of the story. But that is Svengali in summary: brilliant tiny moments surrounded by wooden and indifferent film-making.

To have been truly effective, Svengali needed a strong actress in the role of Trilby to sell the overarching drama. Marian Marsh is not that actress. Almost cringe inducing and precocious in the first few moments, she finally settles into a more endurable mode once the darkness creeps into the plot. But Barrymore blows her off the screen, and Marsh’s presence never provides a visible or logical reason for so many different men to be obsessed with her.

While clearly in debt to German Expressionist cinema, Svengali is mostly all look and no emotional excavation. Unlike, say, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari which utilized its topsy-turvy sets to describe the main character’s tenuous emotional state, Svengali gives its characters a pleasing set and no thoughts or emotions to play out. Only on a few occasions towards the end does the film manage to scrap together some interesting ideas. A late-night psychic call-out from Svengali to Trilby sticks in the mind. Svengali is across town, but calls out to her, and the camera pans out from his apartment clear across the rooftops before resting on the sleeping Trilby. This sequence lingers in the mind for its imagination and for displaying the obsessive nature at the heart of the story. But that is Svengali in summary: brilliant tiny moments surrounded by wooden and indifferent film-making.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Iron Mask

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 11:04

(A review of The Iron Mask)

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 11:04

(A review of The Iron Mask)What a shame that the main print available for The Iron Mask is the 1952 re-release that added an oppressive voiceover. If viewed in its original silent incarnation, I have the strongest feeling that it would be a vast improvement. But 1929 was the year of The Jazz Singer, and silent films were numbered. The Iron Mask feels like it should be the closing image of Douglas Fairbanks legendary career, and alternately like a great icon feeling uncertain about his place in the upcoming new all-talking world of cinema.

The Iron Mask is a sequel to one of Fairbanks’s great films, The Three Musketeers, and a speed-read through Alexandre Dumas’s novel The Victome of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later, most popularly known for the segment dubbed “The Man in the Iron Mask.” This film reunites many of the supporting players from the 1921 Musketeers, and their various death scenes play like goodbyes to old friends. The Iron Mask also features Fairbanks fighting to maintain his swashbuckling persona, while acknowledging that his reign as king may be over, as this film features his lone death scene in the silent era.

And it would be a fitting, if bittersweet, farewell to the original king of daring adventure cinema if not for Douglas Fairbanks Jr.’s decision to include a voiceover for his re-released version. The images play out in the heightened reality of silent film, and narrating their every move, thought and action creates a strange dissonance between what is happening onscreen and having it spoon-fed to us. The poetry and grace of silent acting and it’s dream-like logic is undercut. Yet there is Fairbanks in the center of it all, holding the film together and saying goodbye to his throne and still promising greater adventures beyond this point summarized in one of the final images of the film – the Musketeers reunited in heaven and walking into the great beyond.

The Iron Mask is a sequel to one of Fairbanks’s great films, The Three Musketeers, and a speed-read through Alexandre Dumas’s novel The Victome of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later, most popularly known for the segment dubbed “The Man in the Iron Mask.” This film reunites many of the supporting players from the 1921 Musketeers, and their various death scenes play like goodbyes to old friends. The Iron Mask also features Fairbanks fighting to maintain his swashbuckling persona, while acknowledging that his reign as king may be over, as this film features his lone death scene in the silent era.

And it would be a fitting, if bittersweet, farewell to the original king of daring adventure cinema if not for Douglas Fairbanks Jr.’s decision to include a voiceover for his re-released version. The images play out in the heightened reality of silent film, and narrating their every move, thought and action creates a strange dissonance between what is happening onscreen and having it spoon-fed to us. The poetry and grace of silent acting and it’s dream-like logic is undercut. Yet there is Fairbanks in the center of it all, holding the film together and saying goodbye to his throne and still promising greater adventures beyond this point summarized in one of the final images of the film – the Musketeers reunited in heaven and walking into the great beyond.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Harold and Maude

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 09:40

(A review of Harold and Maude)

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 09:40

(A review of Harold and Maude)You can look at me like I’m crazy all you want, but I find Harold and Maude to be an utterly charming picture of unconventional love. Granted, it’s unconventional love story is really a device used to tell us that life is worth living, and to do what makes you happy while you’re living it. How anyone could not be completely charmed by this strangely whimsical story of a young death obsessed boy and an elderly woman with a lust for life?

