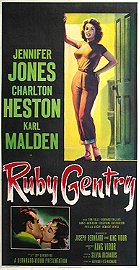

Equal parts swampland noir and southern-fried melodrama, Ruby Gentry is a pulpy mess of lurid proportions that buckles under the miscasting of the two leads. Jennifer Jones basically gives another version of the same performances she gave in Duel in the Sun and Gone to Earth, and can’t quite make her Ruby stand out enough from those two indelible creations. Charlton Heston is typically wooden, generates no chemistry with Jones, and doesn’t display any charm or magnetic sexuality that would indicate why Ruby is so erotically fixated upon him. They’re not helped by a script that is sacked with an unnecessary narration, a bevy of clichés and a pervading sense of predictability, and a failure to do more than superficial gestures towards the characters and their motivations. The only things that make Ruby Gentry tolerable are the tragic climax in the misty swamps and Karl Malden’s layered performance that gives this material more poetry than its worth.

Ruby Gentry

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 16 November 2017 04:03

(A review of Ruby Gentry)

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 16 November 2017 04:03

(A review of Ruby Gentry) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

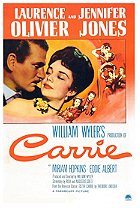

Carrie

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 15 November 2017 10:22

(A review of Carrie (1952))

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 15 November 2017 10:22

(A review of Carrie (1952))William Wyler’s adaptation of Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie is marred by the constrictions imposed by the production code, and the material is never given the fully-realized treatment it deserves. There’s also a persistent feeling that many of the major players involved weren’t giving the film their full attention. We’ve seen Wyler adapt material far better than this, and Carrie had tremendous potential to reach for greatness.

Despite being the title character, Jennifer Jones’ Carrie doesn’t experience the full-range of emotional changes and textures that Laurence Olivier’s George Hurstwood does. Carrie floats throughout the film as a good girl struggling to make good, finding herself in compromising situations, and eventually gaining success as an actress. George leaves his wife and children for Carrie, and if that pound of flesh wasn’t a big enough price, and then loses everything else before ending up as a beggar on the street. He’s the true tragedy of the film.

It doesn’t help that Olivier and Jones never generate enough chemistry with each other to make the central romance and premise believable. Olivier is very good here, but there’s a dogged feeling that he’s acting at every possible moment. He never disappears into the role completely, and that Brechtian choice makes some of the tragedy feel cold and at an arm’s-length. While he’s on a technical-level giving a greater performance than Jones, she simply “is” on the screen throughout. We believe she is this naïve girl trying to capture her American Dream at every turn, even if the film never quite gets below the surface of the characters.

Too much of Carrie feels like a weepie of doomed romance, and it has a strong sense of Madame Bovary’s misfire about it. There’s a core missing here, and it’s papered over with pretty images and some solid work from its actors (Miriam Hopkins and Eddie Albert are both terrific in limited parts). It’s a perfectly fine tearjerker, but there was the prospective for so much more.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

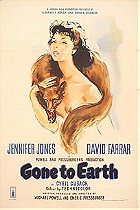

Gone to Earth

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 15 November 2017 09:42

(A review of Gone to Earth)

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 15 November 2017 09:42

(A review of Gone to Earth)I was deeply surprised to discover this little gem of a movie. It was released after the crowning achievements of The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus, and while Gone to Earth is not their equal, it is a minor glory that deserves a reappraisal and discovery. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger also give us a glimpse of what star Jennifer Jones’ career and performing styles could have been without her puppet master.

Not that David O. Selznick didn’t try to extend some oppressive control over the project, but Powell and Pressburger ignored them and made the movie they wanted to anyway. In a moment that perfectly illustrates how he harmed her career over time, Selznick eventually brought in director Rouben Mamoulian to shoot new scenes, made extensive edits, renamed it as The Wild Heart, and removed the emotional and sexual complications from the narrative. Jones’ character no longer has much agency and is an object that is reacted upon before eventually becoming a sacrificial lamb.

