A return to the more full and lush animation after the wartime years found the studio releasing a series of package films held together with thin narrative constructs, Cinderella kicked off the Silver Era of Disney animation. This film is the distillation of what that era would entail: films with pieces of glorious animation, but a general sense of unsatisfactory wholes. Too many cooks in the kitchen would spoil quite a few of the films in this era, with Cinderella being a prime example.

Ostensibly, this film tells the well-known story of Cinderella, and the mechanics are all in place, yet the film adds more to center of the story, often sidelining Cinderella and her prince in favor of slapstick with cutesy mice and a cruel cat. Lucifer, Lady Tremaine’s pet, may have even more screen time than the Lady herself, who is technically the actual villain of the piece.

The basics are all there, no doubt. The backstory of tragedy befalling a young girl, her callous stepmother and wicked stepsisters, her animal helpers, the divine intervention to get her to the ball, the glass slipper, the frantic search throughout the kingdom for the maiden with the dainty foot, all present and accounted for. We speed through these set pieces, and this is a frequent problem. These are the best animated segments in the movie, but it prefers to spend more time watching cartoon mice engage in humorous side-plots.

Walt Disney rightly considering Cinderella’s transformation scene to be one of the highlights of the studio’s animation, and it is a beautiful moment. The amount of wonder and awe the animators were able to capture is a tiny piece of magic that only great animation can provide. The fairy godmother, for all of her omnipresence in the marketing of this movie, is only in one scene, but she’s the best part. Her magical spells transforming ordinary objects and animals into a coach and coachmen is the type of whimsical character specific detail that made films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs or Dumbo so memorable.

But long gone are the more detailed and stylish techniques of the Golden Era. The Silver Era has its own landmark moments, but the animation style has been flattened, partially out of necessity, partially out of economy. Aside from the fairy godmother’s sequence there are a few others in which the leads get to show some semblance of personality. Cinderella’s awakening to a new day sees her chastising the ringing bells, and proclaiming that no one will be able to take away her dreams. This leads us into a song, which is nothing but platitudes, and should be a revealing moment for her character, but abandons that notion before it even begins. What are the dreams that her heart is making? What are the dreams that the dawning of a new day won’t be able to take away? We learn nothing about her, besides she is hard-working and benevolent.

Fairing much worse despite his high-ranking presence in the Disney canon, is her Prince Charming, whose one moment of personality comes in him yawning at the ball. He’s handsome enough of a drawing, but what is it about Cinderella that draws him to her, aside from plot necessity? If Cinderella had spent half of the time engaging with its leads as it does with Gus, Lucifer, or Jacques, we’d have a much better film on our hands.

Most Disney films are only as good as their side-kicks and villain(s), and Cinderella only has half of that equation down. Lady Tremaine mostly stands around looking haughty, while Eleanor Audley’s delicious line readings do most of the major character building work. Audley would be much better served nine years later in Sleeping Beauty’s grand bitch supreme, Maleficent. And her two daughters aren’t much better, as they’re just loud, whiny brats with grand senses of entitlement. None of their scheming feels very pleasing in comparison to egotism evoked in, say, Ursula, Cruella, or the Evil Queen. In fact, given their lot in life and era in which their story takes place, the Lady’s gold-digging and scheming is almost understandable as a means for their survival.

Is Cinderella one of the best films in the Disney canon? No, but it’s not one of the worst, either. It’s serviceable, pleasing in its slight charms, but generally unsatisfactory. I consider it a warm-up for their eventual return to form in some of the later films of the Silver Era, a masterpiece like Sleeping Beauty needed something to pave the way. And Cinderella did bring in Mary Blair, whose concept art during this era is some of the greatest in the studio’s history. Her dreamy backgrounds and playful sense of color and dimension would find better use in Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland. It’s a good film, but nothing that enchants me quite as much as many of the other films I’ve mentioned in this review.

Cinderella

Posted : 9 years, 9 months ago on 9 September 2015 03:24

(A review of Cinderella)

Posted : 9 years, 9 months ago on 9 September 2015 03:24

(A review of Cinderella) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Man-Eater of Kumaon

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 1 September 2015 01:57

(A review of Man-Eater of Kumaon)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 1 September 2015 01:57

(A review of Man-Eater of Kumaon)I don’t think there’s any redeeming qualities about this disappointing film. This is a jungle adventure starring Sabu going up against man-eating tigers! At the very least, there should have been some major camp value to this thing, but there’s not. In fact, Sabu is barely a presence here, as the main star of the film is Wendell Corey as a disillusioned American doctor looking for meaning in India, during which time he overcomes his inherent racism and kills the titular jungle cat. That’s right, this is a movie in which a white hero goes into the jungle to learn about his place in the world through the lens of people of color, proving that he’s a better hero than these mystical-leaning hippies. Man-Eater of Kumaon is just too depressing to even talk about. The only half-way decent thing is the footage of the tiger stalking around the very fake jungle sets. If a few more coins had been spent to make those matte paintings and plywood sets more convincing, these sequences would have been elevated to the level of merely competent. This whole thing is a wash.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Tangier

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 31 August 2015 04:47

(A review of Tangier)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 31 August 2015 04:47

(A review of Tangier)Made on the demands of its star Maria Montez, Tangier is equivalent to those cheap discount versions of well-known films. You know the kind, they come out shortly before or after, go straight to DVD/home streaming, and have titles that are vaguely similar in hopes of tricking a susceptible viewer. For example, Transformers was a big hit, so, naturally, one of those bargain studios rushed out a film called Transmorphers. Tangier is basically that for Casablanca.