Director Hal Ashby and writer Colin Higgins are non-judgmental in presenting both of these individuals and exploring their relationship together. Essentially presenting a generational conflict and finding the ones in power to be suffering from a type of emotional malaise. Harold may be obsessed with death and prone to theatrical displays of this obsession, but at least he isn’t his mother so enamored and slavish to bourgeois comforts.

Our empathy lies perfectly square with Harold and Maude, a yin and yang if there ever was one. And much of the genius lies in the casting of Bud Cort and Ruth Gordon. Cort’s wide-eyed stare perfectly encapsulates the winking suicidal tendencies of Harold. Even when smiling, which is only in brief moments, Cort appears to be frowning internally, and constantly appears to be marching towards an unseen funeral. Whereas Ruth Gordon, who quietly steals the movie which is only fitting given her character is a kleptomaniac, is pure energy and sunny disposition. Here is woman who can stare life and/or death in the face, and greet it with a big smile.

The two of them meet up while crashing a funeral, and their strange friendship blossoms from there, slowing turning from a meeting of kindred spirits and polar opposites, at the same time. There human connection is the very heart of the film, underscored by Cat Stevens score. A collection of pop songs which work in much the same way as a regular orchestral score would, Stevens uses his pop songs to underline the drama, or to add some levity to an otherwise macabre world.

While the world of Harold and Maude may be a strange one, there is still a shimmering innocence and sense of hope, a longing to make a connection. This idealism is what I think makes the movie so lasting as a cult film. Here is a film which doesn’t judge its two characters, and even presents them as the happiest and most normal person in the entire thing. Harold’s mother is obsessed with him repeating the process of marriage and middle-class domesticity, and his series of dates frequently culminate him staging a new bizarre death and his mother’s indifference to his neurosis, viewing it more as a nuisance than anything else. Ashby clearly wants us to understand that this lifestyle isn’t for Harold, maybe it isn’t even for you, and that’s fine. This is a fable of love and death which tells us happiness is a personal thing, and however you chose to define it is something worth fighting for.

Director Hal Ashby and writer Colin Higgins are non-judgmental in presenting both of these individuals and exploring their relationship together. Essentially presenting a generational conflict and finding the ones in power to be suffering from a type of emotional malaise. Harold may be obsessed with death and prone to theatrical displays of this obsession, but at least he isn’t his mother so enamored and slavish to bourgeois comforts.

Our empathy lies perfectly square with Harold and Maude, a yin and yang if there ever was one. And much of the genius lies in the casting of Bud Cort and Ruth Gordon. Cort’s wide-eyed stare perfectly encapsulates the winking suicidal tendencies of Harold. Even when smiling, which is only in brief moments, Cort appears to be frowning internally, and constantly appears to be marching towards an unseen funeral. Whereas Ruth Gordon, who quietly steals the movie which is only fitting given her character is a kleptomaniac, is pure energy and sunny disposition. Here is woman who can stare life and/or death in the face, and greet it with a big smile.

The two of them meet up while crashing a funeral, and their strange friendship blossoms from there, slowing turning from a meeting of kindred spirits and polar opposites, at the same time. There human connection is the very heart of the film, underscored by Cat Stevens score. A collection of pop songs which work in much the same way as a regular orchestral score would, Stevens uses his pop songs to underline the drama, or to add some levity to an otherwise macabre world.

While the world of Harold and Maude may be a strange one, there is still a shimmering innocence and sense of hope, a longing to make a connection. This idealism is what I think makes the movie so lasting as a cult film. Here is a film which doesn’t judge its two characters, and even presents them as the happiest and most normal person in the entire thing. Harold’s mother is obsessed with him repeating the process of marriage and middle-class domesticity, and his series of dates frequently culminate him staging a new bizarre death and his mother’s indifference to his neurosis, viewing it more as a nuisance than anything else. Ashby clearly wants us to understand that this lifestyle isn’t for Harold, maybe it isn’t even for you, and that’s fine. This is a fable of love and death which tells us happiness is a personal thing, and however you chose to define it is something worth fighting for.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Bull Durham

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 09:40

(A review of Bull Durham (1988))

Posted : 11 years ago on 30 June 2014 09:40

(A review of Bull Durham (1988))Romance, sex, religion, baseball, Bull Durham argues that they’re all one and the same. This isn’t some story about a Major Leaguer or a scrappy up-start; this is a down and dirty look at those stuck in the part-time. Jamming together equal parts sports movie with romantic comedy, Bull Durham finds the great American pastime in lusty and robust health.