That version is probably more well-known to American audiences and that is a damn shame. Gone to Earth is a film just crying out for Criterion to get its hands all over it allowing for a rediscovery. It’s a film of glorious excess, in colors, in emotions, in symbolism, and in Jones’ performance, perhaps the finest of her career.

Jones won an Oscar for playing a saint, but she was always more interesting in parts that allowed her to indulge in her emotional intensity rather than repressive or girlish roles that seemed to dominated her career. It’s just more fun to watch Jones go into heat and become a wild woman in the process as her carnal urges cause chaos to everyone within her orbit. Gone to Earth allows her to blossom as it fully dives into these traits, and Jones betters her sexual live-wire in Duel in the Sun here.

Gone to Earth tells the story of Hazel (Jones), a woman in constant commune with nature and her pet fox, and the love triangle she finds herself in between a buttoned-up parson (Cyril Cusack) and a horny lord (David Farrar). Hazel’s pet fox, Foxy, becomes an extension of her own life and ultimate fate, and the opening chase from unseen hounds is a tip that what we’re about to watch is a tragedy in motion. The Archers play the whole thing as a fable of the conflicts in paganism and Christianity, in nature and civilization, and how heaven and hell are well within reach on the mortal coil if you know where to look.

Jones’ Hazel doesn’t just know where to look, but finds herself frequently wedged between the two and warring within her emotional intelligence and unbridled sexual needs. It’s all right there in the opening scene, a tremendous sequence that ranks high in the Archers filmography, as the confluence of sound design, sumptuous color, and Jones’ performance make it all at once a horrifying nightmare and a symphonic piece of fairy tale-like artwork come to life. This sequence is repeated at the very end with a completely different outcome as the hounds chasing both Hazel and Foxy come to represent so much, the complexities of love, desire, sex, religion, and propriety descending on these two to snuff out their bright lights and freedoms.

I believe it’s the mystical and fable-like overtones that keep Gone to Earth from tripping up on its own tortured melodrama, and it’s a reminder of just how wonderful the Archers are at tackling this material. Hazel frequently refers to a book left behind by her mother, and her fateful choices are never completed without the book’s presence as if she were looking for spiritual guidance from the trees and hills of the Welsh landscape and not in the confines of patriarchal religion that tries to confine her. Within Jones’ performance we believe that this woman can hear and speak with the wind, with the faerie folk and superstitions lingering around in her imagination.

Gone to Earth bombed at the box office during its time, and its failure would mark the beginning of the end for not only the Archers, but for Jones’ glory days as a leading lady. This is not shocking as even by the standards of a creative duo that made an ouroboros film out of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, and set Chaucer’s infamous tales in WWII, Gone to Earth is a deeply strange, compelling, and beautiful film. It’s as hard to pin-down as the barefoot heroine running through the hills, and we’re as enthralled by the men in her life by her and her journey as they are.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Madame Bovary

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 15 November 2017 08:21

(A review of Madame Bovary (1949))

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 15 November 2017 08:21

(A review of Madame Bovary (1949))On a surface level there’s not particular wrong with Madame Bovary, but there’s a persistent feeling that something is missing from it. Or that it’s several small somethings that are missing or slightly off which distorts the final product into something that’s decent enough. But decent enough isn’t good enough for a film with this pedigree.

Chief among the problems is a wraparound segment that finds author Gustave Flaubert (James Mason, bringing gravitas to a cameo) on trial for obscenity. It looks and feels like a mandated exercise to the production code, and Madame Bovary’s problems begin to compound from there. It’s nearly impossible to tell the story of Bovary with one hand tied behind your back, which is what it looks like here as glossy MGM standards must be met and the thematic material can only go so far.

It’s gorgeous to look at, as any film from Vincente Minnelli is at least worth a watch for the beautiful images alone, but beautiful images are not the same as emotions. This is Madame Bovary at its most muted, and the main character becomes one we quickly stop caring about and there’s still nearly 90 more minutes to spend with her before the end. It is here where the decision to present the film as a presentation of Flaubert’s oration becomes such a crisis. Emma Bovary’s actions are hard to care about or invest in when they feel removed from a believable world for us to get lost in.