A rare black and white vehicle for Montez, Tangier tells a story of romance, intrigue, revenge, throws in a few musical breaks, and an exotic location to tie it all up. The actual plot is pretty simplistic: dancer wants revenge on diamond smuggling fascist who killed her family, teams-up with reporter looking to make it back to the big time. That’s it, and it’s not nearly interesting enough to sustain its brief 76 minutes.

The dialog is terrible, the acting approaching levels of camp or indifference (depending on who is in the part), and normally solid supporting players are left with nothing to do. Sabu and Louise Allbritton try valiantly to do something with their material, but they’re wasting their efforts here. Sabu’s warbling and awkward guitar playing of several well-known songs are worth a glance, if nothing else about his performance works.

The only reason to watch Tangier, aside from the unintentional camp, are the various costumes thrown upon Montez, and the lovely cinematography. Montez was a clotheshorse, not an actress. Her line readings are stiff and awkward, her facial expressions practically immobile, and she couldn’t project an emotion to save her life, but she looks great in the ornate costumes. The pageantry of them is astounding. It was clear that the film was trying to remake her image into that of Marlene Dietrich during her Josef Von Sternberg years, but Montez couldn’t project what Dietrich could, nor did she possess the concentrated bitchery or surprisingly tender moments.

The only other thing worth mentioning is the cinematography. It’s the kind of artful, beautiful series of images that classic films are built upon, yet it’s gone to waste on this trifle endeavor. If the film had a script half as solidly constructed as Casablanca, we’d be in better business. Tangier, if one is in the right mood, could be considered great for its camp value, but star Maria Montez holds no charm for me. I consider the whole thing a cheap piggy-backing on better known and beloved films.

A rare black and white vehicle for Montez, Tangier tells a story of romance, intrigue, revenge, throws in a few musical breaks, and an exotic location to tie it all up. The actual plot is pretty simplistic: dancer wants revenge on diamond smuggling fascist who killed her family, teams-up with reporter looking to make it back to the big time. That’s it, and it’s not nearly interesting enough to sustain its brief 76 minutes.

The dialog is terrible, the acting approaching levels of camp or indifference (depending on who is in the part), and normally solid supporting players are left with nothing to do. Sabu and Louise Allbritton try valiantly to do something with their material, but they’re wasting their efforts here. Sabu’s warbling and awkward guitar playing of several well-known songs are worth a glance, if nothing else about his performance works.

The only reason to watch Tangier, aside from the unintentional camp, are the various costumes thrown upon Montez, and the lovely cinematography. Montez was a clotheshorse, not an actress. Her line readings are stiff and awkward, her facial expressions practically immobile, and she couldn’t project an emotion to save her life, but she looks great in the ornate costumes. The pageantry of them is astounding. It was clear that the film was trying to remake her image into that of Marlene Dietrich during her Josef Von Sternberg years, but Montez couldn’t project what Dietrich could, nor did she possess the concentrated bitchery or surprisingly tender moments.

The only other thing worth mentioning is the cinematography. It’s the kind of artful, beautiful series of images that classic films are built upon, yet it’s gone to waste on this trifle endeavor. If the film had a script half as solidly constructed as Casablanca, we’d be in better business. Tangier, if one is in the right mood, could be considered great for its camp value, but star Maria Montez holds no charm for me. I consider the whole thing a cheap piggy-backing on better known and beloved films.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Cobra Woman

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 31 August 2015 04:47

(A review of Cobra Woman)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 31 August 2015 04:47

(A review of Cobra Woman)Lord, there’s good camp, there’s bad camp, and there’s camp that falls somewhere in-between. Cobra Woman falls into that middle ground for me. At times, it commits so completely to its ludicrous premise and scenarios that we reach a kind of Valhalla of knowingly terrible movie-making. Too often though, Cobra Woman is indifferent to its own strangeness, or plays it too seriously, or is just plain dull.

This is a large slice of cinematic ham. Between Maria Montez in a dual role (as both the good and bad twin sisters of an island kingdom), Sabu running around in tiny trunks, Lon Chaney Jr. trying to puff out his chest and suck in his gut as a deaf mute, and a few veteran actors earnestly trying to sell their bizarre dialog and characters, Cobra Woman has a certain amount of charm.

Montez isn’t much of an actress, but my god could she wear the most elaborate of clothing and sell it! The good sister gets stuck in dull swimwear and sarongs, while the bad girl gets the costumes dripping in jewels and covered in feathers. It’s like a drag queen’s wet dream. Just, for the love of God, don’t let her open her mouth and try to believably sell you on her characterization. Watch her for the glamour, and nothing more.