Bull Durham gets a lot right, so we can forgive it, even embrace it, when it starts to play out like the fantasies of the writer. The braggadocio and salty language of the locker room feels real and lived in. The fact that this movie gives the lie to the “healing powers” of the sport is wonderful, showing instead how the obsession begins to overcome all other aspects of their life. Who cares if a poetry reading incredibly sexy baseball whisper/groupie is pure invention, I say thank god for her. Annie Savoy is a great character, and probably the most interesting one of the three leads.

Kevin Costner’s wise veteran is a salt-of-the-earth type, while Tim Robbins’s cocksure upstart pitcher is pure mush-brains, buts it’s Susan Sarandon’s Walt Whitman quoting seductress that walks away with the movie. Her character could have easily dipped into a sad case study of someone unable to face the march of time, but Sarandon gives Annie a spark of life and a genuine love for all things baseball. Her one love affair a season, during which she teaches the prospective players how to be great, is of course complicated by the presence of Costner. That the film is a love triangle as much as it is a knowing love letter to baseball should clue you in to where everyone lands in the end.

Yet it’s still a satisfying journey with these three people. Sure, Robbins is pure comic gold as the dumbest and least interesting of the three, but he’s still worth spending time with as he transitions from braggart to someone of more substance, if not too much more mind. It’s only mildly ironic that Robbins and Sarandon began their decades long love affair, because she and Costner have an erotic spark that threatens to ignite the celluloid every moment that they’re in the same frame. These are great people to spend time with, ones, who have had hard knocks done to them by life, but still find great love and joy in their shared passion.

But Bull Durham is considered one of the best sports movies because of the minor key moments which ring as truth. Minor League players being dropped and promised coaching jobs as a cushion for the harsh impact feel lived in. These type of acute observations only make the film more enjoyable and warm. It’s easy to forgive, even ignore, that the movie may be running a tad too long and getting a little flabby as it rushes towards its ending, but dammit it’s hard to say goodbye to these characters and the genuine amount of love and respect the film has for its subjects.

Bull Durham gets a lot right, so we can forgive it, even embrace it, when it starts to play out like the fantasies of the writer. The braggadocio and salty language of the locker room feels real and lived in. The fact that this movie gives the lie to the “healing powers” of the sport is wonderful, showing instead how the obsession begins to overcome all other aspects of their life. Who cares if a poetry reading incredibly sexy baseball whisper/groupie is pure invention, I say thank god for her. Annie Savoy is a great character, and probably the most interesting one of the three leads.

Kevin Costner’s wise veteran is a salt-of-the-earth type, while Tim Robbins’s cocksure upstart pitcher is pure mush-brains, buts it’s Susan Sarandon’s Walt Whitman quoting seductress that walks away with the movie. Her character could have easily dipped into a sad case study of someone unable to face the march of time, but Sarandon gives Annie a spark of life and a genuine love for all things baseball. Her one love affair a season, during which she teaches the prospective players how to be great, is of course complicated by the presence of Costner. That the film is a love triangle as much as it is a knowing love letter to baseball should clue you in to where everyone lands in the end.

Yet it’s still a satisfying journey with these three people. Sure, Robbins is pure comic gold as the dumbest and least interesting of the three, but he’s still worth spending time with as he transitions from braggart to someone of more substance, if not too much more mind. It’s only mildly ironic that Robbins and Sarandon began their decades long love affair, because she and Costner have an erotic spark that threatens to ignite the celluloid every moment that they’re in the same frame. These are great people to spend time with, ones, who have had hard knocks done to them by life, but still find great love and joy in their shared passion.

