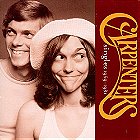

Blender dubbed them the “masters of soft rock,” and that sums it up about as neatly as possible. Karen Carpenter’s voice had a resignation, a fatigue towards romantic labors lost and a haunting quality that gave an edge to even the sappiest of songs. That haunted vocal texture made “Sing” quietly authoritative, after all.

This brother/sister duo came armed with a bevy of songwriters that would make numerous acts green with envy – Burt Bacharach, Paul Williams, Leon Russell, just to name a few – and Richard Carpenter gave them productions and arrangements that turned them slightly askew. They were toothsome, plainly attractive, very talented, and melancholic in the best of ways beneath that shiny surface.

The innate sadness of “Rainy Days and Mondays” doesn’t spring from nowhere. There was a real depth of feeling to this duo, mainly found in Karen’s velvety lower range. Her melodic sense was so unique and acute that she can find surprising details in her line readings. Try singing along with her and realize just how hard it is to copy her technique and style.

Am I arguing that the Carpenters are better than your dusty memories, or pop cultural shorthand for them as square pegs? You’re damn right I am. “Close to You” and “Hurting Each Other” would feel right at home on a Fleetwood Mac album, and everybody loves them. They endure because there’s something real going on beneath that “nice kids playing nice music” veneer, and it was tragic.

It’s too easy to tie the band’s tragic demise to this burbling darkness, but it is all of one piece of their history. Singles 1969 – 1981 places the emphasis on the earlier, better years before Karen’s health struggles and Richard’s addiction problems caused the group to lose focus (“Please Mr. Postman” and “Touch Me When We’re Dancing” are… not great), but those earlier songs are classics. “For All We Know” opens and closes the album essentially wrapping up the argument that they’ve got a better backlog of material than originally thought.

It’s a persuasive and compelling argument, especially when evidenced with “Superstar,” “Hurting Each Other,” and “We’ve Only Just Begun.” I’m particularly fond of the defeatist attitude scarred by battered hope she brings to “I Won’t Last a Day Without You.” Twenty-one songs feel just right as the smooth grooves blend into one another nicely, and there doesn’t appear to be any glaring omission.

The tragedy of their end is impossible to separate from the music nowadays but try. Karen Carpenter remains one of rock’s best singers, and she was one hell of an underrated drummer. Color me surprised that I love this collection as much as I do, but its softness appeals to me. You can try to fight it but, eventually, you just have to succumb to the inevitable fact that the Carpenters were a great band.

DOWNLOAD: “Goodbye to Love,” “Superstar,” “I Won’t Last a Day Without You”

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,