The rest of the film is made-up of a series of events that are either played up for their full ridiculous potential, or given-up on halfway through. An “elaborate” dance that Montez does to entice a cobra is a highlight. Her awkward body contortions and pointer-sister drag act is deliriously strange. Pity that the volcanic finale is such a bore. The cheapness isn’t embraced as it should be, and it becomes more distracting than anything else. The climatic payoff of the twin sisters isn’t very satisfying, and neither is the ending in which we abandon the island entirely. What was the point of the whole story if we’re just going to abandon the island after all of the trouble we went through on it? Cobra Woman is inept, but it has moments in which it grabs hold of its shaggy film-making and makes it worth watching, if for the unintended reasons.

This is a large slice of cinematic ham. Between Maria Montez in a dual role (as both the good and bad twin sisters of an island kingdom), Sabu running around in tiny trunks, Lon Chaney Jr. trying to puff out his chest and suck in his gut as a deaf mute, and a few veteran actors earnestly trying to sell their bizarre dialog and characters, Cobra Woman has a certain amount of charm.

Montez isn’t much of an actress, but my god could she wear the most elaborate of clothing and sell it! The good sister gets stuck in dull swimwear and sarongs, while the bad girl gets the costumes dripping in jewels and covered in feathers. It’s like a drag queen’s wet dream. Just, for the love of God, don’t let her open her mouth and try to believably sell you on her characterization. Watch her for the glamour, and nothing more.

The rest of the film is made-up of a series of events that are either played up for their full ridiculous potential, or given-up on halfway through. An “elaborate” dance that Montez does to entice a cobra is a highlight. Her awkward body contortions and pointer-sister drag act is deliriously strange. Pity that the volcanic finale is such a bore. The cheapness isn’t embraced as it should be, and it becomes more distracting than anything else. The climatic payoff of the twin sisters isn’t very satisfying, and neither is the ending in which we abandon the island entirely. What was the point of the whole story if we’re just going to abandon the island after all of the trouble we went through on it? Cobra Woman is inept, but it has moments in which it grabs hold of its shaggy film-making and makes it worth watching, if for the unintended reasons.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Arabian Nights

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of Arabian Nights)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of Arabian Nights)A near carbon copy of The Thief of Bagdad in tone and material, but without that film’s artistry and fantasy, Arabian Nights is Saturday matinee through-and-through, but a little too sluggish for its own good. Which isn’t to say that it’s bad, but it’s more half-formed. Too many characters get lost in the shuffle, or are brought in for easy name recognition but never paid off in a satisfactory way.

Arabian Nights is a grab-bag of elements, tossed together, and thrown in with low-comedy and high-production values. The story concerns two brothers (Leif Erickson and Jon Hall) warring over their kingdom, Scheherazade (Maria Montez), street magician and acrobat Ali Ben Ali (Sabu), Sinbad the Sailor (Shemp Howard), and Aladdin (John Qualen). The hodge-podge ensemble of characters from the tales never quite coheres, with Sinbad and Aladdin being prime opportunities for Universal to unleash it’s mega-budget and movie-magic on fantastical characters and special effects like they often did with their movie monsters, but forsaking that in favor of pratfalls and easy gags. It’s a missed opportunity.

Where Arabian Nights excels is in the production and costume designs, and its use of Technicolor. This is a movie drunk with bright, lurid colors. Each frame is a piece of pop art waiting to burst forth from the confines and assault our eyes. I mean that as a high compliment. The jewels sparkle, the various colors look like daydreams come to life, and the entire thing is remarkably well-preserved for a film of its age.

The sets and matte paintings create another imagine place, one in which a vast Arabian kingdom seems to have assembled itself from disparate parts of others. Numerous fairy tale films do this with their imagined European kingdoms, and this one is treated no differently. At times the multi-cultural cast seems a little lost, towered as they are above the vast production. Only Sabu seems comfortable in these settings, as Jon Hall is painfully generic, and Maria Montez is prone to somnambulistic vamping.

A little bit more fantasy would only have helped this film, but its minor escapist charm is pleasing enough. It knows it’s light-hearted, and plays to those strengths more often than not, but it still shows its age in many places. Too many of the supporting players feel like they’re reading off of cue cards, numerous nubile female players are offered up as cheesecake and nothing more, and two-thirds of the leads are a wash. It’s a very minor charmer, the kind of film you watched on a bored, rainy Sunday afternoon when nothing else is on.

Arabian Nights is a grab-bag of elements, tossed together, and thrown in with low-comedy and high-production values. The story concerns two brothers (Leif Erickson and Jon Hall) warring over their kingdom, Scheherazade (Maria Montez), street magician and acrobat Ali Ben Ali (Sabu), Sinbad the Sailor (Shemp Howard), and Aladdin (John Qualen). The hodge-podge ensemble of characters from the tales never quite coheres, with Sinbad and Aladdin being prime opportunities for Universal to unleash it’s mega-budget and movie-magic on fantastical characters and special effects like they often did with their movie monsters, but forsaking that in favor of pratfalls and easy gags. It’s a missed opportunity.