But Bull Durham is considered one of the best sports movies because of the minor key moments which ring as truth. Minor League players being dropped and promised coaching jobs as a cushion for the harsh impact feel lived in. These type of acute observations only make the film more enjoyable and warm. It’s easy to forgive, even ignore, that the movie may be running a tad too long and getting a little flabby as it rushes towards its ending, but dammit it’s hard to say goodbye to these characters and the genuine amount of love and respect the film has for its subjects.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

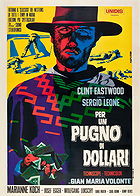

A Fistful of Dollars

Posted : 11 years ago on 27 June 2014 08:29

(A review of A Fistful of Dollars)

Posted : 11 years ago on 27 June 2014 08:29

(A review of A Fistful of Dollars)A Fistful of Dollars sees Sergio Leone first dips into the Spaghetti Western, and his first teaming with Clint Eastwood. It is to watch Leone’s later operatic, stylistic obsessions and choices to be in their embryonic form. It is to watch Eastwood’s film persona being hammered into place and his movie star charisma coming into full bloom. Sure, the plot is purely recycled from Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, which was already heavily borrowed from Dashiell Hammett’s great noir novel Red Harvest, but A Fistful of Dollars is a loose remake done right.

It may not quite hold its own weight next to sprawling masterpieces like Once Upon a Time in the West or The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, but it’s still a damn good time. The extreme close-ups, the dirt and grit in every frame, the poetic expressions of violence, the long-silence punctuated by loud gun shots, the Ennio Morricone score that haunts every moment – all of Leone’s genius is here. And if you’re interested in pure expressions of cinema, films which alternate between wide panoramas and tightly framed faces, Leone’s oddball westerns are a great deal of joy to behold.

These are Westerns beamed in from another planet, keener on providing expressionistic shots of wide landscapes and punctured by operatic displays of emotions and goofy sidekicks that pose as comic relief. Standing in the center of Leone’s great, loosely entwined trilogy is Eastwood’s “Man with No Name.” His granite face and permanent squint are visual symbolizes that what we’re dealing with is a murky area in which there are no longer clear delineations between good and bad. Eastwood is pure anti-heroism, and the stoic yet ultimately decent heroes of John Wayne and Gary Cooper’s westerns are now things of the past.

It may not quite hold its own weight next to sprawling masterpieces like Once Upon a Time in the West or The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, but it’s still a damn good time. The extreme close-ups, the dirt and grit in every frame, the poetic expressions of violence, the long-silence punctuated by loud gun shots, the Ennio Morricone score that haunts every moment – all of Leone’s genius is here. And if you’re interested in pure expressions of cinema, films which alternate between wide panoramas and tightly framed faces, Leone’s oddball westerns are a great deal of joy to behold.

These are Westerns beamed in from another planet, keener on providing expressionistic shots of wide landscapes and punctured by operatic displays of emotions and goofy sidekicks that pose as comic relief. Standing in the center of Leone’s great, loosely entwined trilogy is Eastwood’s “Man with No Name.” His granite face and permanent squint are visual symbolizes that what we’re dealing with is a murky area in which there are no longer clear delineations between good and bad. Eastwood is pure anti-heroism, and the stoic yet ultimately decent heroes of John Wayne and Gary Cooper’s westerns are now things of the past.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

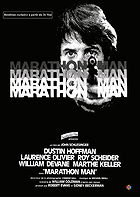

Marathon Man

Posted : 11 years ago on 27 June 2014 08:29

(A review of Marathon Man (1976))

Posted : 11 years ago on 27 June 2014 08:29

(A review of Marathon Man (1976))Marathon Man is an awkward marriage between political/espionage thriller and Nazis-on-the-loose chiller. There are moments of sublime horror and some great acting on display, but the film is ultimately undone by its instance on being more important or better than it actually is. There are large swaths of time in which the film is a bore, and more than a few moments in which the story’s various twists and turns strain credibility to the breaking point.

It tells the story of a man, Dustin Hoffman in sweaty and twitchy mode, stumbling into a conspiracy involving the US government, Nazis in America, gems, and his dead brother (Roy Scheider, who is magnetic and not in this long enough). The film gets fairly preposterous towards the middle and end as everyone Hoffman keeps meeting is somehow tied into the conspiracy. And I do mean everyone. After a while it did nothing but make me strain from trying not to roll my eyes.