There’s also the curious case of Jennifer Jones’ central performance. Jones was an actress of tremendous raw potential that some directors could harness and finesse into gloriously pyrotechnic work (Gone to Earth), or touchingly vulnerable and emotionally open (Portrait of Jennie), or a shockingly gifted comedienne (Cluny Brown), or deliciously, dangerous kitsch and carnal (Duel in the Sun). There’s numerous gaps in the script and Jones never fills them in with personality or strong choices. She merely plays the scenes as they are with no true artistry that great actors bring to their parts.

Minnelli only gets two great scenes from Jones and the rest is merely treading water. One of them is the justifiably famous ballroom waltz scene. It is a tour-de-force from every angle, but Jones’ transition from head-spinning romanticism to cold and calculating as she glimpses herself in the mirror is a knockout. It’s a shame that right after this Jones goes back to merely being serviceable in the role until a late scene where she tries to relive that glorious night by dancing alone in her hotel room. She’s delirious and lost in a dream before catching a glimpse of herself in a cracked mirror and the illusion is shattered. These two moments alone are worth investing in the time and energy to get through the rest.

No scene probably better summarizes Jones’ on-screen performances and off-screen drama than a drunk Van Heflin ruining her triumphant moment at the waltz. Replace the upper society of France with Hollywood’s mover and shakers, Heflin with David O. Selznick, and try to tell me that whole moment doesn’t work as an unintended bit of self-reflection. The man means well, but he still manages to ruin the triumph of Jones. This bit of autobiography from the star only enriches an already exceptional sequence.

It’s not that Minnelli was incapable of directing a great melodrama, look no further than his passionate work in Lust for Life, Some Came Running, and The Bad and the Beautiful, but he seems like he’s treading water here. Some sequences are alive, many are counting time until the next big sequence, and the entire thing feels curiously hollow. It’s worth watching for the waltz scene, for supporting work from Louis Jourdan, Gladys Cooper, Mason, and a few scenes of Van Heflin, and for the gorgeous production design and costumes, but it could have been so much more.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

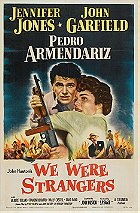

We Were Strangers

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 13 November 2017 04:07

(A review of We Were Strangers)

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 13 November 2017 04:07

(A review of We Were Strangers)A confused movie that alternately wants to be about politics in Cuba, insurgents threatening to topple an oppressive regime, and a love story, We Were Strangers is a muddy viewing experience. There’s plenty of talent lined up, but writer/director John Huston was clearly distracted while making this one. His inability to focus shows throughout, most egregiously in the faux-happy ending to a story that feels spiraling towards tragedy at the best of times, and at the worst just feels dishonest and lazy as though he treated thorny subject matter as inoffensively as possible.

So that leaves the politics only half-formed here, but what about the love story that consistently threatens to takeover? It’s a non-starter. Stars John Garfield and Jennifer Jones have an anti-chemistry that makes any of their love scenes fizzle on contact. Garfield is fine if unremarkable here, and I wonder what Huston could have done with Garfield in a juicier role.

Jones is…fine, I guess? She’s sacked with a Cuban accent that comes and goes, sometimes within the same scene, and she generally appears mildly embarrassed about appearing in this thing. The only actors turning in uniformly solid work are Gilbert Roland and Roman Novarro in supporting roles, and they’re sacrificed towards the end in favor of more close-ups of Jones’ face as her mouth does that overly active, quivering thing that seems independent from the rest of her body.

It doesn’t help that We Were Strangers was released in-between towering artistic achievements like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The Asphalt Jungle. It only makes the anemic quality of this film, despite some impressionistic and moody lighting that’s quite nice in some scenes, all the more prominent. Oh, and Ernest Hemingway was right when he told Huston how he thought he should end it. Shame he didn’t listen to him.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Portrait of Jennie

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 13 November 2017 03:53

(A review of Portrait of Jennie)

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 13 November 2017 03:53

(A review of Portrait of Jennie)After his back-to-back Best Picture victories, super-producer David O. Selznick spent the remainder of his career chasing after those two lightning in a bottle films. Several of them garnered box office results, critical acclaim, and went on to vaulted status in cinema history, and several of them imploded under their own weight. Then there’s the strange case of Portrait of Jennie, a film that spent an inordinate amount of time in post-production but emerges from its production hell woes as a stone-cold classic that’s still somehow undervalued and under-seen.