Where Arabian Nights excels is in the production and costume designs, and its use of Technicolor. This is a movie drunk with bright, lurid colors. Each frame is a piece of pop art waiting to burst forth from the confines and assault our eyes. I mean that as a high compliment. The jewels sparkle, the various colors look like daydreams come to life, and the entire thing is remarkably well-preserved for a film of its age.

The sets and matte paintings create another imagine place, one in which a vast Arabian kingdom seems to have assembled itself from disparate parts of others. Numerous fairy tale films do this with their imagined European kingdoms, and this one is treated no differently. At times the multi-cultural cast seems a little lost, towered as they are above the vast production. Only Sabu seems comfortable in these settings, as Jon Hall is painfully generic, and Maria Montez is prone to somnambulistic vamping.

A little bit more fantasy would only have helped this film, but its minor escapist charm is pleasing enough. It knows it’s light-hearted, and plays to those strengths more often than not, but it still shows its age in many places. Too many of the supporting players feel like they’re reading off of cue cards, numerous nubile female players are offered up as cheesecake and nothing more, and two-thirds of the leads are a wash. It’s a very minor charmer, the kind of film you watched on a bored, rainy Sunday afternoon when nothing else is on.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Jungle Book

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of The Jungle Book)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of The Jungle Book)After blowing fellow child actor, Desmond Tester, out of the water with his naturalism in stark contrast to Tester’s stage-bound acting techniques, Sabu went on to star in his two best feature films. 1940’s remake of The Thief of Bagdad’s success can’t be solely credited to him, but since so much of the film is spent with him, a good chunk of its eternal optimism, mischievous spirit, and fun-loving vibe can be. And those same attributes here in 1942’s Jungle Book, once again returning to the world of Rudyard Kipling to tackle the author’s most-beloved character, Mowgli, the final film in the Korda-Sabu pairing.

This film holds a tremendous amount of nostalgia for me. As a child, I probably watched this version more often than the famous Disney film. Something about this version just stayed with me more.

Perhaps it was the brightly colored sets? One of the great things about cinema is its ability to create fantastical, imagined lands out of real places. This India has little standing in reality, but it is a creation of a child’s imagination. This opulent, magical jungle is the type that the mind conjures up while reading an adventure story. Shot by W. Howard Greene and Lee Games, Jungle Book is a technical marvel. Its combination of matte paintings, real sets, and Technicolor vibrancy add up to something whimsical and daring. It’s a richly realized world, one that is easy to get lost in.

Or perhaps it was Sabu? Looking back on it, he was probably one of my earliest cinematic crushes. His lean muscular body on proud display, and a handsome face with full lips and big, bright eyes probably caused some deep stirrings in my boyhood that I didn’t understand until later. His acting has also improved by this time, essaying the change from feral wild child to uneasily domesticated youth with ease and consummate skill. Sabu’s athleticism and charisma matured as he was, with this film being the perfect template for his particular brand of star persona.

Maybe it was all of the animals, both real and animatronic? Among the opulent sets are several engaging sequences in which trained animals are let loose. Granted, certain ones are entirely fake, both by design of the screenplay and by how dangerous the actual creatures were. Baloo the bear, Bagheera the panther, Raksha and Father Wolf, Shere Khan the tiger, and the various monkeys and deer are all live animals. They are anthropomorphized to a point, but nowhere near the way that they would become in Disney’s version. We’re told Mowgli can talk to the animals, and as the film progresses we begin to hear their voices. Mainly, two snake characters, the python Kaa and the old cobra Nag, are fakeries and heavy talkers.

For obvious reasons, these two characters are large rubber creatures. There’s something charming and quaint about these obviously artificial snakes. It adds to the mystique and fantasy of the film, in much the same way the dinosaurs do in King Kong. These are not real creatures, but imagined approximations of those creatures. While a dastardly effete villain in Disney’s version, Kaa is one of Mowgli’s trusted allies here. While Nag warns him of the dangers of the treasure he guards, giving Mowgli a talk about the destructive powers of man’s greed.

If Jungle Book has a flaw, it’s the third act which stretches on just a few minutes too long. I think shaving about ten minutes from this final section would have tightened up the pace. After ripping through at great speed and clarity through the various other adventures, our focus is pulled away from Mowgli for too long here, and we realize just how titanic Sabu was to making this entire enterprise work so smoothly.

Granted, the finale takes place in the beautifully wrought decaying ruins of a maharaja’s palace, so even if the pace is too slowly there’s still something beautiful to look at. Even better is the fiery scenes in which Mowgli eventually rejects “man’s world” and returns to the jungle. Mainly a grand spectacle, which is not a knock against the movie, Jungle Book is the kind of fine entertainment that rarely gets made anymore. I was only too happy to discover that the nostalgic glow this movie possessed in my memory was well-served. It is one that we should cherish.

This film holds a tremendous amount of nostalgia for me. As a child, I probably watched this version more often than the famous Disney film. Something about this version just stayed with me more.