That isn’t to say that Marathon Man isn’t effective in spots. Whenever Laurence Olivier appears on-screen the film comes alive, blooming into something deeper and chillier. Olivier dominates the film, having one of those characters who are referenced constantly before finally being revealed. It’s a difficult task for any actor to live up these expectations, but Olivier brings a legacy and weight as an actor which lends credence to the idea we have built up. Olivier is possibly even more terrifying once he begins performing dental surgery and spouting off “Is it safe?” repeatedly.

Olivier’s work almost makes some of the wilder and downright odd plot twists believable. Hoffman clearly strains to make sure we get all of the key changes, as his character travels from meek pacifist to gun-wielding avenger, but Olivier is pure urbane charisma turned into ominous authority and gleeful disdain for others. Director John Schlesinger can create some wonderful bits of tension, like a walk down the street in which Olivier’s former Nazi guard is recognized by his victims. Many of the players work hard to make Marathon Man into an important film, but the film is riddled with logical holes and moments that stand out for being so good next to others that are dull.

It tells the story of a man, Dustin Hoffman in sweaty and twitchy mode, stumbling into a conspiracy involving the US government, Nazis in America, gems, and his dead brother (Roy Scheider, who is magnetic and not in this long enough). The film gets fairly preposterous towards the middle and end as everyone Hoffman keeps meeting is somehow tied into the conspiracy. And I do mean everyone. After a while it did nothing but make me strain from trying not to roll my eyes.

That isn’t to say that Marathon Man isn’t effective in spots. Whenever Laurence Olivier appears on-screen the film comes alive, blooming into something deeper and chillier. Olivier dominates the film, having one of those characters who are referenced constantly before finally being revealed. It’s a difficult task for any actor to live up these expectations, but Olivier brings a legacy and weight as an actor which lends credence to the idea we have built up. Olivier is possibly even more terrifying once he begins performing dental surgery and spouting off “Is it safe?” repeatedly.

Olivier’s work almost makes some of the wilder and downright odd plot twists believable. Hoffman clearly strains to make sure we get all of the key changes, as his character travels from meek pacifist to gun-wielding avenger, but Olivier is pure urbane charisma turned into ominous authority and gleeful disdain for others. Director John Schlesinger can create some wonderful bits of tension, like a walk down the street in which Olivier’s former Nazi guard is recognized by his victims. Many of the players work hard to make Marathon Man into an important film, but the film is riddled with logical holes and moments that stand out for being so good next to others that are dull.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

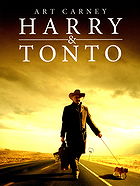

Harry and Tonto

Posted : 11 years ago on 27 June 2014 08:29

(A review of Harry and Tonto (1974))

Posted : 11 years ago on 27 June 2014 08:29

(A review of Harry and Tonto (1974))My praise and criticism of Harry and Tonto reside in the same place: Art Carney’s central performance. At once, Carney pulls this film away from generic TV Movie of the Week platitudes through sheer force of will, but it’s not a performance of transcendence. His Oscar win feels like a “Give it to the veteran” moment when compared to the career-defining work of Al Pacino in The Godfather Part II, Jack Nicholson in Chinatown, or Dustin Hoffman in Lenny, all of whom he beat out.

I didn’t really know what to expect from Harry and Tonto going in, and I was greeted with a pleasant but forgettable story about an elderly man going across country with his pet cat. As the film went along, it never felt palatable or emotionally strong enough to make a lasting impression. It was too satisfied with its own minor accomplishments, but nicely sincere in many moments. At times, the film dipped too far into generic territory, never truly establishing many of the motivations or giving its characters terribly interesting things to say or do. It makes the central character a bit of a crank, and surrounds him with colorful archetypes posing on his children and long-lost lovers. These characters only come across as ungrateful, and this doesn’t feel true. There has to be a reason that Harry’s been thrust into isolation and estrangement, but the film never bothers to explore this.

Luckily, Harry and Tonto has Art Carney trying to lead the way. He’s most engaging in the very beginning, which sees him essaying a portrait on old age’s painful emotional isolation. Once we hit the road, he begins to take a more supporting role to the cavalcade of colorful people he meets along the way. It’s commendable work, and a solid performance, yet it feels to be missing a certain spark that makes the leap between a solid performance and one that feels award-worthy. I never felt that same spark of life in this performance that I felt from Pacino in The Godfather Part II, as one example from the pool of nominees.

