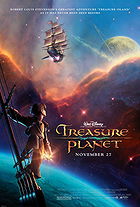

After playing around with a few films that echoed classic children’s literature, Disney throws all of its muscle behind an actual animated adaptation of a beloved piece of children’s literature. The results are not quite as enjoyable as the original stories which knew what fun parts to steal and mix in, but it’s not all the bad. I suppose the only thing that really came to mind while watching Treasure Planet was that it was just good enough, and never really objectionable.

The character designs, various alien species, new worlds, and space-age upgrades to typical pirate lore are all well done. As the film begins, something new and imaginative is introduced – a space port built like a crescent moon, a peg-leg pirate becomes a cyborg, a feline captain and her sentient rock first mate, these are just a few of the wondrous new sights to find. Would Treasure Planet work better as a silent film, I wonder? Looking at it is one thing, having to listen to it is another.

Most of the voice cast does well with the roles they are given, except for our lead, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, an actor I normally enjoy. I don’t think it’s entirely his fault, as his character is stuck on petulant brat for 75% of the film’s running time, only becoming tolerable during the loud, explosion-filled grand finale. This problem of characterization plagues the film. There’s only one instance of it being done well, and several more of it being half-done then abandoned.

Emma Thompson’s Captain Amelia emerges as a daring, tough, strong character, before she’s sidelined during the third act, and forced into an improbable love story that comes out of nowhere. Martin Short’s B.E.N., an abandoned robot taking over for Ben Gunn in the novel, grinds the film to a halt every time he appears. Ever since Robin Williams was let loose on Aladdin, various films in the Disney canon have thrown in rapid-fire comedians to bring anarchic secondary characters to life. What worked once to great charm has rarely worked so well a second, third, or fourth time.

The only character that really works is John Silver. I suppose in adapting Treasure Island making sure your variation of Long John Silver is a solid construction is not a bad idea, but it would be nice if he was operating against some well-rounded and engaging characters. The rest of them have all the personality of a 2D drawing, which they are technically speaking, while he gets a huge array of emotions and narrative twists and turns to play out. He transforms from cutthroat pirate to softer father figure over the course of the film, and he emerges as one of Disney’s more interesting, ambiguous and challenging characters in quite some time.

For a brief period of time in the early 2000s, hand-drawn animation was subject to 3D backgrounds in which the two styles never successfully merged together. I wonder what Treasure Planet would look like if the hand-drawn characters were painted with the same stylus as the backgrounds? Space whales in an early scene give an indication of how beautiful it could potentially look. Much like Titan A.E. and parts of Atlantis: The Lost Empire, the two styles never integrate well enough, and the characters occasionally look like flat cutouts on a model.

Treasure Planet is the embodiment of the phrase “all dressed up with nowhere to go.” If a film was measured entirely on how pretty its images are, this would leap to the top of the class. But somewhere along the way, they decided to skip out on developing the majority of the characters, added in three cutesy sidekicks, terrible songs by Johnny Rzeznik, and called it even. There’s some great stuff in Treasure Planet, but I can’t seem to muster up much enthusiasm for it.

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections

0 comments,

0 comments,