Perhaps it was the brightly colored sets? One of the great things about cinema is its ability to create fantastical, imagined lands out of real places. This India has little standing in reality, but it is a creation of a child’s imagination. This opulent, magical jungle is the type that the mind conjures up while reading an adventure story. Shot by W. Howard Greene and Lee Games, Jungle Book is a technical marvel. Its combination of matte paintings, real sets, and Technicolor vibrancy add up to something whimsical and daring. It’s a richly realized world, one that is easy to get lost in.

Or perhaps it was Sabu? Looking back on it, he was probably one of my earliest cinematic crushes. His lean muscular body on proud display, and a handsome face with full lips and big, bright eyes probably caused some deep stirrings in my boyhood that I didn’t understand until later. His acting has also improved by this time, essaying the change from feral wild child to uneasily domesticated youth with ease and consummate skill. Sabu’s athleticism and charisma matured as he was, with this film being the perfect template for his particular brand of star persona.

Maybe it was all of the animals, both real and animatronic? Among the opulent sets are several engaging sequences in which trained animals are let loose. Granted, certain ones are entirely fake, both by design of the screenplay and by how dangerous the actual creatures were. Baloo the bear, Bagheera the panther, Raksha and Father Wolf, Shere Khan the tiger, and the various monkeys and deer are all live animals. They are anthropomorphized to a point, but nowhere near the way that they would become in Disney’s version. We’re told Mowgli can talk to the animals, and as the film progresses we begin to hear their voices. Mainly, two snake characters, the python Kaa and the old cobra Nag, are fakeries and heavy talkers.

For obvious reasons, these two characters are large rubber creatures. There’s something charming and quaint about these obviously artificial snakes. It adds to the mystique and fantasy of the film, in much the same way the dinosaurs do in King Kong. These are not real creatures, but imagined approximations of those creatures. While a dastardly effete villain in Disney’s version, Kaa is one of Mowgli’s trusted allies here. While Nag warns him of the dangers of the treasure he guards, giving Mowgli a talk about the destructive powers of man’s greed.

If Jungle Book has a flaw, it’s the third act which stretches on just a few minutes too long. I think shaving about ten minutes from this final section would have tightened up the pace. After ripping through at great speed and clarity through the various other adventures, our focus is pulled away from Mowgli for too long here, and we realize just how titanic Sabu was to making this entire enterprise work so smoothly.

Granted, the finale takes place in the beautifully wrought decaying ruins of a maharaja’s palace, so even if the pace is too slowly there’s still something beautiful to look at. Even better is the fiery scenes in which Mowgli eventually rejects “man’s world” and returns to the jungle. Mainly a grand spectacle, which is not a knock against the movie, Jungle Book is the kind of fine entertainment that rarely gets made anymore. I was only too happy to discover that the nostalgic glow this movie possessed in my memory was well-served. It is one that we should cherish.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

The Drum

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of The Drum)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of The Drum)After the enormous success of Elephant Boy, producer Alexander Korda signed Sabu to an exclusive contract, smart move, and rushed this film into production, which was maybe a little too rushed. The Drum is the first film to give Sabu above the title billing, but he’s really more of a featured player in an awkward piece of British propaganda. It has its moments, but a nasty aftertaste of pro-colonialism ultimately sinks it.

The Drum, or Drums as it was released in the U.S., tells the story of a brewing uprising between two sides of an Indian family. On one side, Prince Azim (Sabu) who favors the British, and is a smiling, happy-go-lucky example of the colonized, while his uncle, Prince Ghul (Raymond Massey, in brownface), wants to kick the British out. Despite Sabu’s once-again winning presence and charming performance, my sympathies couldn’t help but lie with his uncle.

Despite being routinely asked to side with the pro-Empire side of the equation, I kept thinking about how the riotous fury of Pince Ghul and his followers was understandable, more empathetic and sympathetic than the questionable material you heard coming out of Sabu’s mouth. I don’t blame him, he was only a thirteen-year-old. Later films would drop this political baggage and go back to the fantastical, thankfully.

The Drum does have a few bright spots. Ignoring the ugly realities of white actors done up as people of color, Massey’s performance is another hissable and enjoyable turn from an actor who excelled at playing devious characters. Roger Livesey’s a smart, dashing hero in the central role, and Valerie Hobson is warm and nurturing as his wife. The action scenes are daring, and moments of suspense are well-made. The cinematography, once the crown jewel of the film, looks like it was once impressive, but the time and care has not gone into properly restoring it. What remains looks great, but I wonder how much better it could be if someone had taken the time to restore it to its proper magnificence.

In all, The Drum has individual parts that work exceptionally well, they’re just in service of a whole that is questionable. No, it’s not questionable. It’s just ugly, a bitter “Sun Never Sets” fantasy wrapped up in a pretty candy coating. Sabu deserved better treatment than this. It’s no surprise to me to learn that audiences in India reacted violently to this film’s politics. I don’t blame them.