Portrait of Jennie manages to forgo the bruising running times, the needlessly meandering plot threads, and zeroes in on specific, tactile emotional senses and narrative threads and plays with them in a charming romantic fantasy. Jennie tells the story of a struggling artist (Joseph Cotten), who meets a strange little girl (Jones) that ends up both growing up incredibly fast, being his artistic muse, and providing something of a central mystery and romantic figure for the plot to orbit around. It’s a stunner that bombed in its era, but time has been incredibly kind and supportive to its abundant charms.

Much of its charm can be pinpointed to Jennie’s complete refusal to tie itself to reality or a corporeal world. Jennie is a manic pixie dead girl, and the film never tries to explain away her ghostly appearances nor judges Cotten’s artist for being the only person who can see and interact with her. As Ethel Barrymore’s supportive art dealer argues, it doesn’t matter whether we believe that he’s really seeing and interacting with Jennie, he believes it and that’s all that matters.

Barrymore lays out Cotten’s artistic problems early on in the film; he’s all impressive technical skill with no depth of feeling in his work. There’s no “love” as she puts it, and he desperately needs a little bit of it to bump him over the edge. Whether by mere coincidence or perhaps a subconscious manifestation of his desire to reach greatness, Cotten eventually meets Jones in Central Park, and this relationship will provide the missing “oomph” in his work.

Jones’ Jennie is first introduced as a young girl who makes oblique references to things long past and things yet to come in the future, including a request that Cotten wait for her to grow up. Each time she reappears, again whether by luck or conjuring, she’s gotten older, but no less ephemeral or strange in her musings and haunted memories. What’s deeply refreshing about her spirit is how quickly it is accepted as fact and we don’t spend unnecessary amounts of time waiting for Cotten to come around to the reality that his reality is touched by the supernatural.

The strength of Jones’ performance is how effortless she makes a nearly unplayable character appear. She’s bright and breathless as a little girl and a certain spark of that is kept throughout the performance even Jones essays her maturation. When she’s gone from the film, the haunted qualities already endemic to the work are enriched as she’s so compulsively watchable when she appears. Jones has a quality that was unknowable as an actress, a ability to disappear into her roles and leave us wondering who the real person was beneath the actress, and that quality finds a perfect harmony with this fey spirit.

Even better is Cotten as he’s tasked with playing a romantic lead and not an oily villain, and he’s marvelous here. We must believe that he truly finds a romantic spark with this ghost; he nails that, and that he’s also found creative inspiration in her, he nails this too. Out of the four pairings of Cotten/Jones, Portrait of Jennie is probably the best of the four (although, Duel in the Sun is a personal favorite). This would prove to be the last of their films together, and what an elegiac way to wrap up their pairing.

William Dieterle makes this man’s artistic and spiritual crisis look as haunted and dreamy as he did Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He balances a lot of tones and moments so lacking in subtlety they threaten to burst the dreamy atmosphere entirely (Lillian Gish’s nun all but giving Cotten a narrative road map with a gigantic X on it springs to mind), but its strengths overpower its weaknesses. The terror and majesty of love, obsession, and the creative process have rarely been as engrossing and tender as they are in Portrait of Jennie.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Cluny Brown

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 10 November 2017 09:31

(A review of Cluny Brown (1946))

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 10 November 2017 09:31

(A review of Cluny Brown (1946))Ernst Lubitsch and his zesty, twisty brand of comedy and wit is on display in Cluny Brown, his final completed work right before his death in 1946. (That Lady in Ermine was completed by Otto Preminger in 1948.) Cluny Brown contains many of his grand hallmarks, but it’s ever-so-slightly a notch below his grandest statements like Ninotchka and To Be or Not to Be. Class manners and snobbery is taken through the proverbial set of punches here as only Lubitsch can, and he goes out with a tart, sweet romantic bang.

Set in 1938, Cluny Brown focuses in on a Czech refugee (Charles Boyer) fleeing from the rise of Nazism, winding up staying in the manner home of an idealistic, green student (Peter Lawford), and falling for a loopy tomboy who works as a chambermaid (Jennifer Jones). It’s a zippy, light 100 minutes as Boyer and Jones elegantly dance around their inevitable romance while a lot soft, yet still spiky, satire swirls around them and some howling and sharp bits of dialog get dropped throughout. I’m deeply fond of Boyer’s description of a character’s ability to toss a cookie like a brick. Or a roundabout bit of dialog between several characters that questions why cocktail parties are a thing, and the answer becoming something of a perfect circle of skewed logic.

That “Lubitsch touch” is a potent filmic language that passed away right along with him, and it’s addictive and narcotizing in the joy it places in self-amusement and social satire. One of the funniest reoccurring jokes involve Una O’Connor as the unimpressed mother of Richard Haydn’s pharmacist. She speaks no dialog and uses a series of throat-clearing and coughs as a form of mood signaling, and this hectoring gag is a continual sort of bemusement and may be the one of the thorniest barbs Lubitsch throws out. Richard Haydn’s character certainly gets plenty of contempt thrown his way, as another running gag involves Boyer’s harassment of his shop.

Yet the English bourgeoisie don’t get off the hook here, and Lubitsch frequently underscores the happy obliviousness in which they go about their lives and the run-up to the war is merely a lot of background chatter. Lawford’s character makes a lot of capitulations towards good liberal politics, but all of it boils down to taking the right posture as its own form of back patting. And his parents, especially Reginald Owen’s clueless Sir Henry Carmel, get the sharpest bits of class-based humor. Owen is frequently at a loss for how to pronounce the last name of Boyer’s character, and wishes that his son’s loud liberal politics would quiet themselves down already. It’s a grand joy to watch Boyer’s cosmopolitan refugee play these characters against each other while he sneaks out his own agenda.

Then there’s Cluny Brown herself drifting through it, and this has to emerge as one of the greatest performances of Jennifer Jones’ career. It isn’t that she’s impossible to pin-down into socially acceptable roles and norms, no matter how much many of the characters try to do so, but the clear freedom Jones is feeling in the role. In prior films she possessed a startling intensity that threatened to topple everything out of its delicate balance, but a screwball heroine is a perfect outlet for that kind of energy. Jones feels like a natural in Lubitsch’s world and work, and she delivers both her physical comedy, moments of drama, and double-entendres with consummate skill and grace.

There’s one moment that has to be a hallmark for Jones’ career up to this point, and maybe even for her career in total, and that’s her introductory scene to the Carmel estate where she will be working as a chambermaid. She’s mistaken for a visitor of equal class as the Carmels and treated to all the luxury and kindness that affords, and once they realize the truth of the matter the oxygen in the room slowly goes out. The Carmels pull away from Cluny, but Jones sits proudly still even if momentarily defeated. All she does is look sad and hold a teacup, but Jones’ body language and inner light radiate so much more of the story.

Just as good is an earlier scene where she first meets Boyer’s character in an apartment. Cluny is the niece of a plumber and has a liking for the trade, so she appears in her uncle’s place after a service call is made. Reginald Gardiner is the fussy occupant of the apartment, and he’s applaud by her gusto with a masculine task, while Boyer is immediately intrigued and beguiled by this oddball. The three of them end of getting drunk and Jones is an absolute delight in this scene. She feels free and lacking in the self-conscious artifice that had its first twinges in moments of Since You Went Away and Love Letters. Her unguarded joy here is palpable, and Lubitsch’s camera loving watches her sway, slur, and ability to conform to social graces.

The romance at the heart of Cluny Brown is not one built on immediate sexual sparks like James Stewart and Margaret Sullivan in The Shop Around the Corner, or a clash of personalities found between Greta Garbo and Melvyn Douglas in Ninotchka. Instead, Boyer and Jones have a sweeter spark that makes your root for them nonetheless. They’re twin displaced souls, one a literal refugee while the other has a distinct inability to pick up on social cues or mores, and they recognize a certain kindred spirit in each other. You want them to have a happy life laughing at the absurdities of life together.

This is a smaller scale film, and it can’t help but feel a bit deflated in comparison to Lubitsch’s entire oeuvre, but at least it’s also the sight of a cinematic master delivering one final solid work. It’s pleasurable and absurd, frequently it’s so damn pleasurable because it’s so absurd, and Cluny Brown is probably something of an underappreciated gem.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Love Letters

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 9 November 2017 05:03

(A review of Love Letters (1945))

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 9 November 2017 05:03

(A review of Love Letters (1945))There was an abundance of these type of melodramas through the wartime years, and their peculiar rhythms and heightened sense of romance is a language that requires a dexterous tongue. Your mileage may vary, but if you can hop on Love Letters’ preposterous wavelength then its near narcotic sense of romance is potently addictive. I can't say that Love Letters is a good movie, but it’s an intoxicatingly strange one.

In a spin on Cyrano de Bergerac, adapted from a Christopher Massie novel by Ayn Rand (of all people!), finds Joseph Cotten writing love letters on behalf of his Army buddy to his sweetheart, Victoria. Cotten finds himself falling in love with Victoria, more as an ideal than as a corporeal entity, and worries that she’ll be inevitably disappointed by the reality of his Army buddy once they return home. Flash-forward a year and Cotten returns to England to discover his Army buddy and Victoria have died under mysterious circumstances, and meets an amnesic young woman (Jennifer Jones) who holds the key to this murder mystery.

It is here that Jones begins to transform into cinema’s unknowable dream girl, and she plays her part with a disquieting intensity. The material is nearly ludicrous, but Cotten and Jones manage to find a truth to it and make it work. Perhaps it’s that Cotten was best in parts that caused him to become obsessive, think of The Third Man, and Jones possessed a quality that was inherently fey. Love Letters frequently threatens to deflate into twaddle, yet Cotten and Jones go a long way towards making it hypnotic.

I’m not entirely sure if Jones deserved her Oscar nomination for her work here, but she’s quite good in the tragic flashback that unlocks the twisted knot at the center of the story. Throughout too much of the film she displays a mouth that seems to be working independently to the rest of her facial muscles, a peculiar acting choice or uncontrollable tic that she would carry throughout the rest of her career.

Praise must also go to director Wilhelm Dieterle, a man who knew how to adopt and sustain an aura of romance and tragedy no matter how perpendicular to reality that material was. This contribution cannot be stressed enough as Dieterle’s guiding hand keeps a strange brew of amnesia, secrets, romance, murder mystery, and excessively moody lighting bubbling without boiling over. I think his choice to frame it all as a gothic romance was a smart one, as that heightened tone of artifice matches the material quite beautifully.

Love Letters is preposterous nonsense, but it’s the type of studio film from its era that is charming for its refusal to remain tethered to reality. The type of film that no longer gets made, and with good reason as it seems like only this particular era in time could produce something as gloriously bonkers as this.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Since You Went Away

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 8 November 2017 04:34

(A review of Since You Went Away (1944))

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 8 November 2017 04:34

(A review of Since You Went Away (1944))After winning back-to-back Best Picture Oscars with Gone with the Wind and Rebecca, super-producer David O. Selznick returned with this three-hour long Homefront drama. Since You Went Away was Selznick’s contribution to morale boosting cinema, and a clear swipe at making an American version of Mrs. Miniver. It is overly long, heavily sentimental to its detriment, and stretched past the breaking point, but there’s still charms to be found here.

The main selling point of this movie is a handful of strong performances, but none of them quite as grounded, intelligent, and honest as Claudette Colbert in the central role. Since there’s so much material thrown into this thing, Colbert gets a chance to play a large variety of moods and scenes and she does all of them with grace. The final scene’s mawkish, nearly violent insistence on tear-wringing is practically earned by the way she shakes with emotional excitement and relief, and it plays in glorious harmony with a scene just a few moments earlier of her quietly, somberly opening a Christmas gift from her deployed husband. This would prove Colbert’s final Oscar nomination, coming ten years after her win in the fizzy, sophisticated It Happened One Night, and it was a well-earned and deserved nod for her.

While the likes of Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead, and Hattie McDaniel get sacked with their common character types, respectively likable rogue, catty socialite, and sassy maid, the likes of Monty Woolley, Robert Walker, and Jennifer Jones turn in more unique supporting work. Woolley comes on like a gruff elder, but there’s a few late moments with his grandson that reveal depths to his character that the film refuses to allow him to fully explore. Instead, Woolley deserved that Oscar nomination alone for keeping his dignity by being sacked with scene after scene of awkward comedy between him and the family dog, a bulldog named Soda.

Walker and Jones are a more unique case of the personal bleeding into the fictional. In real life they were drifting apart as Jones was beginning her affair with Selznick, the man who would become her Svengali, and on the cusp of divorcing. Jones completely buries this personal drama in her performance and romantic scenes, whereas Walker very much does not. Jones films younger but plays her girlishness too big and broad in the early moments before settling in during the meatier scenes, and Walker both looks and sounds too old for his role due to a severe problem with alcohol. Their romantic scenes are palpably tense and awkward, and a scene with a young (and incredibly beautiful) Guy Madison throbs with interpersonal drama. Madison and Walker get into a passive-aggressive argument and it’s easy to read Walker project his anguish and anger towards Selznick onto Madison in this moment while Jones wails in the background for peace.

Even better, for both parties, is their farewell scene at the train station. Jones finally stops keeping the personal demons at bay and embraces them during this scene. There’s an intensity to their goodbyes that goes beyond the confines of the characters and this scene, and the sight of Jones desperately trying to keep up with the train and screaming out “I love you darling” is alternately discomforting and touching. This feels like the emotional apex of the film, but then Since You Went Away just keeps going on.

The major problem and success of Since You Went Away is all Selznick. He assembles a strong ensemble of actors, deploys a series of smart narrative ideas, and then doesn’t know when enough is enough. This is not a movie that needed an overture, intermission, and entrance music, but there it is eating away at the running time. Not only that, but Selznick never knows when to stop adding and the last minute addition of Colbert befriending a Polish-Jewish immigrant is a needless diversion in a film filled with them. There’s Selznick persistent inability to stick to a tone, and in-between the plainspoken drama are diverging moments of broad comedy or maudlin weeping. Since You Went Away wants to pack in all of the emotions just for the sake of it, and suffers from Selznick’s demands that things be epic without a reason behind them.

There’s too many lovely details and small moments, the performance of Colbert is too strong, and there’s a splendid romanticism that lingers in its best moments to completely write off the film. Yet it’s equaled by a distinct lack of personality, a demand to be taken as something vital and important even when it’s emotionally inert and punishingly long. Since You Went Away is proof-positive that transparent Oscar bait is nearly as old as the institution itself, and just as complicated a piece of art/commerce as that albatross moniker implies.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

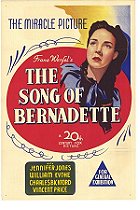

The Song of Bernadette

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 7 November 2017 09:29

(A review of The Song of Bernadette)

Posted : 7 years, 7 months ago on 7 November 2017 09:29

(A review of The Song of Bernadette)On the one hand, The Song of Bernadette is far too long and meandering for its own good, one the other hand, it’s one of the few films that tackle faith and devout belief with kindness and solemn respect. Perhaps it’s a bit too solemn though, as Bernadette can feel an awfully lot like a proselytized screed. Even worse is a persistent thrum of the film working as blatant and open Oscar bait, as if it were daring the Academy to not reward it for the sentimental treatment of its story.

What saves The Song of Bernadette from folding under its own weight is the strength of Jennifer Jones’ leading performance. This is an interior performance built from the inside out, and it would be easy to exclaim mystification over her Oscar win for such a quiet performance. Yet for all of her guilelessness and gentle-nature, there’s a core to Jones’ Bernadette that is tough. She’s also consistently girlish and ordinary, and it’s quite lovely how Jones refuses to embalm Bernadette before her time. It’s easy to admire these exterior choices, but she knocked me out in a handful of moments that would have played much differently in another actress’ hands.

First, there’s a moment where Bernadette learns that a village boy has always loved her, but has chosen to not pursue a relationship with her after watching her become an exalted religious figure. Jones merely smiles sadly, looks down, and hands him a flower while saying goodbye. She continues her quiet, smaller choices, but it’s the action going on behind her eyes that capture you. For one brief moment Jones allows her Bernadette to imagine an entire happy married life with this boy while simultaneously watching it immediately dissolve in front of her.

Another great moment is Bernadette’s death scene. It’s not hard to picture another actress going big and raging against the dying light, but Jones merely whispers and asks for prayers with such an emotional conviction and piety that it’s a little unnerving just how unshakable this girl is in her faith. Jones is playing this for real as the film cues up swelling strings and a heavenly choir. This may have been intended as an underlining to what the star was doing, but it creates a dissonance between Jones’ quaking vulnerability and acceptance of death and the melisma and histrionics of the score. Frankly, I knew about fifteen minutes into this that I probably would have voted for her too if I was an Academy member in 1943, and Jones’ refusal to play into the melodramatics of the big moments clinched it for me.

Jones’ plain, ethereal beauty makes it nearly impossible to imagine 20th Century Fox contract players like Anne Baxter, Gene Tierney, or Linda Darnell in the role. Darnell does wind up in Bernadette playing, of all things, the Virgin Mary that comes to Bernadette throughout. On paper this should mark Bernadette as an unintentional camp classic since Darnell’s bad girl screen imagine (and pregnancy) would undermine the role, but there’s no camp to be found here. Even more extraordinary, perennial good girl Loretta Young wanted the part, and didn’t get it. But it just underscores the earnestness on display if a sight like that can be played straight and accepted as such by the audience.

So thank the maker for Vincent Price’s nonbeliever and Gladys Cooper’s vicious, jealous nun in supporting roles. A quick glimpse at the 12 Oscar nominations this thing gathered included understandable nods for Anne Revere as Bernadette’s earthy, conflicted mother, and less so for Charles Bickford’s spiky, nervous Father Peyramale. Bickford is fine, but the character’s transfer from polite but hostile clergyman to supportive witness is too fast, and part of the problem with Seaton’s script is in how it frequently mishandles or slips up numerous narrative beats. But there’s a consistency in Price and Cooper’s characters and a natural progression within them that is strongly felt both in the writing and the performance.

This has to be one of Vincent Price’s best roles, and he’s the one that I wish had gotten the nomination here. He’s a man who views faith as superstition, Bernadette’s visions as mere hallucinations, and the fervor around it all as hysteria. He never plays a single moment with malice, and he gets a few shots at injecting droll humor into the proceeding somberness of the film. This all comes to a head in his climatic scene of shaken faith and mortality. He knows he’s dying of cancer, and he goes down to the grotto where he quietly says allowed for Bernadette to pray for and forgive him. There’s a tremendous amount of contradictory emotion and feeling here, much of it startlingly mature and ambiguous for such a white elephant production.

While Gladys Cooper’s vicious nun is revealed to be a woman who is jealous of this young peasant girl’s religious visions and eventual martyrdom. Cooper has a one-two punch of a venom-filled monologue followed by a dry-heave of repentance that just reminds us of how great and seamless a character actress she was. She manages to project so much using only her voice and eyes in her searing monologue against Bernadette, and then contort us to understanding where it all comes from as she prays for forgiveness. That forgiveness scene is really something as her back to us the entire time so all we have go on is the tremble in her voice and loaded pauses and stop/start rhythms.

It is in performance that the greatest joys of The Song of Bernadette can be found, as the surrounding film is good, but not great. It never quite succumbs to the goopy, eye-rolling sentimentality of the likes of The Bells of St. Mary’s, but it never wrestles with faith in as complicated and expansive a way as something like The Last Temptation of Christ. But the center cannot hold for nearly three hours, and the film wanders too far at times to retain your attention. Still, there’s a graceful, intelligent film about faith somewhere in here that’s worth a look, and you’ll get to watch Jones, Price, and Cooper deliver three performances that rank high in each of their careers.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections