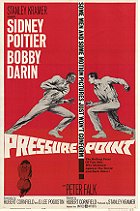

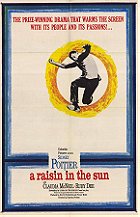

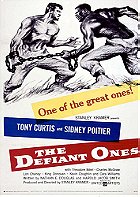

Sidney Poitier’s transformation from individual performer to all-encompassing symbol of an entire race as the lone black star of prominence is evident by the mid-60s. His thankless role of therapist to an alt-right Bobby Darin in Pressure Point was a red flag of this happening, as was his great work as a “respectable” character in Lilies of the Field. The sexuality, reservoirs of fire, and loose physicality in films like A Raisin in the Sun and The Defiant Ones is slowly giving way to transitioning him to a living marble statue.

Into this change comes 1965’s A Patch of Blue in which he engages with a supremely chaste romance with a blind girl (Elizabeth Hartman) in a narrative that broadly sweeps his black skin and her blank eyes as the same type of socially ostracizing thing. Circling around them are Shelley Winters, flirting with the full camp virago that would bloom in later films, as a truly monstrous mother and Wallace Ford as an emotionally abusive alcoholic grandpa. The film threatens to go full-on maudlin, safely “important” at any given moment with the heroes clearly wearing white hats and the villains in black ones.

What saves it is the joy in watching a group of actors this good elevate emotionally manipulative material into something nearly poetic. Hartman, in particular, is the heartbreaking glue that holds it all together as she navigates the Dickensian squalor and cruelty of her home life and the great awakening that Poitier’s kindness brings to her life. She creates a believable reality with Winters and Ford, who clearly realize they’ve gotten the showiest roles in the thing and go beyond broke and scenery chewing into almost high-art. Hell, she almost makes us believe in the possibilities of a romantic relationship between her and Poitier during an era when miscegenation was still a hot button topic.

A Patch of Blue is really her story with Poitier not quite functioning as a magical negro, but he’s still playing the part of the person who proverbially opens her eyes. His interior life and reasons for extending so much to this girl remain occasionally oblique, but he still engineers an ending that is probably the smartest and least sentimental possible. But even Poitier realized there was a problem stating, “either there were no women, or there was a woman but she was blind, or the relationship was of a nature that satisfied the taboos. I was at my wits end when I finished A Patch of Blue.”

That frustration and the real-time entombing him as an integrationist model of near sexless and peaceable interaction was going strong and wouldn’t entirely get shaken up until In the Heat of the Night’s slap heard ‘round the world. There are tiny peekaboo moments when the more mature and developed interracial love story emerges, but it often subsumed with the melodramatics of Winters’ harridan. A Patch of Blue entertains but it comes with an asterisk.

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,