The Drum, or Drums as it was released in the U.S., tells the story of a brewing uprising between two sides of an Indian family. On one side, Prince Azim (Sabu) who favors the British, and is a smiling, happy-go-lucky example of the colonized, while his uncle, Prince Ghul (Raymond Massey, in brownface), wants to kick the British out. Despite Sabu’s once-again winning presence and charming performance, my sympathies couldn’t help but lie with his uncle.

Despite being routinely asked to side with the pro-Empire side of the equation, I kept thinking about how the riotous fury of Pince Ghul and his followers was understandable, more empathetic and sympathetic than the questionable material you heard coming out of Sabu’s mouth. I don’t blame him, he was only a thirteen-year-old. Later films would drop this political baggage and go back to the fantastical, thankfully.

The Drum does have a few bright spots. Ignoring the ugly realities of white actors done up as people of color, Massey’s performance is another hissable and enjoyable turn from an actor who excelled at playing devious characters. Roger Livesey’s a smart, dashing hero in the central role, and Valerie Hobson is warm and nurturing as his wife. The action scenes are daring, and moments of suspense are well-made. The cinematography, once the crown jewel of the film, looks like it was once impressive, but the time and care has not gone into properly restoring it. What remains looks great, but I wonder how much better it could be if someone had taken the time to restore it to its proper magnificence.

In all, The Drum has individual parts that work exceptionally well, they’re just in service of a whole that is questionable. No, it’s not questionable. It’s just ugly, a bitter “Sun Never Sets” fantasy wrapped up in a pretty candy coating. Sabu deserved better treatment than this. It’s no surprise to me to learn that audiences in India reacted violently to this film’s politics. I don’t blame them.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Elephant Boy

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of Elephant Boy)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 17 August 2015 09:23

(A review of Elephant Boy)Lots of actors make debut film appearances with roles that perfectly match their skills and charisma, but Sabu’s role here is a piece of alchemy and serendipity captured on camera. Inspired by Rudyard Kipling’s “Toomai of the Elephants,” one of the many stories in the Jungle Books, Elephant Boy provides Sabu with the first of his enjoyable, charming adventure stories.

Elephant Boy tells the story of Toomai, a ten-year orphan who dreams of becoming an elephant-handler, but is told this dream will not come to pass until he sees the elephant’s dancing. As luck would have it, while looking for a child to play the title role, producer Alexander Korda and director Robert Flaherty found Sabu, the son of an elephant-handler.

In many ways, the story of Elephant Boy is reflective of Sabu’s own journey to international movie stardom. Sabu’s mother died while he was young, his father passed away a short time before being discovered, but all of the stuns and tricks that Sabu performs with the elephants in the film are real. If you switched out Toomai’s dream of becoming a respected mahout (what the Indian’s call an elephant driver) for international movie-stardom, you’d have the exact same story reflecting back and forth between character and actor.

Elephant Boy is not a perfect film, as the two directors and their respective directions often times come into awkward dramatic conflict. Zoltan Korda was hired to direct the dramatic tissue connection the various location-specific footage of animals in the wild shot by Flaherty. The film needs a strong center to hold it all together, and Sabu provides this in spades.

His naturalism before the camera makes some of the stiff, affected line deliveries of the various British cast members appear more tin-eared and false than before. Naturally exuberant, Sabu’s sense of fun and adventure is infectious. His joyous nature and mega-watt charisma begin to overtake you as the film goes on. He elevates the entire thing by his sheer strength, even if his phonetically learned English is often times shaky.

In the end, Elephant Boy may be slight, but it’s a rousing adventure story nonetheless. The best moments are ones in which the narrative takes a backseat to enjoying the moment. The relationship between Sabu and the elephant is a unique spin on the boy-and-his-dog narratives of other films. And the various bits of animal footage is wondrous to watch, it might not add anything of importance to the plot, but the gives the film a sense of truth in location and narrative that is important. After watching this thoroughly enjoyable Saturday matinee adventure, it’s very easy to see why Sabu would go on to become on the strangest, but most charismatic of movie stars in the forties.

Elephant Boy tells the story of Toomai, a ten-year orphan who dreams of becoming an elephant-handler, but is told this dream will not come to pass until he sees the elephant’s dancing. As luck would have it, while looking for a child to play the title role, producer Alexander Korda and director Robert Flaherty found Sabu, the son of an elephant-handler.

In many ways, the story of Elephant Boy is reflective of Sabu’s own journey to international movie stardom. Sabu’s mother died while he was young, his father passed away a short time before being discovered, but all of the stuns and tricks that Sabu performs with the elephants in the film are real. If you switched out Toomai’s dream of becoming a respected mahout (what the Indian’s call an elephant driver) for international movie-stardom, you’d have the exact same story reflecting back and forth between character and actor.

Elephant Boy is not a perfect film, as the two directors and their respective directions often times come into awkward dramatic conflict. Zoltan Korda was hired to direct the dramatic tissue connection the various location-specific footage of animals in the wild shot by Flaherty. The film needs a strong center to hold it all together, and Sabu provides this in spades.

His naturalism before the camera makes some of the stiff, affected line deliveries of the various British cast members appear more tin-eared and false than before. Naturally exuberant, Sabu’s sense of fun and adventure is infectious. His joyous nature and mega-watt charisma begin to overtake you as the film goes on. He elevates the entire thing by his sheer strength, even if his phonetically learned English is often times shaky.

In the end, Elephant Boy may be slight, but it’s a rousing adventure story nonetheless. The best moments are ones in which the narrative takes a backseat to enjoying the moment. The relationship between Sabu and the elephant is a unique spin on the boy-and-his-dog narratives of other films. And the various bits of animal footage is wondrous to watch, it might not add anything of importance to the plot, but the gives the film a sense of truth in location and narrative that is important. After watching this thoroughly enjoyable Saturday matinee adventure, it’s very easy to see why Sabu would go on to become on the strangest, but most charismatic of movie stars in the forties.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Heartburn

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 14 August 2015 04:59

(A review of Heartburn)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 14 August 2015 04:59

(A review of Heartburn)Perhaps my expectations were too high, but a film combining the talents of Meryl Streep, Jack Nicholson, and Mike Nichols should not be this flabby and shapeless. Heartburn begins with a good foundation, but quickly crumbles once we realize it’s main character is going to project all of the blame for the failed relationship on her partner, and scene after scene will not add up to a satisfying conclusion.

Perhaps the fault of this lies squarely at the foot of Nora Ephron, who wrote the screenplay based upon her thinly disguised autobiographical novel. There’s never any believable or reasonable explanation for these two characters to attract each other, marry, or continually orbit each other’s lives. The script also begins to unravel as an episodic structure develops and we quickly realize that these scenes are not going to build upon each other into a coherent narrative. This rambling, shaggy structure works fine for a novel in which slices of life moments can reveal character depths or inner monologues, but that freewheeling structure is hard to translate to film. A tighter control is needed to wrangle all of the moving parts into a whole that feels complete. Heartburn doesn’t have that guiding hand.

While Streep and Nichols typically work magic together, and present her with a flawed, interesting character, too many of the other actors are wasted. Nicholson is stuck with a thinly drawn figure, one that we’re supposed to hiss at more than we understand. Consistently strong supporting players like Maureen Stapleton and Catherine O’Hara are given roles that look like plum parts before eventually just disappearing. They do solid work with what little they’re given to do, but this is mostly a film for Streep to suffer, cry, fall into anxious fits, regain strength, then shove a pie in her husband’s face. It’s not a very exciting film, and I only watched it as a major fan of Nichols, Nicholson, and Streep. Unless you're also a major fan of those three, I don’t really know if I can recommend giving this one a spin.

Perhaps the fault of this lies squarely at the foot of Nora Ephron, who wrote the screenplay based upon her thinly disguised autobiographical novel. There’s never any believable or reasonable explanation for these two characters to attract each other, marry, or continually orbit each other’s lives. The script also begins to unravel as an episodic structure develops and we quickly realize that these scenes are not going to build upon each other into a coherent narrative. This rambling, shaggy structure works fine for a novel in which slices of life moments can reveal character depths or inner monologues, but that freewheeling structure is hard to translate to film. A tighter control is needed to wrangle all of the moving parts into a whole that feels complete. Heartburn doesn’t have that guiding hand.

While Streep and Nichols typically work magic together, and present her with a flawed, interesting character, too many of the other actors are wasted. Nicholson is stuck with a thinly drawn figure, one that we’re supposed to hiss at more than we understand. Consistently strong supporting players like Maureen Stapleton and Catherine O’Hara are given roles that look like plum parts before eventually just disappearing. They do solid work with what little they’re given to do, but this is mostly a film for Streep to suffer, cry, fall into anxious fits, regain strength, then shove a pie in her husband’s face. It’s not a very exciting film, and I only watched it as a major fan of Nichols, Nicholson, and Streep. Unless you're also a major fan of those three, I don’t really know if I can recommend giving this one a spin.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

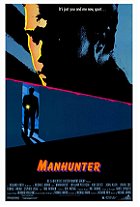

Manhunter

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 14 August 2015 04:59

(A review of Manhunter)

Posted : 9 years, 10 months ago on 14 August 2015 04:59

(A review of Manhunter)Including the current television series (which if you never watched it, how dare you), Hannibal Lecter has appeared in a (loose) franchise with 6 distinct entries. The television series, Hannibal, may be the most artistically daring and original of the various works, but Manhunter was a clear and obvious influence. Based upon Red Dragon, the first of Thomas Harris’ novels to use Lector, Manhunter is also the second-best of the five films. (Sorry, but The Silence of the Lambs is just a magnificent piece of pop-thriller film-making.)

On its own merits, Manhunter is one hell of a film. With a serial killer, dubbed The Tooth Fairy but preferring to call himself the Great Red Dragon over his obsession with that painting, targeting happy families, Will Graham is called back into the FBI. Graham had previously captured Hannibal Lecter (called Lector here, for some reason), and he uses that infamous killer as a springboard to find the Tooth Fairy, a killer with seemingly no clues or traces of where to find him. Graham’s strong sense of empathy allows for him to enter the minds of killers, to figure out their tactics and motivations, to work from the inside out to find them.

All of this is old hat if you’ve seen Brett Ratner’s Red Dragon, or you’ve been watching the television show. No matter, Manhunter, despite being roughly thirty years old, is still a refreshing spin on the material. Director Michael Mann’s clinical detachment, tight sense of framing, and expressionist use of color suites the material just fine. The very 80s shine is all surface level, and it isn’t long until we’re descending into more shadows and use of light to evoke mood and tension.

Harris’ purple prose and melodramatic narrative twists are underplayed by all involved, making the action seem, somehow, real and true. William Petersen’s Will Graham has a clear descent into near-madness to play. Petersen’s handsome face slowly drains itself of life and energy, most of this is accomplished with just his eyes. By the end, he’s wearing a haunted look that makes one question if he can return to some semblance of normalcy after staring into the abyss for so long.

Brian Cox’s portrayal of Lector is an interesting departure from the more polite, if uneasy Anthony Hopkins, and the faux-gallantry and tortured poet of Mads Mikkelsen. Cox chooses to play his Lecter as the physical embodiment of intellect gone evil. He’s a series of wild eye flashes and honey-voiced threats, but this Lecter isn’t in it enough to leave a more impressionable mark. Perhaps a fault of the script, or perhaps an artistic choice, but it seems odd to deny us one of the most dastardly charismatic parts of the story for so much of the running time. Tom Noonan is much better as the Tooth Fairy, a character we almost feel some sympathy for in his inability to relate to his fellow man, but not enough to make us forget about the horrific crimes he’s routinely committing. His physicality alone is imposing and distressing, and once we get to a scene where he tortures and kills a journalist, any positive feelings towards the character have long evaporated into a sense of dread and fear.

If Manhunter has any problem, and it wasn’t one for me, it’s that the entire thing feels artificial, fussily designed and staged. This tilts the dramatics more towards the abstract, teetering on the brink of hallucinatory nightmare images dancing before our eyes. This is purposefully remote and icy, not the funeral dirge and without the sense of repeated trauma of The Silence of the Lambs, Manhunter is but another option in adapting the source material. I think it’s underrated and undervalued as a film, and I can see its influence in films like Seven.

On its own merits, Manhunter is one hell of a film. With a serial killer, dubbed The Tooth Fairy but preferring to call himself the Great Red Dragon over his obsession with that painting, targeting happy families, Will Graham is called back into the FBI. Graham had previously captured Hannibal Lecter (called Lector here, for some reason), and he uses that infamous killer as a springboard to find the Tooth Fairy, a killer with seemingly no clues or traces of where to find him. Graham’s strong sense of empathy allows for him to enter the minds of killers, to figure out their tactics and motivations, to work from the inside out to find them.

All of this is old hat if you’ve seen Brett Ratner’s Red Dragon, or you’ve been watching the television show. No matter, Manhunter, despite being roughly thirty years old, is still a refreshing spin on the material. Director Michael Mann’s clinical detachment, tight sense of framing, and expressionist use of color suites the material just fine. The very 80s shine is all surface level, and it isn’t long until we’re descending into more shadows and use of light to evoke mood and tension.

Harris’ purple prose and melodramatic narrative twists are underplayed by all involved, making the action seem, somehow, real and true. William Petersen’s Will Graham has a clear descent into near-madness to play. Petersen’s handsome face slowly drains itself of life and energy, most of this is accomplished with just his eyes. By the end, he’s wearing a haunted look that makes one question if he can return to some semblance of normalcy after staring into the abyss for so long.

Brian Cox’s portrayal of Lector is an interesting departure from the more polite, if uneasy Anthony Hopkins, and the faux-gallantry and tortured poet of Mads Mikkelsen. Cox chooses to play his Lecter as the physical embodiment of intellect gone evil. He’s a series of wild eye flashes and honey-voiced threats, but this Lecter isn’t in it enough to leave a more impressionable mark. Perhaps a fault of the script, or perhaps an artistic choice, but it seems odd to deny us one of the most dastardly charismatic parts of the story for so much of the running time. Tom Noonan is much better as the Tooth Fairy, a character we almost feel some sympathy for in his inability to relate to his fellow man, but not enough to make us forget about the horrific crimes he’s routinely committing. His physicality alone is imposing and distressing, and once we get to a scene where he tortures and kills a journalist, any positive feelings towards the character have long evaporated into a sense of dread and fear.

If Manhunter has any problem, and it wasn’t one for me, it’s that the entire thing feels artificial, fussily designed and staged. This tilts the dramatics more towards the abstract, teetering on the brink of hallucinatory nightmare images dancing before our eyes. This is purposefully remote and icy, not the funeral dirge and without the sense of repeated trauma of The Silence of the Lambs, Manhunter is but another option in adapting the source material. I think it’s underrated and undervalued as a film, and I can see its influence in films like Seven.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Login

Login

Home

Home 95 Lists

95 Lists 1531 Reviews

1531 Reviews Collections

Collections