I didn’t really know what to expect from Harry and Tonto going in, and I was greeted with a pleasant but forgettable story about an elderly man going across country with his pet cat. As the film went along, it never felt palatable or emotionally strong enough to make a lasting impression. It was too satisfied with its own minor accomplishments, but nicely sincere in many moments. At times, the film dipped too far into generic territory, never truly establishing many of the motivations or giving its characters terribly interesting things to say or do. It makes the central character a bit of a crank, and surrounds him with colorful archetypes posing on his children and long-lost lovers. These characters only come across as ungrateful, and this doesn’t feel true. There has to be a reason that Harry’s been thrust into isolation and estrangement, but the film never bothers to explore this.

Luckily, Harry and Tonto has Art Carney trying to lead the way. He’s most engaging in the very beginning, which sees him essaying a portrait on old age’s painful emotional isolation. Once we hit the road, he begins to take a more supporting role to the cavalcade of colorful people he meets along the way. It’s commendable work, and a solid performance, yet it feels to be missing a certain spark that makes the leap between a solid performance and one that feels award-worthy. I never felt that same spark of life in this performance that I felt from Pacino in The Godfather Part II, as one example from the pool of nominees.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

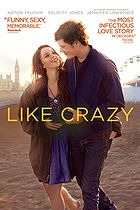

Like Crazy

Posted : 11 years ago on 16 June 2014 07:10

(A review of Like Crazy)

Posted : 11 years ago on 16 June 2014 07:10

(A review of Like Crazy)Call me heartless if you will, but by the end of Like Crazy I just wanted these two to hurry up and get over each other. Maybe it’s because I never felt their central bond to be all that strong, or maybe it had something to do with the music video style imagery of quick edits meant to symbolize passing time and sunlit beach strolls. Either way, I never got why these two just couldn’t let their relationship go.

They meet-cute in a college class, she’s a British exchange student and he’s an American studying furniture design. They’re both attractive, bright people who we hope will succeed in their futures. But their romance lasts only a short time before complications ensue to pull them apart. She overstayed her student visa and now can’t reenter the country. They try to visit and talk to each other when they can, but life keeps interrupting. Yet the script insists that they belong together, so it bends and contorts to try and make them function and work together. Their romance seems more winsome and idealistic, and since they’re kept apart for so much of the film it’s hard to see what’s wrong with new love interests played by Jennifer Lawrence and Charlie Bewley.

Like Crazy does have two solid leads in Anton Yelchin and Felicity Jones. Jones in particular is the real revelation in this film. The two of them manage to make a few segments exude some form of genuine emotion and feeling. A late night phone call which sees the two of them trying to convince each other that everything is fine, and will remain that way, is tender and pulls at the heart. But Like Crazy never bothers to give us a reason to care about this duo, and only half of it seems truly interested or invested in the romance and its outcome. A film like this requires a believable romance at the center to make us go along with it, but this one never provides it. What it does provide is a case that Jones is a great talent just waiting for a better vehicle to come along and launch her into bigger, better things. Like Crazy is handsomely made and nicely acted, but is curiously wooden.

They meet-cute in a college class, she’s a British exchange student and he’s an American studying furniture design. They’re both attractive, bright people who we hope will succeed in their futures. But their romance lasts only a short time before complications ensue to pull them apart. She overstayed her student visa and now can’t reenter the country. They try to visit and talk to each other when they can, but life keeps interrupting. Yet the script insists that they belong together, so it bends and contorts to try and make them function and work together. Their romance seems more winsome and idealistic, and since they’re kept apart for so much of the film it’s hard to see what’s wrong with new love interests played by Jennifer Lawrence and Charlie Bewley.

Like Crazy does have two solid leads in Anton Yelchin and Felicity Jones. Jones in particular is the real revelation in this film. The two of them manage to make a few segments exude some form of genuine emotion and feeling. A late night phone call which sees the two of them trying to convince each other that everything is fine, and will remain that way, is tender and pulls at the heart. But Like Crazy never bothers to give us a reason to care about this duo, and only half of it seems truly interested or invested in the romance and its outcome. A film like this requires a believable romance at the center to make us go along with it, but this one never provides it. What it does provide is a case that Jones is a great talent just waiting for a better vehicle to come along and launch her into bigger, better things. Like Crazy is handsomely made and nicely acted, but is curiously wooden.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections